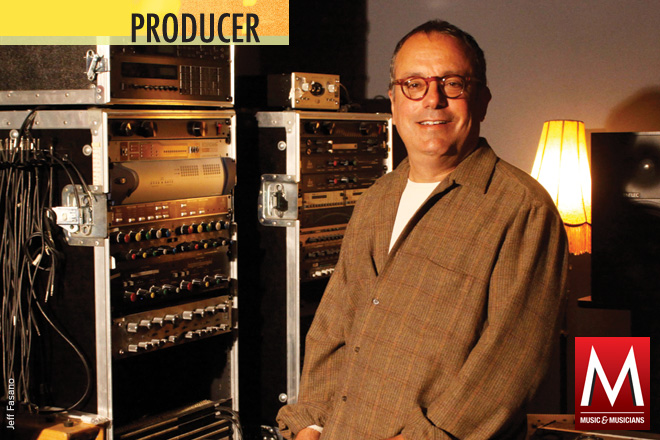

LARRY KLEIN

This innovative producer is more than just a ladies’ man

By Jeff Tamarkin

What do Joni Mitchell, Madeleine Peyroux, Julia Fordham, Melody Gardot, Shawn Colvin, Mary Black, Luciana Souza and Tracy Chapman have in common? Sure, they’re all highly acclaimed female singers. But they also have the distinction of having collaborated with producer Larry Klein. (Two have also been married to him—Mitchell from 1982 to 1994 and Souza since 2006.) Not surprisingly, then, Southern California native Klein has staked a claim as the go-to producer for strong, individualistic women with powerful voices.

But Klein can’t be pigeonholed quite so easily. He also co-produced Herbie Hancock’s 2007 Album of the Year Grammy winner, River: The Joni Letters, has produced other male artists such as Steely Dan’s Walter Becker and Raul Midón, and has racked up a long list of varied credits as a composer. Klein has written or co-written songs for many of the artists he’s produced, and has contributed to a number of film scores. His virtuosic musicianship, primarily as a bassist, has been utilized by Bob Dylan, Peter Gabriel, Randy Newman, Don Henley, Freddie Hubbard, Robbie Robertson, Neil Diamond, Warren Zevon and many others. “When I go from project to project, I’m always trying to learn something or discover a new way of doing things,” he says. “That’s what’s exciting and fun about making records. I want to work with those who have that same spirit.”

Although he’s as comfortable in a high-tech recording studio as any other producer, Klein in some ways remains proudly old-school. “In the wrong hands, someone using this stuff in a heavy-handed or a self-congratulatory way ends up making bland records,” he says. Klein still believes that a recording of lasting value is built on quality songwriting, superior musicianship and hard work. His productions are not about stringing together a collection of beats and throwing doctored vocals and manipulated sounds on top of them. For Larry Klein, a recording is not finished until he’s brought out the best that an artist has to offer. We caught up with him recently to discuss his philosophy about production.

How do you decide whether you want to work with an artist?

I listen either to the songs that the artist has for their new record or some of their previous work, and see what excites me. Then when I meet them, I try to get a sense of whether they are curious and want to do something different than they’ve done before. And I try to determine whether there’s openness, a basic humility there. Is this going to be a synergistic process, or am I going up against someone who is guarding their ego? If the person is incredibly talented but the other piece isn’t there, then I can pretty much surmise that making a record with them is going to be incredibly difficult, if not unsuccessful.

Do they usually know your work?

Quite often I get the sense that I’m meeting with someone who doesn’t really know anything I’ve done, or perhaps has heard one thing. That’s all right with me. I don’t need the stroking of someone saying, “I love what you do.” But it is super-important to have that sense of curiosity from a person.

How do you begin a project?

If I feel that they have a record’s worth of completed songs that are ready to go, which is very rare, then I would take a couple of days to sit and listen and think. Then I make what I call a flow chart. I’ll write out how I see the songs unfolding, who I would use to track them if it’s a live band situation, what instruments they would play, what they would play from section to section and what overdubs I would see doing. This is a fallback for me, a safety net, because quite often I’m juggling a few different things as well as being husband and father of a 2-year-old.

What is your production method?

I definitely don’t have a method. (laughs) I trust my intuition—and as happens with anybody in any profession, the more you do it, the better your intuition gets and the easier it is to produce the right way to solve structural problems. I panic less, but I always want a little panic. I think that’s good. I’ve come to know that it’s going to happen, that I’ll have one night of panic, almost always at the end when we’re working really long hours. I’ll usually have one day of thinking, “What is this? Is this really anything?”

Have you ever given up on a record that just wasn’t working?

No. It has happened where I’ve gotten a ways in a song and realized it’s not working. I listen to it on the way home and dream about how to do it the next day. Actually I’ll start working inadvertently while sleeping on how to approach the damn thing.

Does the musician in you ever conflict with the producer?

Each area feeds the other, they cross over and question and inform each other. I’ve been incredibly privileged to work with really talented writers. In the past, I’ve tried to direct myself toward making a hit, above making what I feel is a good record. Some are really good at that but I’m not. I’m comfortable looking at commerce now and then in the rearview mirror, but I’ve been lucky to be able to work on stuff that I love. I’m a bit spoiled that way.

Do you ever use a first take?

Oh, yeah. There are certain times when you just know. Sometimes about 10 seconds into a take, I’ll lean over to my engineer and say, “This is the one.”

How would you describe your approach to digital recording?

The use of the incredible editing abilities that we have now is a very delicate thing. Sometimes I’ll combine things from different takes, but I’m very selective about it. Whether it’s Auto-Tune, or being able to take parts of different takes and combine them, or the ability to time-correct things. There’s a great upside to all of this flexibility in that you can take something that has the right feeling—which is the most difficult thing to get—and you can correct a little structural problem, say an intonation thing, and still retain that great feeling.

Was transitioning from analog hard?

I held out for a long time, using tape machines, because I love the sound of tape compression and liked working with tape. But at a certain point they became pieces of furniture in the studio, and I had to face that reality. But what I do now is use analog compression and EQ. Almost everything I record is sent through analog gear to give it some blood and warmth and character.

How did you come to work with so many female artists?

It just happened that way. That was around the time I was married to Joni Mitchell. People’s perceptions are usually guided by very simple, overt things like that. Joni and I were working together on her records and having a great time, so people started approaching me about working with other female artists. At some point I met with my manager and said, “I really would like to work with some male bands or songwriters. People have put me in this box of working with female singer-songwriters.” And he looked into the distance and said, “That’s not such a bad box to be in.”

How do you prefer to record vocals?

When I’m working at my studio, I’ve found that doing the vocals in the control room is much more pleasant for everybody. When people are put into another room, there’s a certain kind of tone that creates an atmosphere of scrutiny. Usually we work on headphones.

What are some of the challenges?

I have had various things happen while creating the right situation for a person to sing and get to an un-self-conscious place. Once I couldn’t figure out why every time an artist sang a song it felt so different from the demo. Finally I said, “How did you do the demo? Where were you, how were you sitting or standing?” She said, “Actually, I was sitting in a chair and leaning over and had my elbows on my knees and a handheld [Shure SM] 57 in my hand so that I could operate the machine.” So what we did was recreate that posture, with a better mic. And sure enough, the act of sitting like that made her sing differently.

How crucial is post-production?

It’s equal in importance to me. By the time the tracking dates are over there’s usually a vague sketch of what I know will work in a beautiful way once the other work is done. So I’m projecting several steps ahead. Then comes the process of me working with the engineer, and the artist if they want to be there, and doing all the other work that follows.

What are you listening for?

In regard to editing and mixing, I’m listening to get the architecture of the track to work in the way that I see in my mind. In regard to vocal performances, I’m working to select the vocal material that touches me, makes me feel the lyric, makes me get goosebumps. When you hear a solo on a record that you grew up loving, it makes you feel a certain way. Music, when it’s done right, has this incredible emotional power.

Who would you still like to produce?

I’ve played with Bob Dylan, but I’d love to work with him on a record. I’d love to work with Björk, Don Henley and Leonard Cohen.

What’s next for you?

I’m just starting my own imprint with Universal Music Group. That’ll be a home for me to bring things that I want to do, hopefully a place that I can build something that reflects my sensibility and taste in music.

You’re starting a label in this climate?

I know! But that’s exactly the time to do it, when everybody else is jumping ship. It’s a challenge in this environment, but I feel if you make something really good, people are going to want to hear it. Maybe not millions and millions, but enough to make it worthwhile and profitable. If I can keep creating music that I love, then I’m happy.

comment closed