First published in 2015.

“I was born a rebel,” Tom Petty once sang, and he wasn’t kidding. As a certifiable legend of rock music who has sold tens of millions of albums and filled countless arenas, he still takes a passionate stand about the things he believes in.

Take the environment, for example. Standing at the plate glass window of his Malibu beach house, he points out a spot where several dolphins are about to appear. “You’ll see ’em break water between those two boats,” he says, and that’s just what they do. He was horrified by this summer’s enormous oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. “Doesn’t that piss you off?” he says. “It’s beyond belief.” And he puts his money where his mouth is—this cozy, cabin-style beach residence runs completely on solar power. “There’s no electric bill,” Petty notes with pride.

Or you can get him talking about the subject of rock bands who record with the aid of a metronomic click track to stay in time. “Hearing a mistake in a record today would make me happy,” he says. “I don’t like computer drums and things like that. Music wasn’t meant to be played that way. The human gives and takes in its rhythm. Maybe there’s not that many people around who want to practice anymore.”

Then there are the music business executives who used to complain to Petty, “I don’t hear a single,” as he noted in his 1991 hit “Into the Great Wide Open.” That’s something that did not concern him during the recording of Mojo, the 12th and latest studio album he has recorded with his backing band of almost 35 years, the Heartbreakers. “In those days, they always wanted a song that could promote the album,” he recalls of his period as a consistent Top 40 pop hitmaker, an impressive run that lasted from the 1970s well into the 1990s. Petty cranked out one radio favorite after another—with the Heartbreakers, as a solo act and as a member of his much-beloved supergroup, the Traveling Wilburys. “I did that all my life—go back and write another hit song for ’em,” he says. “And that was fun and great, but we’ve grown up and we don’t have to do it.”

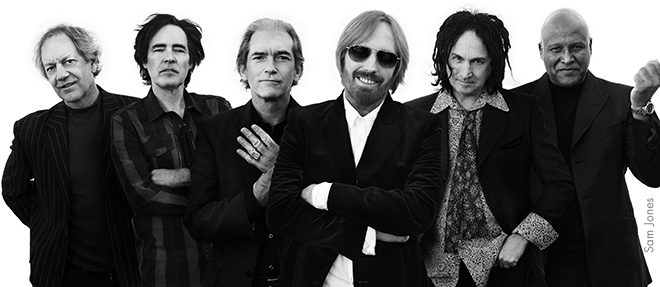

But the thing that really gets under his skin is the thought of succumbing to the temptations of nostalgia. Mind you, over the last few years it was easy to mistake Petty and his Heartbreakers—guitarist Mike Campbell, keyboardist Benmont Tench, bass player Ron Blair, multi-instrumentalist Scott Thurston and drummer Steve Ferrone—for a “classic rock” act. There was last year’s four-disc boxed set, The Live Anthology, culled from shows throughout the band’s career. There was 2007’s four-hour documentary, Runnin’ Down a Dream, directed by Peter Bogdanovich. There was 2006’s retrospective 30th anniversary tour, and the 2008 self-titled album by Mudcrutch, Petty’s reunited pre-Heartbreakers group (which also included Campbell and Tench). And there was the 2008 Super Bowl halftime performance, during which the group stuck strictly to hits from the 1970s and ’80s. “I think we’ve all had enough of that,” Petty says with a chuckle. “So this was probably the end of celebrating our past for a while. They were all satisfying projects. But what’s really interesting about this band is that it’s still as good or better than it was, and we’re still putting out good stuff.”

Which brings us to Mojo, the first Heartbreakers album since 2002’s poorly received The Last DJ. It’s a stripped-down effort for which the group eschewed overdubbing and actively avoided its own familiar musical signatures. “There were a couple of songs that we would start playing and we’d get halfway through and look at each other and go, ‘We’ve already covered this territory,’” Campbell says. “Because the Heartbreakers are so good, Tom can count a song off that we’ve never heard before and we can instantly make that sound like you hear on ‘Refugee’ or ‘American Girl.’ We do that instinctively. But we don’t want to repeat ourselves.” Instead, Petty and company elected to explore for the first time in the studio a style that they’ve been playing in rehearsal and in concert for many years. “The blues is paramount, and the Heartbreakers are particularly good at it,” he says. “That’s really where we have lived for a long time, off-camera. When we’re playing for us, that’s what we play.” But Petty is careful not to describe Mojo as a blues album. “It’s our warped way of making a blues record,” Petty says, “and it comes out as something completely different.”

On the album’s centerpiece track, the seven-minute “First Flash of Freedom,” Petty sings about the liberation of new experiences—both the discoveries of a younger person and the ongoing revelations of someone with a long and rich history, someone very much like himself. “I think there’s a constant comparison with things you first flashed on early in life,” says Petty, who will turn 60 on Oct. 20. “I think you often hold those experiences up to things later in life. Some people spend their whole life trying to get back to that. And then some people are wise enough to know that was then, and this is now.” We spoke with Petty about then, now and the challenges of running down a brand new dream.

What are your hopes for this record?

I’d like people to notice that we’re still doing things that are worth hearing. Very few can say that about a 35-year-old band. I want to keep moving. We’ve found a musical area where there’s a lot to be mined. These are good days for the Heartbreakers. We’re not looking back. All that was nice, but it’s essential that there be new things. I do not want to ever get in that situation of being only appreciated for your past. That’s not a good feeling. (laughs) This is a definite forward statement.

It’s a more lighthearted record than usual.

Lighthearted, yeah. Well, you don’t want to be real serious all the time. That really makes you a boring ass, doesn’t it? (laughs) Nothing worse than some musician being really serious.

You’ve certainly done very serious albums.

Yeah, and I was probably a boring ass. I don’t want to be too serious. I just want to be pure. I want it to move people rhythmically, provoke them mentally or just make them feel good. Mostly I’m trying to get a song done. If it feels good, I offer it to the band and say, “What do you think?”

How do you balance the group with solo projects?

My guys aren’t side musicians—they are a group. It’s always been about keeping these same people together and seeing what we can get out of it. At times I’ve had the urge to go away and make a record on my own. But [1994’s solo-credited] Wildflowers, for instance, I don’t think is really a solo record. It started as a solo record and ended up with all of them on it [except drummer Stan Lynch, who left the band later that year]. So I can’t get very far from them without wishing they were back. I still wouldn’t want to play with anybody else. They’re the band I want to be in.

How do you feel now about The Last DJ?

I don’t know that we were all happy with it in the end. I was being a bit more of a control freak with that album. In the studio, I’d come in with these really elaborate demos and say, “This is what I want.” And it was frustrating for them because they didn’t have much room to contribute a lot. They were mostly playing things that I had already sketched out. So I thought it really important in this record that we not do that.

What was recording Mojo like?

I’ve made a lot of production pieces, but I wanted something more immediate than that this time. No headphones, and we’d set up in a semicircle and work the songs up there. I didn’t make any demos. I just came in with my guitar and played it to them. If we came in at 2 in the afternoon, that track was done by 10 or 11.

Mike is very prominent on the record.

We wanted to get him up front and get the guitar right up loud—and he rose to the challenge. He tends to almost lay back, because he’s so tasteful and tuneful. I wanted to push him up forward and say “Look, get up there and rip, and don’t worry about it. The guitar is going to be the second voice of this record.” He used the same ’59 Les Paul through the whole record. I liked the sound of it real early on, and said, “Let’s just have the one guitar on this record for the lead guitar.” I like having a sound in there that becomes your friend throughout the album, like another voice. I did that on [2006’s Petty solo album] Highway Companion, too, where he only played slide guitar, and on Mudcrutch, where he used the pedal on the B-bender Telecaster. I’ve gotten more out of that idea on this record than I have on any of the other ones.

What were some of the other differences this time?

It was a lot of fun getting to play lead guitar. They let me play lead on “Running Man’s Bible.” And Scott Thurston’s guitar playing is really good, where he and Mike play together in “First Flash of Freedom.” That’s a really long piece and they had to rehearse and rehearse and rehearse, but they did it really beautifully. It’s an incredible thing. A lot of people have done the double guitars, and maybe that’s a little of the Duane Allman-Dickey Betts idea. We adored the Allman Brothers. I mean, long before they were in the Allman Brothers Band, from when they were the Escorts [Gregg and Duane Allman’s early-1960s group]. I watched Gregg and Duane play when I was a little kid. Also, one thing I don’t know if everyone’s picked up about Mojo is there’s not a single note of harmony in the whole album—something I did on purpose. It sounded too slick for the material. Now and then somebody would be sitting in the control room singing a harmony to something, and I’d go, “Ah, nope, can’t do it.”

Are you bothered if some fans don’t want to hear the new material live?

I have a feeling that they’ll stay in their seats and enjoy it, but I don’t give a damn if everyone goes to the bathroom. I couldn’t care less. I’m not going to be just a song-and-dance man. I’m gonna play what I want to play. I know I should always give people a good dose of what they came to hear, because I’m not playing at the corner bar, and it’s quite an effort to go into an arena and park and sit way up high and watch. But we also refuse to become one of these groups that only live in the past. I can come out and play two hours of hits and everyone will be happy and it’ll go great. But if I do that too much, I’m only feeding the nostalgia crowd. I love it when I see people and they play the hits, but I also want to see what they’re doing at the moment.

Songs never become classics if they aren’t played live.

If I had all this great new stuff in my back pocket and didn’t pull it out, it would be criminal. If we don’t do that, what are we? They’ve seen us play “American Girl” a hundred times. Golden oldies are great and it’s lots of fun, but it adds up to nothing if you’re not doing something new. I didn’t mind doing that on the 30th anniversary tour. I looked at it like, “OK, we’ll give ’em all the hits.” But I don’t feel that way now. It’s wonderful to have that kind of admiration and loyalty from the fans, but it’s also my job to keep the boat afloat and to keep exploring. If I’m going to keep myself engaged in this, it’s what I’ve got to do. There’s nothing wrong in being a “touring act.” But if you’re going to play the same material the rest of your life, it becomes a grim prospect. I’ve seen bands our age that gave up trying to create things. Maybe their heart’s really somewhere else and they’re working under a brand name so they can feed the babies. There’s nothing to be ashamed of in that. But it’s a lot more fun if you’re still creating and getting better. We’re all pretty well off. We don’t have to work if we don’t want. But we do want. M

comment closed