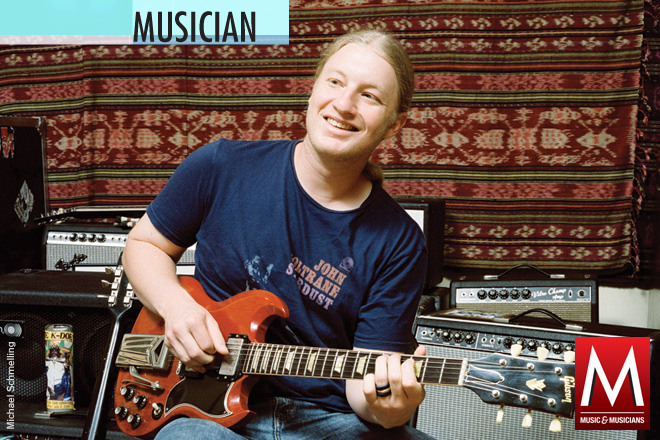

DEREK TRUCKS

He learned from the masters how to make his guitar sing

By Russell Hall

Derek Trucks was born to make music. The nephew of Allman Brothers Band drummer Butch Trucks, he was named after Eric Clapton’s early-1970s outfit Derek and the Dominos. So it was only natural when Trucks took up slide guitar at 9, formed the Derek Trucks Band at 14 and sat in with the likes of Bob Dylan, John Lee Hooker and Buddy Guy while still in his teens. “I have the sort of personality that allows me to sit and watch, and learn from observing,” he says. It seemed like fate when in 1999 he became a member of the Allman Brothers Band, and again eight years later when he backed Clapton on tour.

Along the way, Trucks forged a style that drew not only from blues and rock, but also from jazz and classical Indian music. “Any music that has a hard folk element, or any music that has roots in poverty and striving, has common themes in every part of the world,” explains the guitarist, now 31. “I definitely hear strong connections in Indian folk and classical music, and the blues.” Those influences are in full evidence on Roadsongs, the Derek Trucks Band’s recent live double album, recorded at Park West in Chicago. Roadsongs marks a summation of the group’s 16-year career as it begins an indefinite hiatus. “We felt it was a good time to try something different for a while,” he says. “You have to be fearless sometimes. If you feel it’s time for a change, you can’t be afraid to do that. But you also have to nurture a band in order to keep it together.”

Trucks has been anything but idle, however, as recent months have seen him working with jazz greats Herbie Hancock and Wayne Shorter. He and his wife, guitarist and singer Susan Tedeschi, are at work on a much-anticipated collaborative album scheduled for release next year. From his home in Jacksonville, Fla., Trucks spoke with us about his influences, his approach to the guitar and his key role in two renowned bands.

Why did you select Chicago to record Roadsongs?

One of those Chicago shows really stood out. Several of the guys told me if we ever do a live record, that show should get the first look. When we’re touring, everyone tends to be critical and wants to tweak things afterwards, so it was rare to hear the other side of that. One idea we considered was to pick the best version we could find of every tune—sifting through every performance—but we ended up finding out that the best versions were from that same show. Having a horn section there, which is something we only did in Chicago, played into the decision as well.

Who are your main influences?

Duane Allman’s slide was the first sound that really grabbed me, especially the intro to “Statesboro Blues.” Elmore James had a huge impact as well. They were my first influences, and they’re probably still the biggest. Then there are several jazz players, many of whom are horn players: Wayne Shorter, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, the obvious ones. Charlie Christian had an impact as well. Mahalia Jackson, Aretha Franklin, Otis Redding and Bobby Womack are some singers who’ve influenced my playing.

In what way?

Making the guitar sound like the human voice, making what you play lyrical and making everything count, in the sense of not wasting notes. When I hear Duane Allman play guitar, I also hear Otis Redding singing. They’re doing different things, but it still sounds like blood pouring from an open wound. When I first heard Aubrey Ghent, one of the great sacred steel players, it dawned on me that I could sing through the instrument, or do something similar to all the great singers I had been listening to. [Derek Trucks Band bass player] Todd Smallie and I went to Ali Akbar College of Music in San Rafael, Calif. Ali Akbar Khan makes all his students take vocal classes. He believes that when you’re playing, you should be “singing,” whether you’re actually singing or not. That concept is incredibly important. You can hear it in the playing of Duane Allman, Eric Clapton and Jimi Hendrix. Great players are able to tap into emotions that you can’t put into words. It gives their playing an extra dimension.

Does playing slide help?

It certainly gives you a more direct route. I often think back to some of the early Delta blues players. They would sing a line, and then the next time the line came around, they would play it on slide instead of singing it. They would use the slide to mimic the female voice.

Was joining the Allmans difficult when you were just 20?

In a band like the Allman Brothers, which is very improvisational, you have to be able to grab the bull by its horns. Especially when Dickey Betts was still in the band, figuring out how best to do that, while still deferring, was difficult. When it became just Jimmy Herring and me on guitars [following Betts’ departure in 2000], the situation went from Dickey completely running the ship to, “OK, we’ve got to figure this out.” That was probably the biggest challenge. But even with my own band, that took a while. I put a band together when I was 14, and when you have guys in the band who are 35, or pushing 40, it takes time to earn their respect. Only when that happens can you become an actual bandleader. You can’t jump into a situation like the Allman Brothers with both feet and do what you think you have to do. You have to feel your way through it.

Is it true you studied the original versions of their recordings?

Yes. I wanted to get it back to the roots of it all. The band had been through lots of changes. They had a great run in the ’90s, and the various incarnations—but my favorite was always the original band. When I joined, [bass player] Oteil Burbridge and I went back to what [original Allmans bass player] Berry [Oakley] and Duane were playing, and brought that back to the band, sometimes without the guys even realizing that the harmonies had changed. After a while, you could feel the guys instinctively sensing that things were veering back to heart of those songs.

How does it compare to your band?

It’s much more of a free-flowing leadership in the Allman Brothers. The Allman Brothers are also a historic institution. You’re not necessarily keeping one foot in the past, but you need to have reverence for what’s been done. In my own group, it’s more straightforward. There’s no template that tells you what you have to do—it’s easier to jump around. The roles are totally different.

What draws you to the Gibson SG?

A lot of it is about comfort. The SG was the first guitar I felt great about, and it’s become second nature to me. Most of the time, I don’t even think about the instrument. Once you get comfortable with a guitar, and you know where the sweet spots are, it almost disappears from your mind and becomes part of you. At that point you get the instrument out of the way and just go about the work of trying to find melodies and so forth.

Why don’t you use a pick?

I prefer that sound of flesh on the strings. I also feel that I’m better able to get across what I’m hearing in my head without a pick.

What did you learn from touring with Clapton?

Digging into his catalog—especially the Derek and the Dominos era—I came to love the way he would craft a song. He always seems to have a bit of firepower in his back pocket. He doesn’t show his hand every night. There’s a reserved aspect to his playing that I think a lot of younger musicians overlook. It’s the same thing that makes B.B. King so great. You sense there’s something in reserve. It’s like a baseball pitcher who has a 98-mile-per-hour fastball that he breaks out only when he needs it. Every once in a while they surprise you, and it’s that threat of more that makes their playing exciting.

comment closed