Video Feature & Web-Exclusive Interview

Musician: TIM O’BRIEN

Performers: Tim O’Brien & Jan Fabricius

Songwriter: Bill Withers

Tim O’Brien is a well-respected Grammy Award-winning musician and songwriter who can weave a tale with his intricate style of playing a wide variety of instruments, including guitars, fiddles and mandolins.

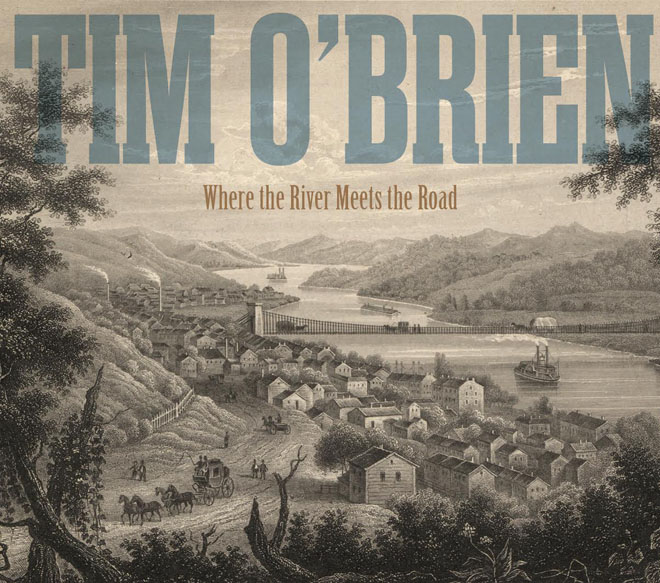

Where the River Meets the Road, released in the spring of 2017, celebrates the music of O’Brien’s native state—West Virginia. After 15 solo records and a myriad of collaborations, he looks back at some early influences.

This collection mixes bluegrass, country, old-time and Americana with songs from O’Brien and other West Virginia natives—Bill Withers, Hazel Dickens and Billy Edd Wheeler, among others. Guests on the recording include country artists Chris Stapleton and Kathy Mattea, as well as bluegrass instrumentalists Stuart Duncan and Noam Pikelny.

The title track tells the story of Tim’s great grandfather, who in 1851 emigrated from Ireland to Wheeling, West Virginia. Back then, the new National Road had just connected Baltimore and the east coast to the Ohio River—and Wheeling was Where the River Meets the Road. The cover image is an engraving from that time, showing what young Thomas O’Brien would have seen as he completed his journey.

Mmusicmag.com is proud to premiere O’Brien’s take on Bill Withers’ “Grandma’s Hands.” We talked with Tim O’Brien about his creative inspiration and songwriting, his passion for music, and what keeps him writing songs and playing music.

TIM O’BRIEN Web-Exclusive Interview

with M Music & Musicians magazine publisher, Merlin David

Who inspired you to write songs?

I was under the spell of the Beatles and Roger Miller—that’s five good songwriters right there. (Laughs) I like to write little stories and make stuff up. I like poetry, and rhyming it for fun. When I started playing guitar, it was a natural thing to attempt to write songs. Within a year or two, when I was 13 or 14, I started writing songs. I didn’t really apply myself until I was going to make some recordings with Hot Rize. We decided we needed songs—something that no one else has.

Tell us about the early years.

My sister and I would sing. We played little school shows. When I was 15 or 16, I was in a band. The other guys wrote, so I’m not sure they did any of my songs. I had a reel-to-reel, but I don’t remember recording my songs on it. But when cassettes came, I started recording songs on them. It didn’t seem like it was anything serious, yet it was very natural.

Tell us about those first songs you wrote.

Around 13 or 14 years of age, I was involved with Folk Mass. All Christian religions had them, and so did the Catholic Church. We’d play guitars and sing new songs. We had writers that were servicing this new thing—when the Pope and Vatican said you can have Mass in your own language. A lot of lyrical content in Latin got thrown away. They just wanted new music. The kids who were playing guitars got drafted into playing an A-minor chord and having everybody sing. (Laughs) I was one of them. Actually, as we started, there were about half-a-dozen guitars in the front row of the church. Then, over a couple of years, it dwindled down to just—me.

Did you write these songs?

The young priest is the one that brought this change in our church. A woman who was in the Lay Society (the Nun religious order that supports the church)—wanted to write music for church services. She and the priest would look at Scripture and she’d say, “You know, if we just changed this word into more modern language, we’ll get the same meaning.” I was there to be the musical writer. I was into Joni Mitchell and I had my guitar in different tunings. I’d play around until it fit the words. It’s funny because a couple of them ended up being regular songs in church. “Look at the birds of the air…”—a famous passage in the New Testament. That was one that got a lot of play. (Laughs) But that was just in my parish in Wheeling, West Virginia—in the northern panhandle of the state.

What initially made you want to write songs?

From the beginning, I seemed to have an aptitude for music. As an adolescent, I wasn’t great at sports. I liked some sports, but I wasn’t a great team sports player. Music was something of value that I could do on my own. It fed the fire of self-esteem. I did a tiny bit of acting, but writing in school dovetailed with music. I didn’t know if music would be my livelihood, but I wanted to try the various parts of it. I did teach myself to read music. I wanted to diversify to see what else was out there.

When did you take songwriter more seriously?

It looked like Hot Rize could get a recording contract in the late 70s with a relatively new Rounder Records. Pete [Wernick] had already recorded with Country Cooking. It seemed like we could make a record if we just got some material together. We felt it would help to write in the genre. We wanted to play traditional bluegrass. We didn’t know how. We did our best and it ended up being a little different version of it—and it was well received.

When did others start covering your song?

About 10 years in, Kathy Mattea had recorded three of my songs. Then I realized I was not only making money and adding value to my band’s resume, but there was money coming in the mailbox. I figured I should pay more attention to that if I wanted to make a living and raise some kids. I guess it was an economic thing. (Laughs) Expediency and economics drove it. But I do like the process. I feel it’s like a puzzle that you get to solve, and I get excited when I feel like I’m solving the puzzle—to put something down with words and music that works.

Which was your biggest hit with Kathy Mattea?

“Untold Stories” went up to #4 on Billboard. But “Walk the Way the Wind Blows” was the first one—and the title of that album—and it was her second radio hit. It was crucial to her. Then all of a sudden I’ve got a little bit of a track record with her, and she follows up with another one about a year later with “Untold Stories.” That put me on the map as a writer. People started asking for songs, and I kept thinking—geez, I don’t even write that many songs. (Laughs) Maybe I should write more.

How did the idea of “Untold Stories” come to you?

My cousin, Sony Ames, was a career classical musician—a percussionist with the National Symphony. My father was his uncle and also his godfather. They had a disagreement over whether the Vietnam War was legit. My cousin was totally against it, and my father found it troubling. There’s more—it’s a long story, but that’s all I’ll say. Meanwhile my brother, who was his contemporary, enlisted in the Marines—and died in Vietnam. My cousin and my father were estranged for years. He’s the only other professional musician other than my sister and me. I always looked up to him because he left and became a musician. He left home when I was only 10 years old. I got to know him as an adult and he told me this story of their estrangement—and how they made up years later. Basically it was—let’s let bygones be bygones. These were the untold stores. The song wrote itself real fast. It sounds like a love song, and it is. It’s just a love song between an uncle and his nephew. I had never known any of that until I was around 25 years old. Then, I got to sing it for my cousin and my dad. (Laughs)

Did you ever think it would be covered—and be a hit?

No. I didn’t think so. I just liked the song. It was a networking thing. I got to know Kathy Mattea because her manager shared offices with Hot Rize’s agent. One day, I saw her promo CDs on a shelf, and the guy said, “Hey, take one. She’s from West Virginia too.” Then we met. And she did the same thing—one day she got my record at the office. Then we sang together on Mountain Stage. Later, when she got a song that she liked, and saw that I wrote it—it kinda helped. It might have made the difference—the straw that pushed it into happening. It was pretty well played in the summer of ’89—and went to #4.

What did you learn about yourself back then?

As a musician, you’re not only trying to connect with your audience, but also with other musicians. I was always told to get together with people who are just a little bit better than you, and you’ll learn more when you collaborate with them. Kathy had a lot more muscle behind her. When they need what you do—as a musician, singer and songwriter, then you cultivate those relationships, and both of you can go further. It worked well.

Have you worked with her lately?

I’m actually producing a record of hers right now. It’s interesting because it’s full circle. She still plays a lot of shows with just a guitar player and her—and we started the album that way, but we’ve added to it. She’s not pandering to country radio. She’s on her own and has a strong following. She’s able to just express herself, and it’s pretty cool.

Are there any challenges?

As you go on, it gets harder to make a new record. If you’ve had a lot of success, you have a tendency to be intimidated by that. I found it hard to make a Hot Rize record several years ago—after 25 years of sitting dormant. Expectations are inflated unnaturally. When we made those records, we kept thinking—wish we could have done better. Now people are saying—we love those records, can you make more of those? (Laughs) The main thing is that you have to listen to yourself. That’s where you start, that’s what you come back to—and that’s what’s important.

Tell us about the West Virginia Hall of Fame.

I’ve been involved with the West Virginia Music Hall of Fame for the past dozen years. Michael Lipton, who started it, is the band leader on the Mountain Stage radio show. He and Andy Ridenour, who produces the shows, decided to start this Hall of Fame in West Virginia. They asked me to be on the Board. I agreed, and right off the bat we made a record—Always Lift Him Up: A Tribute to Blind Alfred Reed. I didn’t know much about his songs other than “How Can a Poor Man Stand Such Times and Live?” Then we wanted to get Little Jimmy Dickens to sing a song, and Connie Smith, and Kathy Mattea.

Photo credit Scott Simontacchi

Honoring these musicians must be satisfying.

You get to meet the people, and they get inducted. It brought me back home to where I started, and it forced me to learn things that I hadn’t learned—about where I’m from, and where the music’s from—and who these musicians are. You learn about all the different genres. Johnnie Johnson from Fairmont, West Virginia, who played with Chuck Berry—they wrote Johnny B. Goode about him. He’s a cowriter with Chuck Berry. And George Crumb is an incredible modern classical composer—opera singer. And the guy who wrote “Sweet Georgia Brown” comes out of the coal fields—a Black man named Maceo Pinkard. It just gets real interesting. So, I guess I’m focusing on where I came from.

How did this new album Where the River Meets the Road evolve?

I knew I was going to make this project, and I wanted something original, so I wrote two songs. I guess it could have written more. I wrote one about my great grandfather and how he came from Ireland and ended up in West Virginia—that’s the title track. Then I wrote one about my own childhood, “Guardian Angel.” I knew some of the songs already, like “High Flying Bird.” But I knew them more in the back of my mind. I hadn’t really sung them before. For West Virginia, this song is sort of the linchpin—the crystal around which it forms. The song talks about a guy like me, when I was 15 or 16 wanting to get the heck away from West Virginia, get away from your parents and go on your own. I wanted to get far away. I ended up going out to Colorado. This song from West Virginia by Billy Edd Wheeler seemed perfect for me. I got to meet one of the Bailes Brothers when they got inducted into the Hall of Fame, and played mandolin behind him. Same with Hazel Dickens. I think I sang a Jimmy Dickens song at the induction ceremony. It all came to the forefront.

Especially in these times, do you think it’s important to write songs with social significance—songs that have greater meaning?

If you want to make a statement with music—you want to be yourself. You know John Hartford said: don’t get famous for something you don’t like doing—that’s really good advice. If you believe in something, and you are an artist—that’s more than half of our lives. Who we are and what we’re doing—it defines us. It’s only natural that a social viewpoint will surface in your music. I like it best when it’s indirect, but every once in a while you have to call a spade a spade. (Laughs)

Tell us about one of those songs you’ve written.

Someone came to a show at Wolf Trap Barns and handed me this New Yorker article about a chemical spill in Charleston, West Virginia that shot out the water supply for about three or four months. I already get that magazine, but I knew I had to read it and study it. She said, “Somebody needs to write music about this.” So I wrote a song, and made it humorous—it’s called “Brush My Teeth with Coca Cola.” I don’t sing it too much, but I think I need to bring it back because clean water is still on people’s minds. I’m not really the best at writing that stuff. I’ve got some songs that I’ve only sung maybe once—“Pussy Hat.” (Laughs) I mostly want to bring people together rather than tear them apart. I really admire Steve Earle. He mostly preaches to the choir, yet he has enough of a voice. Like his song about John Walker Lindh—people were really interested, and it caused dialogue. That was good. I’ve been singing “Pastures of Plenty” more often—because of DACA.

How do you deal with fans who might view things differently?

Right after the Las Vegas massacre, I did a recent Facebook post about the NRA. Rosanne Cash, in her editorial today said people will boo you, they will do this or do that. We had death threats. But nobody is going to bother me. My audience knows who I am. It was funny when people burned records. All these new fans came along who said—I didn’t know about the Dixie Chicks but I like them now. (Laughs) It can happen the other way around—and you can get more fans. In my case, I just don’t think I have anything to fear—so I speak my mind. If I don’t write social commentary, it’s not because I’m afraid of it—it’s just that I haven’t figured out the right way of saying it.

How do you view your music?

My pursuit with music is to get people to take time out of their day to get their minds to wander and think about important things in life. They put the mundane and the deadlines aside for an hour-and-a-half concert—very similar to going to church. They still have their hassles but at least they can sit down for a while and say, “OK. Let’s just love each other and let’s see what we can do to get through this.” It gives them a license to slow down and contemplate. That’s the value. As a musician, the best thing I can do is to give people a chance to just allow them to let their minds focus on their situation in life—beyond the next thing they have to do.

What songwriting tip would you like to offer?

What I do is random. I write notes in books, and I save all the notebooks, but I hardly ever look at them. Usually the things that are going to drive me to write and finish a song—they don’t leave me alone—they’re in my head. I’m always looking for a way into a song. Sometimes it’ll take years before the topic I had in my mind unlocks. It’s usually a little phrase. So I look for these little phrases and it clicks. If I think a phrase might unlock, I’ll write that. Sometimes I’ll save news clippings and articles or books. I tried to do The Artist’s Way workshop thing. I didn’t quite succeed. (Laughs) But I know journaling is good. Making a regular place to do it is good. It’s mysterious. What’s great is everybody has their own way. I think everybody can be an artist, if they wanted to be. Creating something is therapeutic. Everybody has a different thing to offer. As a result, there really are no rules. It’s however you can get at it.

What instrument/equipment can you not live without?

I have Piezo pickups and mini-mics on all my instruments. I’ve used various blenders over the years—they seem to always go out of production. (Laughs) What I’m using now is the latest thing that went out of production—the Seymour Duncan D-TAR. It’s a stereo preamp where you can adjust one side or the other—and balance them. I like the flexibility of it, and it makes a big difference—it’s very handy. You can go only to the pickup or only to the mic, or a combo. But pickup technology seems to improve so much, and maybe there’s something else out there.

It just helps my confidence to know I’m giving the sound guy a decent sounding signal.

Photo credit Scott Simontacchi

How do you maintain your instruments?

I just keep the instruments in good shape. You need to take time to do that because they can wear out. I play 100+ shows a year, so the frets wear out. You have to clean them up—clean up the fingerboard—set-up the action. And with the fiddle it’s always about adjusting the sound post— and the bridge can warp. You gotta keep it in great shape. Most people have a guitar and only play it a little each evening. They’re not relying on it. As a professional, it’s like having a car that you rely on—that you need to get to work in. You need to keep it maintained.

You have so many instruments, but which instruments do you take on the road?

I mostly play a guitar, and feature a mandolin and a fiddle during the show. I used to take a banjo and a bouzouki. Most gigs these days I’m playing solo or duo with my partner Jan [Fabricius] who sings. I have a couple of Martin 00-18’s. I have a 1937 that I use whenever possible, and then I have a new one, which is actually a Tim O’Brien model. I can take that one out of the country without anyone taking it away from me.

What kind of mandolin and fiddle do you have?

I have a Nugget Mandolin made by a guy from Michigan, Michael Kemnitzer—his nickname is Nugget. They always sound good. He’s quite well known in that world. I met him through a bluegrass songwriter friend. It’s funny how things happen with friends you meet. J.D. Hutchinson wrote songs that Hot Rize recorded. Since I was moving out to Colorado, he said I needed to talk with Michael about his Nugget mandolins. It turns out that J.D. is the one who told Nugget that he should make mandolins. He was a glass blower who made a banjo. J.D. said you could make mandolins—and you should. (Laughs) And now he makes these amazing mandolins. And I have a 1922 Carlo Micelli factory fiddle from Germany—made with a fake Italian name. (Laughs)

Photo credit Scott Simontacchi

What are your Top 5 favorite albums of all time?

Smash Hits – Roger Miller, on Dot Records.

Rubber Soul (1965 ) – The Beatles

Sweet Baby James (1970) – James Taylor

Strictly Instrumental (1967) – Flatt & Scruggs with Doc Watson , that was a big one.

Doc Watson on Stage (1971) – Doc Watson featuring Merle Watson

Help! (1965) – The Beatles. I remember the summer when it came out [August 6, 1965].

Tell us a “pinch me” moment when you thought “Wow, this is really happening to me!”

Just this last Thursday on the IBMA stage, at the rehearsal the night before, when Hazel Dickens and Alice Gerard got inducted into the Bluegrass Hall of Fame at the IBMA. I’ve been fans of theirs for a long time, and recorded some Hazel songs and some songs Alice sang. They asked me to participate in their performance. I got to sing. When I was rehearsing, I thought—man, this is so cool—I get to do this. And it’s sort of logical. It’s like sitting in with Doc Watson—at a jam at the end of a festival. There was one time when I got invited to play pretty much the whole set with him at RockyGrass Festival. It was like, wow! I always wanted to play like him and with him—and here I am doing it—and nothing really went wrong. (Laughs) It’s like you’re holding your breath thinking—this is happening to me?

Tim O’Brien photographed at Hardly Strictly Bluegrass in San Francisco, CA October 7, 2017©Jay Blakesberg

I’m sure there are other moments.

I was playing with Mark Knopfler—I was subbing for my friend whose wife had their first child and he was sitting out the tour in the U.S. for five weeks. One of the last gigs was in New York—at Reverend Ike’s church in Harlem. It’s a big theater. There I was playing in Manhattan for a sold out crowd. When I was warming up, I thought—this is really, really cool. Here I am in Mark Knopfler’s band—playing clawhammer banjo. I never thought I’d be here. It was cool to look out there, and it’s also weird because that’s what you’ve wanted to do. Then you do it, and think—it worked. I did it. (Laughs) And maybe I’ll never do it again, and I can accept that too.

Do you remember the first time you heard yourself on the radio?

When Hot Rize’s first record came out, I was on my way to a gig with another guy—not a Hot Rize gig. That record was on the radio, and I think it was my song. It was a pretty wonderful. Even more satisfying was hearing someone else sing my song. When Kathy Mattea did it, or when other people do it. After the Awards show this past Thursday—we went up to Frank Sullivan’s band’s suite for drinks and pizza. When we got off the elevator, there was a jam session in the hallway, and they were singing my song. I turned around and waved at them. I didn’t want to walk over and ruin it. But I thought—wow, this is awesome. People say they sing my songs all the time, but I rarely hear it. Here I was—hearing my song in the hallway. I surprised them, and they didn’t stop—so that was good.

Best advice someone has given you?

I really like that John Hartford advice: don’t get famous doing something you don’t like doing. There is an intersection between what you like to do and what people like to hear—and that’s your lifeline as an artist. If you can find that intersection, and once you grab them, sometimes you can take people to other places you’d like to go with your art. It is about following your heart. Joseph Campbell’s “follow your bliss” dovetails with that Hartford advice.

Photo credit Marty Fitzpatrick

How did you figure out where music fit into your life?

I was lucky early on to find something that really satisfied me—and that’s playing the guitar, playing music, singing, and putting that all together. I’m really lucky that I was able to do that. My parents weren’t encouraging me to do that for my living. They hoped that I would try it. The truth is—that’s what I needed to do. I’m glad that I followed it. I didn’t really know what else to do. (Laughs) Some people didn’t make the right choice because they never got in touch with that thing that drives them—or haven’t yet. I suppose it’s just not available to everybody. I tend to think it’s mostly because we haven’t investigated it enough.

Did someone help you?

Pete Wernick got me to be in Hot Rize because they wanted a good singer. And I’d never been the singer in a band. I’d been in bands, but maybe sang one song or sang harmony. That’s a powerful thing, if you can make that work—to write a song and sing it. Music on its own is a healing thing, and a great unifier. The spoken word is also. But when you combine the two—it’s a powerful cocktail. You can use it as a weapon or use it as a healing device. It becomes a responsibility—to do the right thing with it.

Best advice you’d like to give upcoming musicians.

When I started producing records, I was just trying to help people get the job done. Later on, when people asked me about producing I asked myself—I wonder what their goal is? Sometimes you can hear it right away. I think it’s important to ask yourself—what you can do with the music, and what you think is the best thing to do with it—and find that intersection. I am no better than anyone else. I screw up. But there’s a certain moral stance that helps you go on with the drudgery of the music business. If you have meaning yourself, within the music, then you can withstand the flames and arrows of the critics and fans—and you can steer around the pointless stuff. The creature comforts are nice, but you don’t want them to get in the way of the music or the substance abuse. Early on, I wasn’t that great at sports. I was shy. But with music I could be in society. I could do something. I could put my best foot forward. And I’m still trying to do that—that’s all.

What’s next?

Hot Rize tried to break up, but we were unsuccessful. (Laughs)

Isn’t that the year IBMA gave Hot Rize the first Entertainer of the Year Award?

Yes, that’s right. This coming year will be 40 years we’ve been together—or playing shows together. We’re going to regroup and concentrate a little more on Hot Rize next year. Everybody’s got their own thing that they do, but we’re going to try to honor it with reunion concerts in January, and do some video and audio recording—then a fall tour. These days you have to give a one-two-three punch.

Where can your new fans stay updated?

TimOBrien.net

comment closed