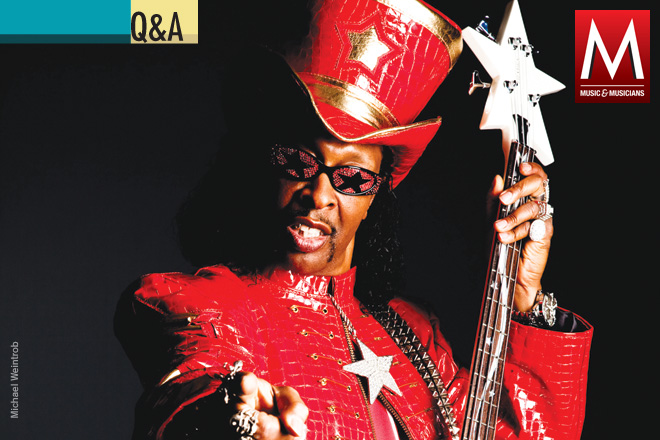

BOOTSY COLLINS

The funkiest bass player in the universe throws an all-star party

“I am the funk, I’m with the funk, the funk is within me,” declares legendary bass player Bootsy Collins—and you’d better believe it. Whether holding down the mighty grooves of James Brown’s early-1970s band the J.B.’s, slapping his way through extraterrestrial funk workouts with George Clinton’s Parliament-Funkadelic, charting solo hits such as “Bootzilla,” or collaborating with everyone from popsters Deee-Lite to bluegrass icon Del McCoury, the much-sampled Rock and Roll Hall of Famer has always given us earthlings the funk, the whole funk and nothing but the funk.

Collins continues to funkify the masses with his latest release, Tha Funk Capital of the World. With his trademark star-shaped space bass firmly in hand, the funkateer surrounds himself with a wide range of all-star talent, from Snoop Dogg and Samuel L. Jackson to the Rev. Al Sharpton and Béla Fleck. “I’m into changing things up,” explains Collins. “I wanted to add a little rap, a little rock and little gospel in with the funk—and come up with a thing where I can break into a whole new area.” He has also been recording with Sly Stone on what is slated to be the reclusive R&B master’s first new album since 1982. We spoke with Collins at his Bootzilla World Headquarters in Cincinnati about his music, his business and the cosmic importance of the one.

What’s behind the album title?

One night I looked up at the universe, saw the stars and thought, “I need a title for this record.” I woke up the next day with Tha Funk Capital of the World. As soon as I said it, I thought, “Wow, that’s it!” It has more than one meaning. I like that. You can marinate on it. I knew, first off, people would think I was talking about a certain city. So that was fine. Then it could be deeper than that. Wherever I’m at is where the funk is. But it also tells people that it’s wherever you’re at. What you bring to the table, that’s pretty much what it’s gonna be.

How did you work with your guests?

Each song dictated a different approach. For example, on “Freedumb,” I invited Dr. Cornel West in because I had this concept I wanted him to speak about. What I told him was, we all got these smartphones, but everybody’s still making dumb decisions. (laughs) He took that, and what you hear on the record is what he came up with. He didn’t write anything down. It came off the top of his head. It was fun and encouraging to watch that process, because that’s how we used to do it back in the day. Just off the top. Reverend Sharpton and Samuel L. were the same way on their songs. Didn’t write nothing down. I gave them a direction, and they took off.

Where does that “off-the-top” approach come from?

That idea is about dedication to music. It’s hard for younger people to be dedicated to music when they’ve got so many distractions. Twitter, Facebook, video games, all these different things. Back in the day, we would kill ourselves to rehearse. I don’t care what was going on, we had to rehearse. It takes that kind of dedication to lead with the music and to create the expression of what you’re feeling. You have to be focused like a boxer going off to training camp. No sex, no drugs—just total focus. It’s a hard thing to do, but that’s what made the great ones great. Michael Jordan, Jimi Hendrix, these cats were dedicated. They practiced and got great at their craft. It wasn’t about going out and saying, “Hey, everybody throw your hands up!” It’s like, “Throw my hands up? You haven’t done anything yet. Do something and I’ll throw my hands up.” We’re asking now for applause and credit before we even do anything. It’s a little backwards.

What did you learn from James Brown?

He taught me about the one. That first beat of the measure. When I got with him, I was playing a lot of notes. I had grown up playing guitar, and I was forced into playing bass because I wanted to play with my brother [Phelps “Catfish” Collins], who played guitar. But when I joined James’ band, I didn’t have all the natural attributes that bass players have. I was playing like a guitar player. But James disciplined me, settled me down. His whole thing was, “You can play that stuff, but make sure you give me the one.” The one was so important to him.

Did he give you extramusical advice?

He told me, “It’s 75 percent business, 25 percent music.” For me it was all about the music, so I didn’t know what he was talking about. But he let me hang around and see him take care of business, make those phone calls, go to the promoter’s office. All these different things didn’t make sense to me then. Later on, I got it. I thought, “That’s why he made that phone call,” or, “That’s why he cussed out so-and-so in front of me.” It all benefited me.

What’s up with Sly?

He’s doing a solo album with remakes as well as new songs. I played on “Hot Fun in the Summertime,” one of my all-time favorites. Sly was one of the main cats who opened the door for us freaky black entertainers. He and Jimi opened a whole new door that said, “Yeah, it’s cool to look and sound like this.”

How’s he doing?

Sly is going to be Sly. That’s the way he came up, and I think it would be hard for him to change. I understand. When you’re coming up and you’re dedicated to music like he was, and then you find out that the business has corrupted every part of the musical vision that you’ve intended, it affects you deeply. I know what I’m talking about, because I went through the same thing. I fell out the back door of it all and landed on my feet. Sly, he don’t want to deal with it. A lot of the ’60s and ’70s musicians are not here because they didn’t want to deal with it. They took themselves out of the picture. That business aspect of music is no joke. I got into this because I loved music, but the business aspect can ruin that for you.

How do you feel about sampling?

In a way, it’s been great. And in another, it hasn’t been so good—especially for black youth, because they are following more of the rap lifestyle than the musicianship. There isn’t enough balance there. The musician side needs to come up some. Hopefully I can help more people get involved in playing music on real instruments. I know that they’ve put down the Guitar Hero games because the violent killing games were earning more money. When it becomes about the paper gods so much that you’ve got to worship that lifestyle, then things are out of whack. You can’t be creative with the wrong priorities, but that’s what it has come to. We need to instill music values.

–Bill DeMain

comment closed