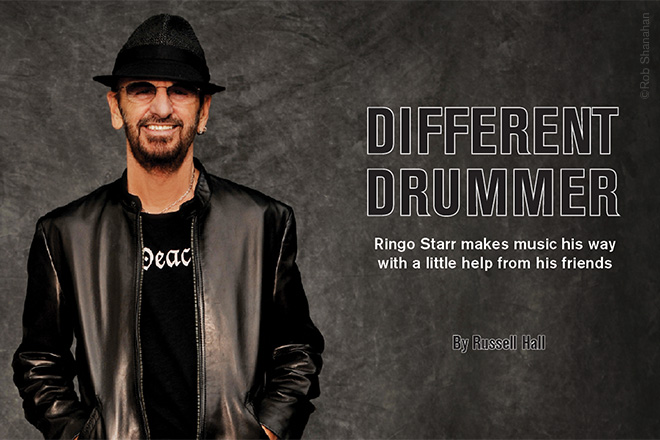

DIFFERENT DRUMMER

Ringo Starr makes music his way with a little help from his friends

By Russell Hall

Twenty-six years have passed since Ringo Starr was approached about staging his first solo tour. He still recalls his trepidation. “My immediate thought was, ‘What are you doing, saying yes?’” he remembers. “I didn’t have anybody to play with. So I opened my phonebook and started calling friends. We ended up with a great band.”

That simple philosophy—music is best made with friends—has been a recurring theme for the man born Richard Starkey. In the 1960s, of course, those friends happened to be members of the world’s most influential pop group. Besides being the Beatles’ gifted timekeeper, Starr was the band’s amiable center, a steady presence on whom John Lennon, Paul McCartney and George Harrison could always rely.

The drumming legend did storm out of a studio session—once. When he returned, he found his drum kit covered in flowers. “We worked hard,” says Starr, recalling his Fab Four years with profound understatement. “We didn’t sit around and say, ‘Let’s be famous.’ We only wanted to be musicians.”

Following the Beatles’ breakup in 1970, Lennon famously voiced concern about Starr’s future. He needn’t have worried. Starr hit the ground running as a solo artist in the early ’70s—“It Don’t Come Easy,” “Photograph” and “You’re Sixteen (You’re Beautiful and You’re Mine)” were among seven Starr hits that achieved Top 10 status. Once again, friendships were key. Ringo, his platinum-selling 1973 album, featured contributions from each of his former bandmates—as writers and as players. “I was friendly with everybody,” he recalls. “And it was easy. We knew each other. I went to George with my first real writing endeavors—‘It Don’t Come Easy,’ ‘Photograph’—because he was more into the production side. I just wanted to hit the drums.”

Starr’s spectacular success was marked by a period of decline beginning in the late ’70s as he struggled with alcohol abuse. A promising comeback album, 1981’s Stop and Smell the Roses,

was slated to feature two songs by Lennon, but in the wake of the legend’s death, Starr felt uncomfortable recording those compositions. The drummer kept busy with side projects, but his artistic skid didn’t end until 1988, when he and his wife, actress Barbara Bach, checked into a rehab facility.

Starr emerged a new man when the proposal to tour came the following year. “I hadn’t had a drink or drug in six months,” he recalls. “I was mad as a hatter.” Since then, Starr, 74, has enjoyed a steady stream of critically acclaimed albums and numerous touring stints with his famed All-Starr Band. The lineup—which has included Joe Walsh, Edgar Winter and Peter Frampton—tends to change every year or so. However the current band—Todd Rundgren, Steve Lukather (Toto), Gregg Rolie (Santana), and Gregg Bissonette (ELO)—has remained the same for three years, a testament to the group’s chemistry. “I’ve kept it together for three years because as personalities we get on so well,” says Starr. “I’ve had some

All-Starr Bands where two or three people get on, but there’s always somebody who doesn’t like anybody. This time I lucked out.”

Starr put that special camaraderie to use on his latest album, Postcards From Paradise. “Since the first All-Starr Band in 1989, I’ve wanted us all to sit around and write songs,” he explains. “I tried it with every band but it never worked until now.” The most collaborative song, “Island in the Sun,” grew out of a soundcheck. “Gregg Rolie started the ball rolling,” says Starr. “We all listened to it and tossed around ideas. After the tour everybody put their parts down at my little studio in my guesthouse.”

Other high points include “Touch and Go,” an infectious pop-rocker that recalls Starr’s ’70s hits; “Rory and the Hurricanes,” a fond remembrance of his pre-Beatles band; and “Bamboula,” a drum-heavy dance tune—written with Van Dyke Parks—that puts a British spin on New Orleans music. “For that one I played every drum I had in the studio, including three huge 100-year-old drums Joe Walsh sent me from Africa,” says Starr, who produced the album.

As with all of Starr’s albums, autobiography figures prominently, but never more so than on the title track, a playful tune that strings together titles of classic Beatles songs. Recently, Starr revisited some of those songs at the 2015 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame ceremony, where he was inducted as a solo artist, with McCartney doing the honors. “It’s been an incredible journey,” he said. From his L.A. home, Starr spoke with us about the new album, his creative process and the Beatles legacy.

Describe your writing method.

For the last three albums I’ve started out with a synthesizer, getting some rhythm patterns and establishing the key. I find something I like and then play drums to it. Once I’ve got that basic track, I begin thinking, “OK, I’ll play this part here. This part sounds like a verse. This other part sounds like a chorus.” I’ll do maybe a dozen, and call some songwriting friends and offer each of them the choice of two of those tracks to write a song to. I’ve got ideas, verses and sometimes just titles. That’s how it starts. It’s a mad way of working, but it works for me. The lead track, “Rory and the Hurricanes,” was the only one that was done differently. Dave Stewart and I wrote that one together from scratch. I gave him a synopsis of moments in my life, and he put it together musically. He played guitar and I played drums, and then we put everything else on.

Tell us about the exotic drums used on the song “Bamboula.”

That’s a good example of how I begin a song, where I just play along to a track. I started playing my English version of New Orleans style, and called Van Dyke Parks. Van Dyke is a music connoisseur—he knows everything about any music, from anywhere. He loved the track, and he told me about this drum—a bamboula—that’s made from giant bamboo. Once we got into the song, I decided I wanted it to be more of a street experience, like a New Orleans marching band. I have these drums that Joe Walsh picked up in Africa—huge conga drums that are around 100 years old. They sound really deep.

I added bongos, congas, and standard kits in no strict fashion at all—imagine 50 people in the street playing drums. I just faded it up, like they were approaching from four or five blocks away. And then we go into the actual song, and fade out, as if they’re passing by—sort of a Mardi Gras feel.

You got the All-Starrs in the studio.

That was a miracle. I’ve been trying for 25 years to get the All-Starrs to write and record together—and finally succeeded. Gregg Rolie started playing some riffs at a soundcheck, and we all joined in. It sounded like we were going somewhere. The next time we did a gig we worked on it some more. By the third soundcheck it had some form. Eventually we ended up in Biloxi, Miss., where I called the band into my hotel room and said, “Let’s write a song to that track.” Richard Page had written a couple of verses, I had written a verse, and Todd Rundgren had a verse. Warren Ham blew his sax and Gregg Bissonette played the steel drum. It sounded great.

The social aspect of making music seems especially important to you.

It is. The requirement for past All-Starr Band members has been that they’ve had hits. The other requirement is that we don’t torture each other, that we have fun and support each other. Some players from the past had the hits and did their jobs well, but there was no contact after we got offstage. This band hangs out together—the personalities gel. Of course we have some heated discussions—that’s life—but overall it’s a great situation I haven’t experienced in a long time.

How’d you develop your distinctive style?

Some of it has to do with being left-handed but playing a right-handed kit. It takes me maybe a nanosecond longer to get my left hand into the correct position to play with my right. My left hand is my dominant hand but it’s playing the snare, while my right hand is playing the ride and crash cymbals and everything else. So there’s that delay when I have to bring in the left hand. But the way I play also just came out of the atmosphere. It’s not as if I said, “I want to play in this style.” It was partly a result of not knowing how to play when I was starting out. When I first started, if you had a drum kit or a guitar, then you were in the band. We all learned how to play together.

There’s also a compositional aspect that rock drummers weren’t doing back then.

That’s right. Most drummers just played straight, whereas I played with the singer or the song. That’s my number one rule: The singer really doesn’t need a lot from me. I play the breaks and for the atmosphere. Sometimes things need to be brought down and other times they need to be kicked up, and I can do all that. But the main thing is, I play with the song in a way that other drummers weren’t doing.

Were you surprised by your early success as a solo artist?

Everyone was shocked that I had that No. 1 single and the big album with Ringo. You know how life is. Sometimes the moves just make themselves. I was doing the Grammys with Harry Nilsson, and he had worked with the producer Richard Perry—so I called him. If I had phoned another producer things might have been different. Richard did a great job, even though he drove us all crazy. If you look at those songs, they’re really like All-Starr records with lots of different artists. The Band was on it, George was of course, and John happened to be in town and had a song. It was an “of the moment, peace and love” record.

How did you create the All-Starr concept?

A promoter approached a friend of mine about a concept sponsored by Pepsi—and asked if I’d put a band together and go on tour. I had never thought of doing that. I started calling up friends—Dr. John, Billy Preston, Levon Helm, Joe Walsh, Rick Danko and Nils Lofgren. It was like an orchestra. Think it was the first and only time there were three drummers in the band: I’m in the middle, Levon’s on my right, and Jim Keltner is on my left. That was 1989. It was such a great experience I just kept doing it.

You’ve produced your last three albums. How do you see that role?

Like being a team captain. I had never produced before but things just came to a point where it made sense. The first album I produced was done the same way as Postcards. It’s all about collaborations, and I’m simply the one in charge. If there’s something I truly don’t like, I take it off. And if I like something, I play it for the musician I’m collaborating with to see if they agree. They usually say yes.

If proper stage monitors existed in the mid-’60s, would the Beatles have continued to perform live?

Yes. That was the drawback back then—we were working with the house PA, had no monitors, and didn’t have all the outboard gear that exists now. If we had had the technology to reproduce what we did on our albums—say, a song like “A Day in the Life”—the way we could now, there would have been a discussion about it, and I feel we may have carried on. We all loved performing. We didn’t get into music thinking we’re going to be at Shea Stadium one day. We just got into it thinking, “Let’s play.”

Thoughts on the Beatles’ legacy?

I just know I’m really proud of the music we made. I’m proud that it’s still being played and that it’s still relevant. The songs, the production and our playing are still as fresh as they were when we did it, in some weird and wild way. I look at that more than I think about the Beatlemania … I just think, “Man, we made a lot of great music.”

What drives you?

It comes from the same place as when I was in the Darktown Skiffle group, or with Rory Storm. My mother used to come to the gigs in the early days—including the Beatles gigs, when we played Liverpool. She would always say, “You know what, son? You’re always at your happiest when you’re playing your drums.” That’s true to this day. M

comment closed