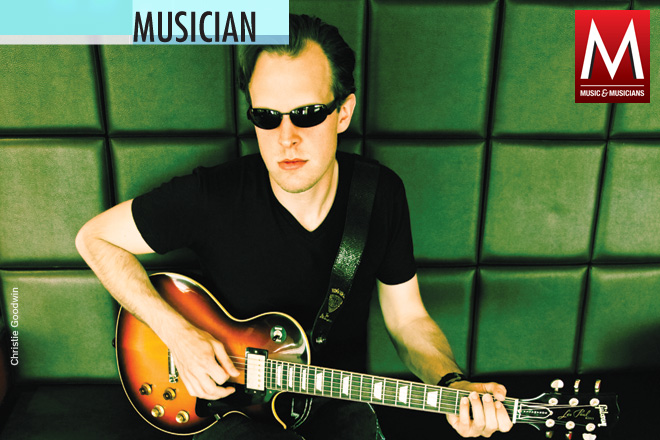

JOE BONAMASSA

Goodbye to the rib joints, hello to blues-rock guitar hero status

By Russell Hall

“People told me I was destined to play rib joints and biker rallies all my life,” says Joe Bonamassa, reflecting on his early years as a struggling blues-rock guitarist. “But I knew there had to be a better way.” But more than a decade and a half into his career, today Bonamassa has arrived at the pinnacle of the blues-rock world—and he’s done it without the help of a record label. “People think my manager and I sat down and hatched a master plan,” says Bonamassa, who has spent most of his career releasing albums through J&R Adventures, the label he started with manager Roy Weisman. “But it was really just a case of necessity being the mother of invention. We didn’t have a label that believed in us musically, so we decided to own and control everything ourselves. That way, if we failed, we did it on our terms.”

Record labels might not have believed in Bonamassa, but his guitar-slinging forbears certainly did. Befriended by blues legend B.B. King when he was just 10, Bonamassa went on tour as a pre-teen with the likes of King, Buddy Guy, Robert Cray and John Lee Hooker. A friendship with the late Danny Gatton helped to expand his musical horizons, and at age 14 he co-founded the band Bloodline with sons of Miles Davis, Robby Krieger and the Allman Brothers Band’s Berry Oakley. Bloodline recorded a self-titled album for Capitol Records in 1995 before breaking up, but now Bonamassa has a new supergroup alongside first- and second-generation rock royalty: Black Country Communion, which features Bonamassa, Glenn Hughes, Jason Bonham and Derek Sherinian.

His new solo effort, Dust Bowl, finds Bonamassa mixing incendiary originals with gritty covers like John Hiatt’s “Tennessee Plates” and Free’s “Heartbreaker.” The acclaimed six-stringer also recently wrapped up work on the second Black Country Communion album, set to be released in June and followed by a tour early next year. Bonamassa spoke with us about his guitar roots, his aversion to demos and the advice he received from the King of the Blues.

What was your goal for this album?

To find new ways of doing things. We’re all the sum of our history. After a while, we start to create certain patterns in what we do. I wanted to break some of that repetition. If you keep to the same format, the vibe stays the same, even though the music might change. If you want to grow, you have to break down walls and find ways to work that are different from the past.

How did you do that?

I grew up listening to classical music, to players whose performance level was very high. The desire to play at that level was instilled in me. The question then becomes, how do you achieve that—by constantly redoing something? Or do you achieve it by being so proficient that you’re able to pull off something great at any given moment? Classical musicians don’t make music the way rock artists do, where there’s lots of overdubbing. They’re so well rehearsed, their performance level is so high, they just go in and nail it—capturing a real performance. On this album I tried to strike a balance between those two ways of doing things.

Does that involve practice?

Absolutely. Practice is key. But a lot of the music I love—folk, blues, rock and pop—is wonderful when it’s rough and off-the-cuff. That’s one polarity, and that’s predominantly my type of music. But then there’s the other polarity that involves a higher level of performance. It’s not fair to say there’s no place in pop music for that type of excellence. Stevie Wonder’s vocals are a good example: He gets great performances in single takes. It all comes down to how listenable the music is. That’s what counts, first and foremost.

How did you learn to play?

I started playing piano when I was 5. When I got a guitar, I sat at the piano with the guitar in my lap and taught myself the notes using what I’d learned on piano. I took lessons from Wayne Wood—who was the guy in Austin—for a few months and learned some theory. But as far as learning songs, learning music, that came either from watching friends play or from picking out parts on albums.

What artists did you like then?

When I was really young, it was the Ventures. Then as I started to play in bands, I started listening to the Rolling Stones and the Yardbirds. This was 1966 and 1967. And then Hendrix came along. His lead playing was phenomenal, but that was just part of a larger picture. I remember reading articles where Hendrix would say, “Guitar players need to learn how to play rhythm guitar.” He was a big proponent of rhythm playing and composition. He exemplified what it meant to be a complete guitar player.

What’s your writing process like?

I’ve yet to find a standard way to write. I’ve learned it’s better to be open to different approaches. That doesn’t mean you don’t need to have your sound together and your playing together, and have pretty good clarity about what you want to do before you go into the studio. At least that gives you a strong, clear springboard from which to work. There have been instances in the studio where something has come to me out of nowhere, but that’s rare.

How do you relate to producers?

I’m becoming more open to getting feedback from other people. Even if you’re able to produce yourself well, it behooves you to get other opinions. No matter how good you are at orchestrating, arranging or seeing the big picture, it’s extremely difficult to have a 360-degree view. As I get older, I’m finding I get a bit exhausted trying to take that wide view. If I can get positive criticism in the studio, that’s great.

What’s your recording setup?

I use the Nuendo system, which is a digital platform. To me, the top end sounds more open and sweet using Nuendo than Pro Tools. That could change from year to year, as both systems come out with new and better versions. I do use analog gear to process things, and to mix through.

What are your thoughts on shredding?

I’m probably the wrong guy to ask—I’m sometimes hypocritical. I might do a show, shred a 15-minute solo, and then listen to the tape and think, “What am I doing? That was good for about two minutes!” That sort of playing is OK if it’s done within the context of a song, but I fell in love with the guitar because I heard Brian Jones play a cool fuzz-tone lick on “Satisfaction,” and because I heard Hendrix do the same thing on “May This Be Love.” What turned me on were things like Eric Clapton’s tone on [Cream’s] “Sleepy Time Time.” If I had been 10 years old during the ’80s instead of in the ’60s, I’m not sure I would ever have picked up an electric guitar.

How was it playing Hendrix’s Strat?

Halfway through the performance, I wanted to run out the back door of the venue with it! I definitely felt a certain vibe as I was playing it. Everything has its own frequency. I once read a story about a guitar player who didn’t like the sound of his instrument. Rather than changing pickups or configuration, he decided to just will it into sounding different as he practiced. And after months and months of playing, that guitar did in fact sound totally different. I believe that story. I think an artist leaves some of himself in what he’s touched—and there are a lot of Hendrix’s vibes in that guitar.

What’s next?

I’ve been working on an acoustic album, and have three songs cut so far. People have been asking me to do this for a long time. It’s pretty much just me playing the songs solo, live in the studio. I want to get it finished this year, though I’ve got to balance that with touring. I also have a bunch of new electric guitar–based songs that I want to record. I would also love to write music for an orchestra. That’s a direction I would like to go as an electric player.

When did you start playing?

I first held a guitar when I was 3 and started playing when I was 4. I was always picking it up. It never got old. I started playing classical guitar, but that involved too much discipline. The blues, on the other hand, is a blank canvas. There are no rules—you can interpret it any way you want. That really appealed to me, and it still does.

How did you learn?

I listened to albums and tried to emulate my heroes. My influences early on were Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, Rory Gallagher and Paul Kossoff of Free. It was great to stumble upon all those great British blues artists who had been influenced by American artists.

What did you admire about Kossoff?

He’s such an unsung hero. I recently watched a bunch of concert footage of him playing with Free just before their big hit, “All Right Now.” They never got the notice that Led Zeppelin got, but they were just as innovative.

Kossoff’s playing cuts like a knife through butter. You can feel his emotions in every note, whether it’s a hard note or a soft one. He’s a tactile player, and the tone he got with that beautiful ’59 Les Paul was just crushing. I actually got to play that guitar at a show in Newcastle last year. A friend of a friend owns it, and he let me borrow it. That was a thrill. I felt like I was channeling Kossoff.

How about Danny Gatton?

He turned my world from mono to stereo. He said, “You know, kid, you know something about the blues, but you don’t know anything about jazz and rockabilly.” He had this Virginia way of speaking. He got me listening to people like Howard Reed, Wes Montgomery, Charlie Christian, Jimmy Bryant, James Burton and Duane Eddy. That opened up my world.

Did B.B. King give you any advice?

Watch your money and keep your eye on the business side. It’s about music, but it’s also about business. When I walk onstage, I see that as a privilege. I don’t think about how much people paid for tickets—though I am sensitive to that—and I don’t pay attention to how much money I’m making on a given night. I play with the same intensity no matter what. But B.B. King sat me down and said, “Joe, you need to always reinvest back into what you do, back into your fan base. Fans can detect if you’re not doing that, if you’re not doing things to improve the show.” It’s no different from running a Walgreens or a Joe’s Pizza Shack.

How do you practice?

I try to practice things that are outside my normal sphere. I tend to pick up an acoustic guitar or a mandolin instead of just hammering something out with a Les Paul and a Marshall. I might practice prog rock. In live shows we sometimes do Yes’ “Heart of the Sunrise.” We used to do Genesis’ “Los Endos,” from their A Trick of the Tail album.

How do you construct solos?

They’re nearly always improvised, even in the studio. Solos are a reaction to what’s going on around me. The new album is more oriented toward melody and songwriting structure than the previous albums, and having that solid framework can help power a solo. I have great players, and I often react to what they’re doing. They take me to a good place.

Is rhythm guitar underappreciated?

Absolutely. Even someone like me, who often gets caught up in soloing, plays rhythm guitar 80 percent of the time. Even a guy who puts on a “guitar show” has to play rhythm, and has to be fluent in chords and voicings. Also, if you don’t learn how to back off your volume when someone else is soloing, that’s problematic. Rhythm playing is about learning how to blend with the band and be part of the ensemble.

Do you have a home studio?

No. I have GarageBand and the little built-in microphone that Apple provides. I hate making demos. I always feel I’d rather be making the real thing. The first thing you play—your first instincts—are the most inspired, and I’m always fearful of losing that. I make the world’s worst demos. They’re distorted, sloppy and usually played on the wrong guitar. Our demos aren’t elaborate.

Do you prefer digital recording?

I’ve used Pro Tools to do all but one album. The only album in analog was my first, with [producer] Tom Dowd. It all gets whacked down to “1s” and “0s” anyway. Maybe audiophiles can hear the difference on their $15,000 turntables, but that’s not who I’m making albums for. I’m making albums for people who put an iPod in their car or a CD in their player. I truly don’t hear the difference. Plus if you play a CD inside a Pontiac it sounds completely different from how it sounds in a BMW. At that point analog versus digital becomes a moot point.

Why do you usually play Gibsons?

It’s about how well those guitars channel what you hear in your head. There’s no better guitar than a Les Paul to achieve a warm and inviting tone. Even when I played a Strat, I always found myself trying to make it sound like a Gibson. I would roll off the treble so much and put so many boosts on it that in the end I would think, “Hell, I might as well just play the Les Paul.”

Does blues have a future?

I see kids in the audience who are 14 or 15, and even kids as young as 4 or 5. It used to be all old dudes, but now it’s guys and girls of all ages. The audience has become really varied, and we’ve done surprisingly well with women. Based on who I see at the shows, I’m not worried at all about the future of the blues.

comment closed