VIDEO FEATURE & WEB-EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW

Musician: BILL REICHENBACH

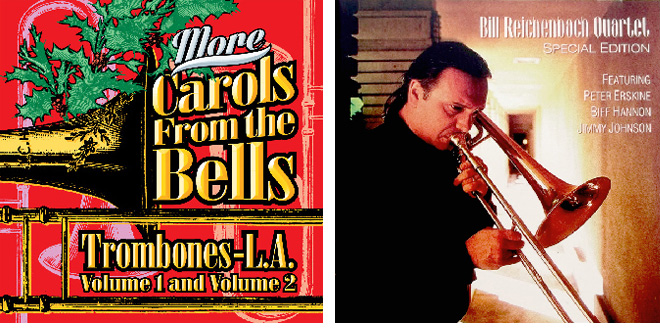

Music Video: “Carols From the Bells”

Musicians: Trombones-L.A.

Non-profit Benefit: Hearts of Music Fund

“My idea,” says Bill Reichenbach, “was to create this non-profit fund called the Hearts of Music Fund—for musicians who don’t have insurance. Back then, there were a lot of musicians who didn’t have insurance. And sadly there’s a good possibility starting next year, there will be a lot of musicians who won’t have insurance again.”

Reichenbach is a master of brass instruments. Critics have said that he “has surpassed all the expectations for the bass trombone and redefined new ones.” He’s an incredibly talented jazz trombonist and well-respected composer best known as a session musician for television, films, cartoons, and commercials. You can hear his tenor trombone on Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” and his bass trombone on numerous Hollywood films, commercials and albums—including a solo with Buddy Rich on “Wave.”

In 1981, he recorded a solo album, Special Edition, as the Bill Reichenbach Quartet featuring some of the most talented and respected musicians—Peter Erskine on drums, Biff Hannon on piano, and Jimmy Johnson on bass. The album reached number 10 on the national jazz radio play lists.

William Frank “Bill” Reichenbach Jr. started his jazz career while still in high school in Takoma Park, Maryland—just outside Washington, D.C. As one of the most sought-after studio musicians, he sometimes still ventures out of the commercial music world to play jazz. It’s in the blood that runs through him. His father, also named Bill Reichenbach, was Charlie Byrd’s regular drummer from 1962-73. The younger Reichenbach sat in with his father’s group at the famous Georgetown club “Blues Alley” where he played with jazz luminaries like Zoot Sims, Al Cohn, Clark Terry, Urbie Green, Milt Jackson and others. While studying at Eastman School of Music in Rochester, NY, with Emory Remington, one of the most well-known and influential trombone educators in history, Reichenbach continued to dig deeper into the jazz world. He was the featured jazz trombonist with the Eastman Jazz Ensemble when he started playing with Chuck Mangione.

After graduation, Reichenbach joined the Buddy Rich Band and was immediately featured because of his ability to play jazz on the bass trombone. In 1975, he moved to L.A. were he started playing the jazz tenor trombone chair on Toshiko Akiyoshi’s big band. At the same time, he was also the solo jazz trombone player on Don Menza’s big band. As a studio player, he has played on thousands of records and motion pictures, and countless TV shows and commercials.

After graduation, Reichenbach joined the Buddy Rich Band and was immediately featured because of his ability to play jazz on the bass trombone. In 1975, he moved to L.A. were he started playing the jazz tenor trombone chair on Toshiko Akiyoshi’s big band. At the same time, he was also the solo jazz trombone player on Don Menza’s big band. As a studio player, he has played on thousands of records and motion pictures, and countless TV shows and commercials.

The technically skilled Reichenbach has recorded with Quincy Jones, Barbra Streisand, Michael Jackson, Elton John, Toto, the Yellowjackets, Seawind, Frank Sinatra, Buddy Rich, Tony Bennett, David Foster, Aretha Franklin, Al Jarreau, Earth Wind & Fire, Dr. John, Ray Charles, Toshiko Akiyoshi, Don Menza, Tom Scott, and so many others.

As a writer and arranger, Reichenbach has worked on records for many well-known musicians including Michael Jackson, Quincy Jones, Aretha Franklin, Dr. John and Diana Ross. He has brought this history, knowledge and expertise to fresh, new arrangements of classic Christmas carols in an album released last month called More Christmas Carols From the Bells. Here, Reichenbach has gathered some of the most talented trombone session players in Hollywood to create an album that sets the tone for a festive, reverent and jazzy Holiday season.

We talked with Reichenbach about his creative process, how he approaches composing and arranging, and his idea of creating a non-profit fund to help Musicians in need. It is our hope that during this season of giving, the community of musicians and music lovers will help support his efforts.

BILL REICHENBACH Web-Exclusive Interview

with M Music & Musicians magazine publisher, Merlin David

How did the idea of interpreting/arranging Holiday carols?

Through some Trombone events, I met someone and we became friends. One year, maybe 1998, he said, “How would you like it if we came to your house and played Christmas carols for you.” As it turned out, he could only get a couple of guys to come over with him, and they had arrangements for four players, so I had to play anyway. (Laughs) We had invited a few neighbors, so there were 16 people—friends of ours, and we had some food. The people were so taken by the music. And it was music that he just had—that somebody had brought with them. The next year, I invited more friends. But I still hadn’t gotten the idea of writing/arranging Christmas carols. But this time we had about 16 trombone players in the back patio of our home—which had been renovated after the big 1994 Northridge earthquake. There were 50 people milling about in an area near my office. Everyone was jammed in one small place, and we played. And it was another smash hit.

How did it evolve from those first few years?

I immediately started thinking about the next year. I thought, ‘I can write some stuff.’ So I wrote 15 simple arrangements of Christmas carols—the first ones that come to mind. We had about 25 players that time, and then maybe 30 players. Then it started to grow—and we moved it to our front yard—because we just had our front courtyard completed.

How did you get the idea to create a Music Fund?

Around that same time, my wife Fran, our daughter Anah and I had taken some Landmark courses (you know, they are like the outgrowth of EST—only just a little easier on your body. (Laughs) The third course had this idea about leadership and organizing, and everyone had to come up with a project. My idea was to create this non-profit fund called the Hearts of Music Fund—for musicians who don’t have insurance. Back then, there were a lot of musicians who didn’t have insurance. And sadly there’s a good possibility starting next year, there will be a lot of musicians who won’t have insurance again. It’s scary. Then a friend of mine said “I go to this church where they have a long history of inviting trombone players. We could probably do a concert, play the Christmas carols, and take up an offering—and make some money for this Fund.” I immediately started writing more arrangements so that I’d have a whole concert worth of music. And this year will be the 12th concert at the Emmanuel Lutheran Church in North Hollywood.

How many arrangements do you have?

I think I’ve got about 40 arrangements, and they’re getting harder. The first ones I wrote were almost like you’d find them in a church hymnal. And maybe they’d have a little intro. Then I started getting into the idea of some of these other standard songs that are jazzy. And those I’d have to write full arrangements. And on this new project we have “O Holy Night” which evaded me for a long time until I figured out how to treat it. It’s sort of rhythmic, with drums and bass. And that gave me inspiration to try to write more creative longer arrangements that stand alone.

So you’re not just making the arrangements harder just to stump the incredibly talented 35 or so trombone players on stage?

Well, I’m not deliberately trying to stump the players. (Laughs)

Is there one carol that has always inspired you?

Ever since I was in second grade at JNA School in Takoma Park, Maryland, we had this great choir director, Mrs. Quade, and I learned so much music from her when I was in elementary school that I didn’t even realize until I got into college. She had a really good choir, and a pretty good big choir, and she also had a choir of first and second graders. When they did Christmas songs, it was good. And the first thing I ever performed as a musician was playing the drums for “The Little Drummer Boy.” I was in second grade—with that group. And there are pictures of it somewhere that my uncle took. My brother Kurt probably knows where they are. (Laughs) As I think about it, “Oh Come All Ye Faithful” was one of those traditional Christmas carols that still resonates with me the most.

Are there Holiday movies that continue to inspire you?

Oh yeah, there are a couple of them. There are various Christmas carol movies, and I’m not sure which one I like the best. But there’s also The Bishop’s Wife. I love that piece of music so much that I took it off the movie. And there are some newer ones like A Christmas Story—and I remember that one when it was new. And then, of course, It’s a Wonderful Life has always been so inspiring. Jimmy Stewart is so fantastic in that movie, and the story is so great. As a liberal, I see that movie, and it’s talking my language. (Laughs) And unfortunately the theme of the movie still resonates, and I think we’re going to have a big taste of that eventually if things go the way they look like they’re going to go.

You also did the music for some Christmas movies?

I played on a couple of Christmas movies—Scrooged, National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation, and about 1,000 movies.

Tell us how the new 2016 album More Carols From the Bells differs from the 2007 Carols From the Bells—or is it simply an extension of it?

You can think of it as an extension because basically I ran out of the first album. So I was going to have to get another pressing of that album, but I still wanted to record all the new arrangements I’ve done since that first album. Most of them are a little more involved. As it turned out, for purely financial reasons trying to be efficient with the money, we were able to make it a two-volume set. So it contains the first 25 tunes we recorded, and then these 15 new arrangements. So there are 40 tunes in this new two-volume set. Yeah, there’s a lot of stuff. By this time, when I’m starting to think about writing Christmas carol charts, I’m looking deeply into what I want to do—maybe “The Nutcracker Suite” or something. (Laughs)

The trombone community is a unique group of musicians.

Well, the trombone world is kind of a collegial group. We joke about it sometimes—we couldn’t imagine a choir of accordions. (Laughs) Although, when I was growing up, every time they did one of those New Year’s Day parades from Philadelphia, there was a band called the Mummers, and they dressed up in full Native American regalia, with the big hats and the feathers, and they marched down the street—all 150 of them. And the instrumentation of the band was saxophones, glockenspiels, accordions and banjos. (Laughs) They always played “The World is Waiting for the Sunrise.” That was their tune. And honestly, I’d never heard a sound like that before—or since. And I’ve mentioned it to a few people, and every once in a while someone will go, ‘Oh yeah, I remember that!” (Laughs)

Tell us how you got all these wonderful trombone players to be involved in this worthy cause?

Tell us how you got all these wonderful trombone players to be involved in this worthy cause?

When I went to college [Eastman School of Music in Rochester, NY]—that was my first exposure to a trombone Choir. And my teacher, Emory Remington, was like the godfather of symphony orchestra trombone players in America—or the world—for a quite a while. When I got into school in the late 60s, he had students in so many of the major symphony orchestras in the world—they went on to become the big teachers of the next generation. He had been in Eastman since the 20s. When I got there in the 60s, he had already been there for 45 years. So he was this legend. He taught a lot of students—he kept busy. He had about 28-30 students every year. He taught full time, five days a week, and maybe even a couple of lessons on Saturday—because that’s just want he wanted to do. So every Monday at 10 o’clock, we had trombone choir. There’d be 30 or so of us, and we’d start off with Bach chorales—which are very similar to the Christmas carols. And we would play through this. We used to joke that the tempo of the majority of what we played in that group was similar to his heartbeat (laughs)—because he was like 70 something, and for us in college, he was this old guy, and he would sing with us while we played. But we really got into that thing of what a trombone choir really sounded like. So when I came out here to California, every once in a while we tried to do something. And there are a couple of different groups here in Southern California. Like this Saturday, I’m going to be the grand marshal for Anaheim Trombone Day. I’m not conducting any of my own music. But there’s a group down there called Bones West, and it was started by an older student of my teacher from Eastman and a guy named George Roberts, who was a great studio bass trombone player out here in LA. Their whole musical direction is a little different. There might be 100 trombone players down there playing, including little kids. I rehearsed with them a couple of weeks ago and the median age of the group at that point was probably five years older than me—a lot of white hair. (Laughs) Fran and Anah are going to go down there with me and sell these new fundraiser CDs. They’ll have a big poster promoting it for us. So that will be kinda neat because it’s a big outdoor thing for the city of Anaheim, and there’ll be a lot of people there. We are just trying to create awareness.

How is Hearts of Music Fund helping musicians?

We raise money, and we never really have a ton of money, but we’ve had $10K or $12K in the bank at any given time—over the majority of the time. Basically, it’s an informal thing—from word of mouth. We hear about somebody going through financial problems—based on health-related issues. Either they were waiting to have some kind of surgery, and couldn’t afford it, or in one case we heard of a woman whose husband just died, and she was in that strange place between figuring out what little bit his estate was going to be able to do for her—and we paid her mortgage payment for one month and kept her in her house. I ran into a jazz tenor player this morning at the Union when I was running to a meeting. I didn’t even recognize him, and he came up to me and hugged me. As I was walking away, I heard him talking to someone behind me and he said, “That guy—that guy helped me out.” We gave him enough money to have some kind of minor surgery when he didn’t have any insurance. It’s a very informal thing. Now we have five people on the board—four musicians and Fran. It just makes it easier for her to be on the board because she ends up doing a lot of the business—the legal side of things.

How do you work with the Union?

Right now, there are two of us on the board at the Union, so we’re like a backstop. The union has a couple of emergency funds that they can give out—smaller amounts because they are limited by the union. And then if somebody is in dire need, the secretary in that particular office of the union taps us on the shoulder and asks us if there’s anything we can do to help. For the last about eight months, we’ve been down financially because we went through a little thing with our 501(c)(3) which is so complicated that a normal human can’t do it—unless you’re an attorney. It turns out they didn’t like the way we were dotting the i’s. So they let us lapse, and getting it fixed cost us a few thousand dollars out of the fund’s money to get it legal again. So, basically we’ve been waiting for this period of Christmastime to kind of throw more money into the bank so we can go back online and see if we can do anything for anybody. We are definitely looking for funds, and hope this new CD will raise awareness—and money. People can go to the HeartsofMusicFund.org, and there are pictures of some of the concerts, and people can contribute. There’s a PayPal button.

What is your vision for this Fund? And how can the music community rally around it to make it bigger?

I’m not thinking giant money. But if we were able to keep $25K or $30K at all times, we would be in a good position—and we wouldn’t have to say ‘No’ to anybody. We’re not going to be able to put anybody through major surgery, but what we usually try to do is to help somebody with a grand or two to fill that gap. Because we can keep it informal within the board and talk things out and examine the need, it makes it an easy situation for musicians who are reaching out. Obviously, there are limits to how far we can go with it, but that’s how much money we have. So if we had more money, we’d be less limited in our ability to help.

Tell us about some of the amazing musicians on this new CD—like working with the incomparable Peter Erskine.

Peter and I have been great friends ever since the early 80s. I actually met Peter when I worked on my first jazz album, Quartet. We recorded it in 1981 and released it in 1984. It was with Jimmy Johnson, the bass player, and Biff Hannon who is a piano player I went to school with. I believe I met Peter through Biff. He was instantaneously one of the greatest drummers I’d ever played with—and I’d already played with Buddy Rich and Steve Gadd. And we became friends, and he was connected with Jaco (Pastorius) through Weather Report. So I ended up doing Jaco’s Word of Mouth band. We did recordings here in LA, and then we went to Japan for a tour. And they did a recording of one of the concerts over there. Jaco was an unusual guy to work with. That’s a long story—you and I can talk about that just on our own. (Laughs)

Tell us about your work with Michael Jackson.

There was one time when I was actually in the limo with Michael. I got hired to write a string arrangement for a tune called “Muscles” that he wrote for Diana Ross. Jerry Hey would normally have been the guy to write it because he did all of Michael’s arrangements. But Jerry was in Europe or something, and he gave Michael my name—which was very unusual for Jerry to do. (Laughs) This was before Michael had the place in Neverland. He had a big mansion off Ventura Blvd. I went there and got to the gate of the property, and the guy there says, “Let me call.” And it turns out Michael is having dinner with Yul Brynner. So the guy says, “Well, you can wait here at the gate.” (Laughs) Now this was for a string session that’s supposed to happen later that evening—and I hadn’t heard the chart yet. I’m supposed to write the arrangement, and I’m waiting for Michael and Yul to finish dinner. Finally, after about 40 minutes, I’m looking at my watch and we’ve already gone past the time when the session’s supposed to start. The string players are already gathering in Hollywood, and there I am out there in the valley waiting for Michael in this old Rolls Royce that was not in prime condition. I’m sitting in the back seat and finally Michael gets in the car and he doesn’t notice me. And I said, “Hi Michael” and he almost jumped out of his skin because he didn’t know I was there. (Laughs)

Did you get to the studio?

Yes. So, we go down to the studio, and he gave me the track and I’ve got to sit there and scratch this arrangement out while string players were buzzing around me. And Michael is sort of sitting in the back in the dark, and you didn’t even know he was there. Getting him to participate in the session was a challenge—we had to pull him and say, “Come on, Michael.” (Laughs) I did everything he told me to do. Then later, they brought me back one more time because he had left this lick out. This was before digital so they couldn’t just grab something and add it. So we had another whole session of the same strings. Then I went out of town, and I heard they brought the string session in one more time. But Jerry was there this time—just to add a couple of more little things to it. (Laughs) So that was three different string sessions—for one arrangement of a tune that I don’t think did much. But that’s the record business sometimes.

Who influenced you to pick up the instruments you now play, and how old were you?

I started out playing drums—that’s what everybody at my house did. [Bill Jr. is the son of legendary jazz drummer Bill Reichenbach Sr.] Then around the time I was 10 years old I started hearing Dixieland music, and it appealed to me. So for my 11th birthday, my father said, “I’ll buy you a camera or a trombone.” And I said, “Oh, I want the trombone for sure.” And in a couple of years, I was playing in this band in downtown Washington DC called the Metropolitan Police Boys Band—a concert band led by my first trombone teacher’s father. It started out as something sponsored by the police department for underprivileged kids, but it turned out to be a lot of middle class kids—the ones that already had enough money to have private lessons. (Laughs) So we would all drive in from the suburbs and we would rehearse Marine Band music. I was the worst trombone player out of 13—when I was playing with that band. (Laughs) But I was sitting in the midst of all these players who were so much better than me. It was amazing. There were young trumpet players and I had never played with anyone like that before. And there were some pretty good trombone players. They also had a band room filled with all of these instruments—old beat-up, crappy, dirty brass instruments, and you could borrow them. I borrowed a baritone sax, baritone horn, small tuba. I would take them home and clean them up and take them down to the basement and play on them until I could make some sense out of it. And that was the beginning of playing other instruments—and it was so worthwhile. Now, I play tuba on The Simpsons, American Dad!, Family Guy—and sometimes even on records. I played jazz tuba on one of Wayne Bergeron’s albums. So that’s been kind of a kick for me. I like playing tuba—it’s kinda fun. And it’s been good for my job.

Do you write on keyboards?

Yes. I have computer programs, and a keyboard that’s connected to it. I use a Finale program which is for copying music, but you can compose in it. It’s not exactly the best sequencing program. It’s not like Digital Performer or Pro Tools, but when you’re finished—you can make parts that people can play from. You can actually create scores in that—and play it using a sample library. I’ve written a couple of full wind ensemble pieces—classical style pieces—and some orchestral music with the string samples. It’s fun to do it, and you can sit there and be obsessive and nobody’s going to bother you. (Laughs)

Tell us about the other instruments you play.

Well, the brass instruments are all kind of related. There’s valve trombone. And contrabass trombone—which is bigger than the bass trombone and I play that a lot on some of these big, loud, action movies—lot of writing for contrabass trombone now. The euphonium, which is like a small tuba, and the bass trumpet—which is like a valve trombone except it looks like a big trumpet—and it’s really a better instrument. So my choice when I go out to play jazz, which is unfortunately not that often anymore, is to take the bass trumpet, and the bass trombone. Because the bass trumpet plays in the same range as the tenor trombone, but it’s a little different style. I can think differently when I’m playing valves.

What composing/arranging tip would you like to offer musicians who look up to you?

It’s like the story of how do you make a sculpture. You start with a big rock and take away all the stuff that doesn’t look like the guy you want it to look like. Especially with all the electronic equipment we have now, writing is a good place where you can sit down and work through your arrangement and make it flow. And you can hear it. But after you’ve done that, you need to go out and have it played by real musicians. You won’t believe how much better it sounds played by real musicians. All of a sudden, there’s life to it. When I was in School at Eastman studying arranging and composition, we were doing it the traditional way because none of this other stuff existed. There were no sequencers—there were no computers. So when you had to write an arrangement, you might have to write it overnight, copy it and bring it in—and then you got to hear it, which is a little bit like the music business. That’s what a lot of people got trained on, and if you made a mistake, you’d have to erase it or cross it off and rewrite it. (Laughs) I remember one of the first charts I wrote for big band was “Watermelon Man”—and it was awful. (Laughs) I didn’t understand anything about writing for saxophones. I transposed it correctly, but I didn’t know how to make the section sound balanced between altos, tenors and baritones. When I got to Eastman and studied arranging, this great teacher said, “Well, there’s a trick for that.” He said, “Write the parts transposed on the score and then look at them. And if they’re all kind of sitting around the same place on the score—they’re going to balance.” It’s as easy as that. (Laughs) But I didn’t know that back then—in high school!

Who inspired you to write music?

My father dabbled in writing arrangements. I never saw him do it, but there was evidence of it. He had piles of manuscript paper around the house—things that were handwritten by him in the early 50s and middle 40s. I don’t know what any of them sounded like. We never played any of it, or heard any of it. But I was interested, and I started listening to old 1920s records of Duke Ellington’s band, where they had tuba and banjo—I think it was called the Jungle Band. And I was so fascinated with that sound. When we ended up doing a show called Frank’s Place for a couple of years out here, and I was writing music for it, I was able to use that sound a few times. I was able to steal that sound from Duke Ellington—the old pre-big band African sounding music. So the whole idea of trying to make instrumental colors work was always interesting to me. In high school, I did a lot of choral arranging because the only ensemble we had at Takoma Academy was the choir. Leland Tetz—he was the guy. When you had an ensemble that he put together, it sounded good. And the band sucked. (Laughs) So I was more likely to write arrangements for the choir to try my hand at composing. We would have a “Week of Prayer” every once in a while and one year they let me put a small choral group together to be like the choir. So I wrote a couple of little connective bits like we’d use in a church service—just little things. It was my first try at composing. And it was such a wild feeling—and that just stuck with me. So by the time I got to college I was caught between—do I want to be a composer or do I want to be a player. And I went through that for a long time during college. It finally came down to the fact that I’m a little bit more social, and being a composer, at least the way I would do it—you are by yourself. And I liked being around players. So this way, I’m doing arrangements on my own and I get into the mood of writing until I’m done with it but I don’t have to survive on it—which is the best way for me.

Where were you when you first heard a song you recorded being played on the radio?

When I was at Eastman, I played with Chuck Mangione—on the 1970 Friends & Love album. He did a bunch of albums during that time, and I played on all those albums that became radio hits—especially in the upper New York state area. I’d be in clubs, and I’d hear some of those songs on the radio. And it was like, “Ooh, wow!” It was quite an experience. Then I got out here [California] and I started doing a lot of records with Jerry Hey and that horn section, and we started doing all those Quincy Jones and David Foster albums. I’d hear something on the radio, and sometimes I’d forget that I played on it. (Laughs) I didn’t realize it but it’s fun to look back at songs I played on. Now, somebody’s made a Spotify list called Jerry Hey Bonanza, and it’s got maybe 500 tunes on it—and I played on most of them. And that’s just the ones that stick out. There’s probably another thousand that are forgettable. (Laughs)

Tell us about a musical hero you played with.

I would have to say the first Chuck Mangione concert with the orchestra. He had Steve Gadd playing [drums], and Tony Levin [bass], and Al Porchino played lead trumpet, and Lew Soloff [Blood, Sweat & Tears] on trumpet, and all of those guys. Now that was new music at the time. And then going on Buddy Rich’s band was very exciting. And in my late career here now, next week we’re going to start doing the eighth Star Wars movie with John Williams. And I’ll have to say that being in the room with him, and to play his music—with him—is a gift. He is so together, and so professional—he brings the best out of everybody in the room. He’s so gentle with everyone. It’s just an outrageous experience—and I’m so lucky to be there.

What instrument/equipment can you not live without—that helps you write, record or perform?

The trombones that I play are handmade by Gary Greenhoe. He was another trombone player from Eastman, a couple of years older than me, but he came back for one year while I was there. So we have that connection. He was always into this mechanical stuff, in addition to being a great trombone player. He invented a new version of the rotary valve that we use on these horns—like bass trombones. Then he went from that to building modified horns. He’d take existing horns and he’d modify it with a few of his parts. Then he started making his own whole horns. I was very lucky to kinda be working with him on that stuff—to get what we thought was a great trombone built. So I have three of his horns. I’ll never need to buy another bass trombone. They are fantastic. I believe now he’s sold the license to build his horns, his plans and some of his tooling to a company in Chicago called Schilke. I think they’re going to be building his trombones. I trust they will adhere to his standards. They’ve been making great trumpets for years.

Bill Reichenbach with JJ Abrams

Top 5 Musicians or Composers who inspired you to become a musician?

Duke Ellington, Thad Jones, Ralph Vaughan Williams, John Williams, and J. S. Bach—really!

What are your Top 5 favorite albums of all time—that still inspire you when you hear them?

My Fair Lady (1956) – Shelly Manne & His Friends

Giant Steps (1960) – John Coltrane

’63: The Concert Jazz Band (1963) – Gerry Mulligan

Mass in G Minor – Ralph Vaughan Williams (Roger Wagner Recording)

Bill Evans Trio with Symphony Orchestra (1965) – Bill Evans

What are the Top 5 favorite albums you’ve played on—that you continue to be proud being a part of that project?

High Crime (1984) – Al Jarreau

Road Time (1976) – Toshiko Akiyoshi-Lew Tabackin Big Band

Word of Mouth (1981) – Jaco Pastorius

Loopified (2014) – Dirty Loops

John Williams Plays Steve Spielberg’s Favorites (2017) – John Williams (not yet released)

Bill Reichenbach with Carole King

Best advice someone has given you.

Try not to sweat the small stuff.

Best advice you’d like to give.

To a musician—try to become a part of whatever music you’re playing.

Which PRO are you with?

I belong to ASCAP. It’s always nice to find that something you did, maybe years ago, still has some value.

What’s next for Hearts of Music Fund?

This is our big fundraising season, so we’re just trying our best to put some money in the bank. We’ll sell CDs and take up an offering at the concert—we’ll make a few thousand dollars there, and we’ll keep selling the CDs. And it’s also available on CDBaby. We’ll just have to see how it goes. We’re getting a little bit more public this time. I’m going to have a telephone interview this week with a guy from England who has a jazz radio show. He must be looking at Facebook because when we announced this new Christmas album would be available, within an hour, we had a request from him saying, “I want to interview you for our show.” And people can always go to HeartsofMusicFund.org—and donate there.

Note:

We here, at Mmusicmag.com, will continue throughout 2017 to interview other musicians who are involved with Hearts of Music Fund.

To help this weekend:

Trombones-L.A. conducted by Bill Reichenbach has a Fundraising Concert

Sunday, December 18, 2016—Admission is Free

Emmanuel Lutheran Church

6020 Radford Avenue (at the corner of Radford & Oxnard—2 blocks east of Laurel Canyon)

North Hollywood, CA 91606

For more information on Hearts of Music Fund and to stay updated:

HeartsofMusicFund.org

BillReichenbach.com

comment closed