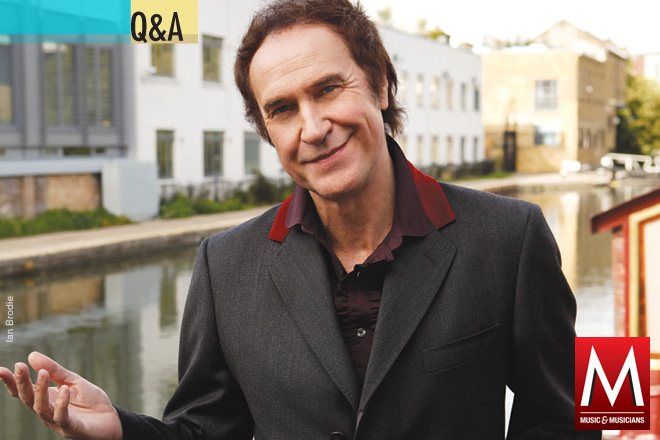

RAY DAVIES

Reinventing the Kinks catalogue with a roster of all-star friends

For almost a half-century Ray Davies has been rock’s own artful dodger. Slipping through pigeonholes and ducking stylistic dead ends, the native Londoner has always confounded easy labeling. With the Kinks he played the parts of white bluesman, vaudeville dandy, folk revivalist and heavy-metal screamer, penning wildly diverse classics like “You Really Got Me,” “Tired of Waiting for You,” “Lola” and “Come Dancing” all the while. Since the group’s ’90s dissolution he has carved out a new persona as a solo singer and songwriter.

But one role Davies never played was collaborator—until now. On the new See My Friends, the 66-year-old legend invites an all-star cast to join him in reinventing gems from the Kinks catalog. “The album came about almost by accident,” Davies says. “It was really a succession of chance events.” A one-off session with former Big Star singer Alex Chilton, a performance with Metallica at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame anniversary concerts and a backstage talk with Bruce Springsteen got Davies thinking about a different kind of duets record.

“It’s not just about covering the songs that are important to me,” he explains. “It’s about bringing a performance out of each artist—and the artists gave everything.” In addition to Springsteen (“Better Things”), Metallica (“You Really Got Me”) and Chilton (“’Til the End of the Day,” recorded a few months before Chilton’s death in March 2010), Davies recruited Mumford & Sons (“Days/This Time Tomorrow”), Lucinda Williams (“A Long Way From Home”), Jackson Browne (“Waterloo Sunset”), Billy Corgan (“Destroyer”) and other intriguing partners for See My Friends. We spoke with Davies about the new album, the magic of the ’60s and persistent rumors of a Kinks reunion.

How did you approach these songs?

We stripped them down to their basic arrangements and built them up again in a new way. The secret I learned early on with this record was to step back and let the various artists have their say. It was collaboration in the truest sense. I’d like to feel that all the songs could have been part of the artists’ respective repertoires. They certainly were not force-fed by me.

How was the Springsteen session?

It was like two old gunfighters. I went to Bruce’s studio in New Jersey and we spent about three hours talking and a half hour singing. I did my vocal live with him, face to face. What impressed me most—aside from his singing, of course—was his depth of knowledge of my music. “Better Things” [a relatively obscure cut from 1981’s Give the People What They Want] wasn’t an obvious choice. He also wanted to do a song of mine called “Art Lover,” which was not a hit. He was great. It was like talking to your friend down the block, two guys interested in music and guitars. He couldn’t believe I wrote “You Really Got Me” on the piano.

You did?

I wrote that really early on, when I was in art school. We listened to a lot of modern jazz back then. Art school was a great hotbed of different styles of music. There was a jazzy feel to the original riff. It was inspired by Charles Mingus, Miles Davis and musicians of that ilk. Later my brother [Kinks guitarist Dave Davies] played it with a distorted guitar sound and it became more of a rock riff.

Do you recall where you were when it reached No. 1 in the U.K.?

I spent that day on a train in the baggage compartment—because I didn’t have a seat—with an awful cold and a very runny nose.

What was the original inspiration for “Waterloo Sunset?”

I woke up one morning and it was there. Originally I wanted to call it “Liverpool Sunset,” but you know the advice for writers: Write what you know. I knew London better than I knew Liverpool. And [the London district of] Waterloo was a pivotal place in my life. As a kid, I was in hospital at Waterloo. Later I’d go past the station on the train when I went to art college. And I met my first girlfriend, Rasa, who became my first wife, along the embankment at Waterloo.

How did you create the characters in that lyric, Terry and Julie?

As soon as “Terry and Julie” came out, when I was singing it, it seemed that they didn’t need description. With records, I like to let the listener do some work and conjure up images their own way. If everybody could draw a picture of Terry and Julie, they’d all draw a different picture according to people they knew. I remember a moment with Jimi Hendrix when we were on [BBC TV series] Top of the Pops together. He was there doing “Purple Haze.” We met in the corridor and he said, “I love your tune.” He played “Waterloo Sunset,” just hammering the notes with his left hand, and it had that wonderful Hendrix feel.

What was the world like in 1964, the year the Kinks broke through?

It was the year pop music really landed on the world stage, saying that this is not just a passing phase but something that would make an indelible stamp on popular culture. I was born in 1944, but I was really born in 1964. The energy of the early ’60s was odd—it was like innocence coming onto center stage. Everyone was kind of clumsy and unprofessional. The Beatles were very professional, of course, but there was still a lot of innocence and naiveté to it. The moment it stopped being innocent it turned into a major industry.

What made the Kinks stand out from your peers?

The difference with the Kinks was that we experimented more than others. A record executive said to me once, “We love the band, but can you bring out two records in a row that sound the same?” The same band that did “Waterloo Sunset” did “You Really Got Me” and “Sunny Afternoon.” They’re so different in range and breadth. That may have irked some, because people like you to churn out things that are similar. Almost from the get-go the Kinks branched out and experimented—sometimes we had failures and sometimes we had hits. With those failures you tend to get a few points deducted. (laughs) I recently saw a YouTube clip of the Kinks covering Slim Harpo’s “Got Love if You Want It”—and what amazed me was how tight the band was. It was so good that it shocked me.

So, will the Kinks reunite?

I saw Dave last week, and he’s doing all right. But he lives in the West Country [in the English county of Devon], and he’s not keen on coming up to London. He doesn’t want to spend time in the studio. I met with [original Kinks drummer] Mick Avory earlier this week. We’re thinking of starting the tracks, then inviting Dave later. But if Dave doesn’t want to do it, and the tracks sound good, we might still pursue it. I don’t want to force anybody to do anything. The thing about the Kinks is that we have to do it because we enjoy it and because it’s in the spirit of the moment.

–Bill DeMain

comment closed