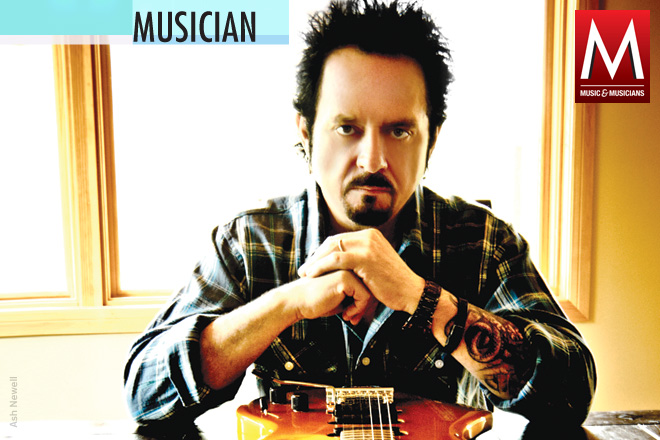

STEVE LUKATHER

Toto’s guitar giant steps out on his own with an emotional new album

By Russell Hall

Steve Lukather is feeling a little philosophical these days. The reason, he admits, is because he’s just come through an especially tumultuous year. “I’ve reassessed things,” says the veteran guitarist. “I stopped drinking and stopped smoking, and started going to therapy. It’s like the warranty is up at age 50. I have lots of friends who aren’t well due to the ridiculous things we did in our youth.” Lukather has earned the right to pause and take stock. The 53-year-old guitarist and singer has appeared as a session player on more than 1,000 albums, beginning when he was a teen. Paul McCartney, Elton John, Miles Davis and Michael Jackson are among the many major artists who’ve sought his services.

Still, he is best known for his work with Toto, the band he founded with a few high school friends in 1977 and saw blossom into a hit-making powerhouse over the following decade. The group sold more than 30 million albums during its lifetime as a recording unit, thanks to beloved singles like “Rosanna,” “Hold the Line” and “Africa.” Toto broke up in 2008, only to re-form for a tour in early 2010 to benefit bass player Mike Porcaro, who is suffering from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, or “Lou Gehrig’s disease”). The band’s most recent lineup includes Lukather, founding keyboardists David Paich and Steve Porcaro, singer Joseph Williams and drummer Simon Phillips. Toto has tour plans for 2011, although Lukather doubts the group will ever return to the studio.

In the late 1980s Lukather began staking out a successful solo career. His latest, All’s Well That Ends Well, showcases his playing in a dazzling array of styles, from the incendiary blues-rocker “Flash in the Pan” to the Beatles-esque ballad “Watching the World.” “You can hear all my influences in these songs,” says Lukather, whose solo tour begins in February. “I wanted to prove to myself that I could make a ‘personal best’ album, and I feel I’ve done that.” The California native spoke to us at home in Los Angeles about the new album, his session work and the future of Toto.

What was your goal for All’s Well?

I wrote nearly all the lyrics myself for the first time—and most of it is autobiographical, and painful. As a player and songwriter, I wanted to write melodic music with chord changes that weren’t clichéd. I wanted the chord changes to be interesting, but not go over people’s heads. I wanted people to shake their heads and go, “Wow, I didn’t expect that!” But I also didn’t want it to just be jazz-fusion wanking. I wanted to make music that’s not just for musicians, but have it still possess the craftsmanship that musicians would appreciate.

Was making the album cathartic?

It was—but I’m not alone in that. I just returned from a tour of Europe, and some of the people in the audience were singing along with every tune. People really feel these things I’m singing about. It’s a tough time for everybody. Matters of the heart are the same for everyone. We all bleed the same, and that’s what I’ve written about.

Do you believe session players get the respect they deserve?

The press hasn’t always been kind. Some hear my name, or hear the name Toto, and they immediately slam the door, so to speak. They think, “Ah, he’s just a studio musician. He’s not really important.” But I’m very proud to have been a studio musician. I remember meeting Jimmy Page [who got his start as a session player] for the first time. It was an event at the Guitar Center 20 years ago, and we were in a room full of other pro guitar players. He took me aside and said, “I want to tell you something. You see all these guys here? They’re not studio musicians, and they don’t know what that is. I used to do that. You should be very proud of that.” I nearly got a tear in my eye.

Toto was often critiqued as too slick.

I think it’s the stupidest thing in the world. Consider the world we live in now. There’s Auto-Tune, everything is done on computers and recordings are done one person at a time. When Toto recorded, we all played in the same room—together. People couldn’t accept that we were good enough to play in tune and in time. To be able to do that was considered slick and soulless. There was a rumor that went around that we were a manufactured band, a group put together by record company executives. That cracked me up. We were a real band, going back to high school. All the criticisms hurt our feelings, but at the same time, I would be willing to take them again. We had a successful career.

Do you ever write on keyboards?

Yes. I have a tendency to write ballad-y things on keyboards. It’s all right there. Put your hands down and you’ve got a whole orchestra at your fingertips. You’re not thinking about whether you’ve got a cool riff or a neat guitar lick. Writing at the piano creates a different mindset. The chords generate a different sort of melody in your head.

How important is rhythm guitar?

A lot of players try to jump from A to Z without going through the middle. They pick up a guitar and instantly want to shred. They build that facility, but then they’re not able to play with a drummer. Look at Jimi Hendrix or Eddie Van Halen—guys who are best known for their leads, but who are also fascinating, brilliant rhythm players.

Do you still practice?

I try to every day. Sometimes that consists of learning new music, or learning someone else’s music. That helps with ear training, among other things. Then there’s the technical aspect of practice, which might involve delving into Ted Greene’s Chord Chemistry book [1981], which one could spend a lifetime studying. Or I might turn to Nicolas Slonimsky’s Thesaurus of Scales and Melodic Patterns [1975], which can spark new ideas. I also listen to old bebop records. I’m not one of those guys who transcribes Charlie Parker solos or anything like that, but I do have fake books with his solos written out. For me a lot of practice consists of just listening to things. I’ll hear something and think, “Wow, that’s interesting. Let me try that.”

Do you have a home studio?

No. For years I’ve been doing all my recording work at an L.A. studio called the Steakhouse. They have a huge Neve desk console that used to be at EMI Studios in London. Dark Side of the Moon was recorded using some of those modules. I prefer old-school recording technology. I feel that’s the way it’s supposed to be done.

How would you describe your style?

I’m very chameleon-like, which goes back to all the session work I’ve done. I can tune in to whatever frequency is required. But within that, I’m still me. I still enjoy going out and playing guitar without trying to be the world’s coolest, fastest player. It allows me to work out a lot of angst. I see many young kids who have an amazing facility for the instrument but have no real passion. Subconsciously I’m still trying to compete in that world, but I am what I am. If someone likes what I do, that’s great—and if they don’t, that’s cool too.

What’s the status of Toto?

David Paich is retired. Steve Porcaro and Joseph Williams have successful careers writing for TV and film. Simon Phillips is happy in the jazz world. And I do what I do, which is tour the world and make my own albums. But we’ll get together and play live occasionally, doing a few weeks here and there for the right reasons. It still feels great to be standing on stage with people I went to high school with.

comment closed