Road Scholar

Road Scholar

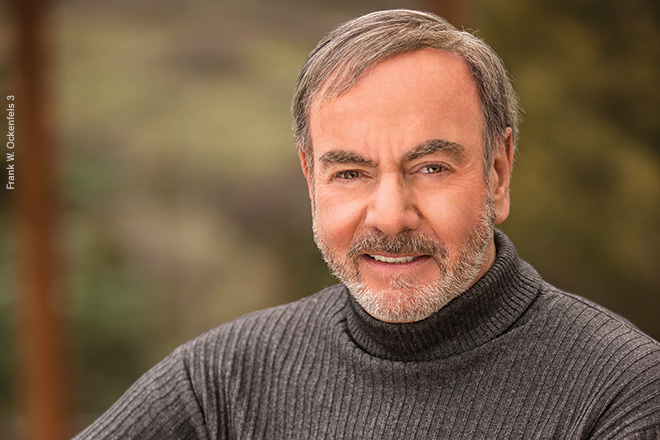

With his latest, Melody Road, pop legend Neil Diamond proves every song is a learning experience

Neil Diamond has been writing songs for 50 years, so you might think it comes easy. Not so. Although melodies spring forth almost magically—“If I have a natural gift, that’s it,” he says—lyrics remain his bane. “It’s grunt work, requiring huge amounts of patience, diligence and focus. It’s ditch-digging, and unfortunately the ditch I’m digging is inside me.”

But the effort has paid off handsomely. Diamond’s achievements are staggering: 17 Top 10 albums, 12 Top 10 singles, 13 Grammy nominations, and more than 125 million albums sold. In 2011, Diamond was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. That same year, he was honored by the prestigious Kennedy Center. “It used to surprise me, the way some of the songs would connect with people,” he says. “But after a while you realize you’re hitting on some pretty common themes. I’m not surprised anymore.”

Diamond’s songwriting efforts began in the mid-1950s. Growing up in Brooklyn he took guitar and piano lessons in his early teens, in part to overcome shyness. His fifth song, an Everly Brothers-style ballad titled “Blue Destiny,” marked a turning point. “It was about love lost,” he recalls, “pretty deep for a 16-year-old. But there was an emotional connection made—and it’s still that same connection I look for with every song.”

Diamond enrolled at New York University intent on entering the medical field—but music beckoned, and in his junior year he dropped out and landed a job as a staff songwriter on Tin Pan Alley for $50 a week. Success came in 1965 with a tune titled “Sunday and Me,” a Top 20 hit for Jay and the Americans. But it was a series of Diamond compositions recorded by the Monkees—especially the 1966 smash, “I’m a Believer”—that established him as a bona fide hit-maker. “By then I had seven years of professional writing under my belt,” he says. “Till then the songs hadn’t been very good. I hadn’t yet learned to put myself into the material.”

Putting himself into his material meant combining a singular gift for songwriting with an equally singular voice, resulting in a juggernaut of success. “Solitary Man,” “Song Sung Blue,” “I Am…I Said,” “Cracklin’ Rosie,” “Love on the Rocks,” “Sweet Caroline,” and “Kentucky Woman” are just a sampling of Diamond compositions that have become irreplaceable threads in the fabric of American music.

Even when record sales slowed in the late ’80s and early ’90s, the artist remained a dynamic performer, his sellout shows drawing legions of self-described “Diamond Heads.” And in the past decade, two stark records made with maverick producer Rick Rubin—2005’s 12 Songs and 2008’s Home Before Dark—have only further affirmed his relevance as a contemporary force.

Diamond’s latest, Melody Road, deftly blends the big, vibrant flavor of his best-known songs with the stripped down eloquence of his work with Rubin. Produced by Don Was and Jacknife Lee, the songs explore family, nostalgia and romance. Diamond, who married for the third time in 2012, spent 18 months writing and refining the material before entering the studio. No one, including his wife, was allowed to hear the songs until they were complete.

“There’s no better inspiration than being in love,” he muses. “It’s what you dream of as a creative person. I’m very strict with myself now, because I’m the only one who’s looking over my shoulder. Each song is a puzzle, and I stay with them as they make incremental advances toward completion.”

High points include “Something Blue,” a rollicking, exultant tune that captures the essence of newfound love, “Seongah and Jimmy,” a beautifully orchestrated celebration of marriage that doubles as a paean to Diamond’s native Brooklyn, and “Sunny Disposition,” an infectious slice of pop-rock that fully lives up to its title. Diamond leaves it to others to assess the album’s themes, but he’s hardly sanguine about the record’s place among his body of work.

“Whether it’s a positive or negative album I don’t know,” says Diamond, 74. “That’s up for interpretation. But I think it’s one of the best records I’ve made, certainly one of the top five or 10 albums of my career. There was a lot of digging involved, and I’m very satisfied with my singing. I hope people love it for years, but I’m not stopping to pat myself on the back. I’ll be onto the next album soon.”

Did you have a specific goal in mind?

I went into this record hoping to tell a story. That was basically it. Generally the stories are about my life—my experiences or observations or conclusions I’ve reached. The title track was really the jumping-off point. It set the boundaries and gave me an outline, a direction to proceed. From that point I started getting ideas for the songs together. Some of the ideas go back a ways, but all the songs are newly written.

What did Don Was and Jacknife Lee bring?

They brought in musicians they liked, people they had worked with before. They also collaborated with one another. It’s the first time I had worked that way—with two producers working on the same songs. They got along really well, found common areas to work in.

Did your previous work with Rick Rubin lead you to dig deep?

I always try to do that, dig deep into the heart of a song. And I try harder with every attempt at something like this. It’s an ongoing process, a developing process. Even after 50 years I still feel like a songwriter-in-training. It keeps me nervous, 24/7. Every song is different, an adventure, a leap into the unknown. I feel new to the process every time.

Do you bounce ideas off anyone?

Not really. Songwriting, for me, is almost completely solitary—unless I’m collaborating, which is a whole other ball of wax. I love collaboration—it’s fun, you have someone to complain to and talk to—but I haven’t felt the desire to do that in many years. These songs are all solitary endeavors. They’re all about digging inside myself and finding new things to say, or finding new ways to say old things.

Recall your first song?

I had a girlfriend whose birthday was coming up. I didn’t have any money, but of course I wanted to give her a gift. I had my guitar and knew enough to play a chord sequence—I had just learned to play an A-minor to go along with the C and F and G chords. That’s all I really needed back then. So I wrote a little something to her. I had no idea what I was doing, although I had always loved music and always loved to sing. There was no particular technique involved. It was a pretty shabby excuse for a song, but she seemed to like it. And after I did it once I began to think, “Can I do this again?” So I did.

What was the title?

“Hear Them Bells.” As I look back, it was basically about getting married. It was a little presumptuous of me, but I wasn’t thinking much about what it meant. I wasn’t trying to tell a story or ask for her hand or anything. It was just the first thing that came to mind, something I was able to shape into some kind of form and sing for her.

What made “Solitary Man” significant?

It made me think about the meaning of these songs I was writing. Before then I never felt the songs had anything to do with me. I thought of them as just words and music—things I put together. “Solitary Man” was my first record to chart. The obvious question became, “Are you a solitary man?” I laughed the question off for quite a while because I didn’t feel it was relevant. But of course it was very relevant. That song was a self-portrait within the music, but I didn’t recognize I was doing that for the first six months or so. I was just writing songs.

Did that discovery affect your approach?

Songs are reflections of the writer, even if that’s not always obvious. There’s emotional content that’s reflective of the person who’s creating the song. That question about “Solitary Man” stopped me in my tracks. I never saw myself as a solitary person. I was just your average guy. It made me think about who I was and how these songs related to me. That said, while I’m writing, I’m not thinking, “OK, this is about me and a girl I once dated.” It just comes out of my mouth and I put it down on paper. It’s only after I finish a song that I can think about it a bit, and identify parts that are me.

How does it feel when someone tells you a song changed their life?

It’s incredibly flattering. I feel good about the idea that I can have that sort of positive effect. But it’s really more than I can deal with. I can only say, “Thank you,” and then try and get onto the next song.

Still, it must be gratifying.

It is gratifying. All of this is gratifying. None of it was expected or anticipated, none of it was planned for or even dreamed of. The simple fact that people are interested makes the experience gratifying. It’s just that when I’m writing, I’m not paying attention to these things. I’m trying to express myself through music and lyrics. How these things develop and where they lead is an unknown quantity. It’s an amazing experience to get feedback from people who have been moved by a song, people who might want to know what I meant by a certain line. Usually I’m not sure what I meant. I’m paying attention to what it feels like, not what it means. I’m not acting in the role of a journalist. I’m acting as a poet or as an observer. The rest is up to the listener.

Do you have a go-to guitar?

I have three or four favorites. I’ll try one during the sessions—see how it works—and if it’s not working for me I’ll move on to another. I have a Gibson J series I bought a few years ago, an early ’50s acoustic I especially like. It’s got a wonderful sound for certain kinds of rhythmic things. And I have two or three Martin acoustics as well. One is quite small, a Martin my son lent me that’s more than 100 years old. I’m not sure of the model but it’s a wonderful guitar. I wrote most of the songs I did with Rick Rubin on that guitar. The fact that it was ancient made it even more interesting. The sound was different from any guitar I had played before.

How do you create a classic tune?

First, there’s luck. I would put that right at the top of the list. The process of taking a melodic idea, shaping it into a song and then getting it to the ears of the public, where people can hear it enough times to decide whether or not they like it—all of that involves an element of chance. Beyond that, it’s got to have heart and it’s got to say things people want to hear again and again. It also helps if it’s a little different from anything people have heard. But really, you have to be lucky. Just as we require some luck to live a long life, a song needs some luck to be born and survive into old age. People should never discount the value of luck in any endeavor.

Is it hard keeping old material fresh?

Not if the songs are good. Every time I perform it’s with a different audience, and I’m in a different frame of mind. Each time feels like an entirely different experience, entirely different circumstances. Of course the song has to have substance. You can’t go out and do jingles and expect to be moved. I’m genuinely turned on emotionally by my music. If a song doesn’t do that for me, then it goes out of the set. It’s imperative for me to be affected by what I’m singing. I can’t do it in an emotional vacuum.

How do you put together a set list?

I’m fortunate to have a big reservoir to draw from—lots of songs with a variety of emotional content. That offers lots of options. I can pull out any song I feel like doing and shape it so that it’s right for the performance. One of my favorite things about performing is the immediate response. An audience either likes something or they don’t—they’re either involved or they aren’t. By the time I finish a song onstage I know whether I’ll do it again. It’s survival of the fittest. Or I might decide to work on a song, shape it differently for live performance. The audience is boss. It’s up to them whether to accept a song. That’s the unspoken contract, whether I’m doing a show or making a record.

Do you think about your legacy?

Honestly I’ve been running so fast, and been so focused, I haven’t had a chance to sit back and pat myself on the back. I’m on to the next song. Life is short and it’s getting shorter. I don’t have time to dilly-dally around and congratulate myself. I’m lucky to still be making my life and career in music. That’s all I wanted to do from the beginning, and I succeeded. Maybe on my deathbed I’ll think about those things. I’ll have all my recordings around me and have them play on a loop, and go out in a very slow fade with a smile on my face. M

By Russell Hall

comment closed