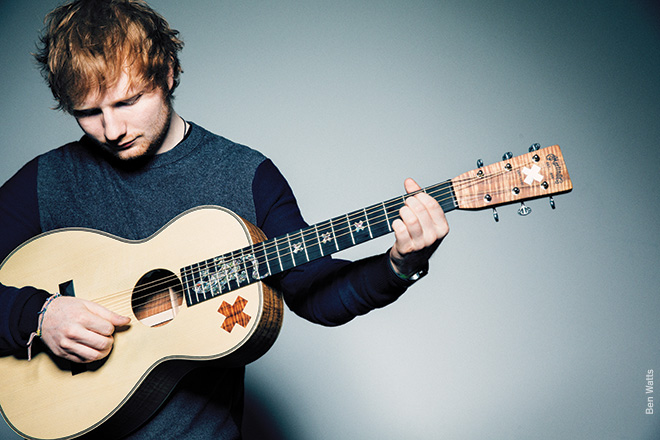

UNPLUGGED & ON FIRE

Ed Sheeran pushes acoustic boundaries to find new musical territory

He arrived on the mainstream music scene three years ago with a massively successful debut album of delicately crafted acoustic ballads. So it might have been understandable if the world had gotten used to thinking of Ed Sheeran as a laid-back, reliable balladeer. But the 23-year-old troubadour has since emerged as a pop phenom, a creative dynamo whose varied projects reflect unbridled energy that even he doesn’t seem to know how to tame. “I want to one day run out of steam and just chill,” he says. “I’d like to get to a point where you just reach a level and stay there—you know, how Springsteen never dropped from being Springsteen. But right now the spark’s definitely full flame.”

Sheeran grew up in the English hamlet of Framlingham—where his parents ran an art consultancy firm—and discovered that music provided a sense of direction. “I was a misguided kid,” recalls Sheeran, who penned his first song at 11. “I needed focus—and as soon as I started writing songs and playing shows, that became my focus.”

In his mid-teens, with his parents’ blessing, Sheeran dropped out of school, moved to London, began gigging relentlessly, and self-released a string of EPs. He moved to L.A. in 2010 and spent a year couch surfing and working open mic nights. He eventually landed a record deal and a management contract with Elton John’s Rocket Music. “The last EP I put out sold close to 10,000 in its first week, without a label,” he says. “So by the time I signed to Atlantic, I had a fan base that was buying CDs, and I had the radio expectancy.”

Sheeran’s years of tireless groundwork served him well in England, where his debut album, +, met with instant success. Powered by the singles “The A Team” and “Lego House,” the record achieved multiplatinum status and earned Sheeran two Brit Awards—the U.K. equivalent of Grammys—for Best British Male Solo Artist and British Breakthrough Act. America proved tougher to crack, but “The A Team”—a melancholy ballad about a doomed prostitute—burned slowly up the charts, eventually cracking the Top 20. “I’m still surprised radio played it,” says Sheeran. “Not everyone gets that tune, although rappers always did.”

Among those taking notice was Taylor Swift. After partnering with Sheeran to write the hit “Everything Has Changed,” on her smash album Red, the country star recruited the up-and-coming singer as opening act for her 2013 arena tour. “It’s a healthy relationship,” says Sheeran of his friendship with Swift. “We’re almost the same age and do the same sort of thing. Obviously she’s a lot more advanced in her career than I am.”

The exposure brought Sheeran legions of new fans, enabling him to sell out three consecutive solo shows at New York’s Madison Square Garden that same year. Three Grammy nominations quickly followed—including nods for Best New Artist and Song of the Year. He’s since written songs with pop singers Hilary Duff and Demi Lovato and acclaimed London soul singer Jessie Ware.

Sheeran’s latest, X (pronounced “multiply”), mines new terrain without sullying the singer’s reputation for lovelorn acoustic balladry. In addition to soundman Jake Gosling, who produced +, Sheeran tapped hit-makers Rick Rubin, Pharrell, Benny Blanco and Jeff Bhasker to helm various aspects of the record. “I listened to a lot more types of music prior to making this album,” he explains. “I expanded my musical palette, stepped outside my comfort zone.”

Among the most striking departures is the first single, “Sing.” Produced by Pharrell, the tune finds Sheeran strumming acoustic guitar to an infectious dance-pop beat. “I wanted to make something ‘Justin Timberlakey,’” he says, describing the song as a successful experiment. “Don’t”—a similarly groove-based dance track—was produced by Blanco and Rubin. “Together, I knew they would make something really super-powered,” says Sheeran.

Mostly, X uplifts and expands Sheeran’s status as a powerful and sensitive troubadour. Ballads like the somber “Photograph” and the beautifully majestic “Tenerife Sea” tug the heartstrings with soulful romanticism. “Until now I’ve been viewed as an acoustic balladeer who sings soppy love songs to teenage girls,” says Sheeran. “That’s something I’ve never shied away from, and it’s something I can do quite well. But this record is more of a step forward.” Sheeran discussed the new record, handling success, and what’s required to write a good love song.

What was your goal for the album?

It was largely about writing a bunch of songs and then selecting the best. I ended up with more than 100, and I made sure to listen to them every day. The ones I got sick of were taken off the list, and the ones left over eventually made the album. It was all about having good songs first, and production, second.

Did you plan on using various producers?

Not at all. The plan was to do it the same way we recorded the first album. I hadn’t yet broken through in America when we began, so there were no producers asking to work with me. As things got more successful in America, people like Rick Rubin and then Pharrell popped up.

At one stage, Rubin was slated to produce the entire album.

That’s right. I recorded most of the songs soon after I wrote them, and those recordings were carried forward with Rick. There were some demos where we kept the original layer. But when I did “Sing” with Pharrell, I felt that would have stuck out like a sore thumb on an entire Rubin-produced album. “Sing” was more of an experiment than anything else. I wanted to see what it was like to work on a song with Pharrell. We did three songs together, and two ended up on the album. But at the start I didn’t know we’d go in that direction.

Elton John and Taylor Swift insisted that “Sing” be chosen as the first single.

It wasn’t just Elton and Taylor. That was pretty much everyone’s choice. Obviously I ended up following their advice. Originally I felt “Sing” was meant for another project. Plus I had reservations because I couldn’t play it live by myself. It’s a very band-oriented song. The rest of the record I could do with the loop pedal. Since then I’ve worked out a way to play the song solo. But initially I thought, “I’m going to have to play this every day, everywhere—and I can’t do it alone.”

Compare Rubin and Pharrell.

In some ways their approaches are very similar: They know what they like and enjoy pushing boundaries. That said, Pharrell is more of a full-sounding producer—he likes a fat, beefy sound. Rick is more of a reducer. He removes everything that doesn’t need to be there, leaves the bare bones of the song and the performance. Rick is the reason the album became an album. Before he got involved, it was just a bunch of songs. He helped me with it both emotionally and musically.

Which song surprised you most?

“Afire Love.” It took a while to come together. It started off as just a beat with a hook, and then bit by bit the verses were finished over the course of a year. It was built in a very natural sort of way.

“Don’t” also came together in an unusual way.

I did a version with Benny Blanco, adding his pop sensibilities, and then I did a version with Rick that featured his unique sensibilities. I wanted to find a balance between the two. I really liked Benny’s drums but then I also liked Rick’s ideas—so we put them both in a room together. I had finished my recording, so they collaborated and sent it to me. I actually wasn’t there.

Do beat-oriented pop songs feel as natural as ballads?

The songs that come most naturally are the ones where I feel I’m getting something off my chest—storytelling, I suppose. “Sing” and “Don’t” are quite radio-friendly, but they also tell stories I felt needed to be told. Songs like “One” and “Afire Love” and “The Man” aren’t especially radio-friendly, but they do the same thing. As long as a song holds meaning and comes from the heart and soul, it doesn’t matter which side of the ledger it comes down on.

Do you always write on your Martin LX1E?

Not necessarily. I always write on guitar but I’ve written on Taylors and Lowdens as well. A song typically begins with an idea recorded to my phone. I stock them—sometimes for a long period of time—and eventually flesh them out.

How did you develop your stage act with an acoustic guitar and loop pedal? Had you seen others do that?

Not to this level. A guy named Gary Dunne, who I first saw as a support act for Nizlopi in 2005, was the first person I saw using a pedal. I always thought I would stop using it at some point, but I never did. The stage show evolved as I evolved.

Will it change as you play bigger arenas?

No, I have a niche. I stand out from the pack because I do the arena level with just the loop pedal. Having a band would be an unhealthy thing for me right now. After my music plateaus a bit, I’ll put together a band.

You surprised many when you sold out three consecutive shows at Madison Square Garden.

You can’t measure an artist’s success through record sales nowadays. That’s something I understood. The industry looked at me as someone who had sold 800,000 records. I saw everything else—the number of kids who were into the music, kids who don’t buy music but instead stream it or illegally download it. When you’ve sold 800,000 records, and you have a young fan base, you should probably add another 3 or

4 million to that figure. With that fan base you can fill an arena. People are more likely to pay to see a show than they are to buy an album.

Was your success in the U.S. surprising?

When I was first starting out in England there wasn’t as big a singer-songwriter scene. It had been years since Damien Rice or James Blunt or David Gray had released anything, so I slotted into that vacant space quite easily. In America, when I first came over there was John Mayer, Jason Mraz—those types of singer-songwriters. I wasn’t expecting to just come to America and slot in easily. That whole scene was already established.

Know a hit when you hear it?

No, I thought “The A Team” wouldn’t be a hit, and “Lego House” would be. “Lego House” was a hit in most countries but not in America. I can tell what a good song is, but I can’t tell you when a song is good for radio. I’m not sure anyone can, really—otherwise, people wouldn’t have songs that don’t work on radio.

You once said trying to please everyone is a certain path to failure.

That’s true. I have quite a young female fan base, and they like poppy love songs. I could have made an entire album of those songs. But spoon-feeding your audience is always a negative thing—they want quality and don’t want to be pandered to.

Do you require a muse to inspire love songs?

I think you can never be “in between.” Songs are born out of real emotion. You have to be drastically happy or drastically unhappy. If you have a muse who keeps you level and keeps you comfortable, you’re probably not going to write. If you’re with someone who makes you either extremely happy or extremely unhappy, that’s when songs will come.

Does that mean a life of drama?

No, most people who are famous for love songs tail off at some point. They get married and have kids and get comfortable in that situation. There’s nothing that pisses them off anymore. Actually that’s probably my future. I’ll join every other singer-songwriter who ever made pissed-off albums and then doesn’t make pissed-off music anymore.

Why do female artists want to work with you?

I’m not sure. (laughs) There are quite a few guys as well, but I don’t do male collaborations so much. I feel one man can sing a song just as well as two men can, especially in my genre. When you work with a female singer-songwriter you can do a variety of things. Those duets always sound different and interesting.

Has success been what you expected?

You hear lots of horror stories, but it’s not bad at all. Things people say lead you to believe it’s worse than it is. They’ve probably had a tougher time of it than I have. I haven’t been followed around by paparazzi or been closely scrutinized. You do get knocks against your confidence with bad reviews, but that’s no different from doing an exam and getting a bad grade. Actually it’s not even like that. It’s more like doing an exam and having someone grade it who doesn’t necessarily know the subject themselves.

What are the keys to sustaining a career?

Humility, constant evolution, and being open to new things.

I never want to just rehash old stuff. “Sing” is a good example. Doing that with Pharrell is something I never would have thought about, and yet it ended up furthering my career much more than I ever imagined.

Best advice you’ve received?

Nothing ventured, nothing gained. That was my Dad’s advice. I live by that on a day-to-day basis. M

BY RUSSEL HALL

comment closed