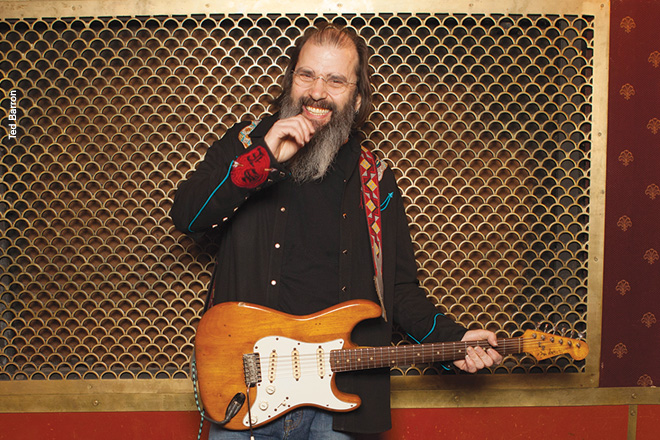

STEVE EARLE

STEVE EARLE

A powerful storyteller takes a hard look at hard times

“All singer-songwriters do this job on groundwork laid by Bob Dylan, who built his own fame based on Woody Guthrie,” says Steve Earle. “We’ve all done it with one foot in the 1930s, even though none of us—including Bob—witnessed that time firsthand. Times are really hard these days. What I’m seeing out the window is a lot closer to what Woody saw than it’s been in a long time, though I’m seeing it from a half-million-dollar tour bus rather than a boxcar.”

The view from that bus window served as inspiration for Earle’s 15th studio album, The Low Highway, a collection co-produced with Ray Kennedy that includes unflinching depictions of economic hardship, homelessness (“Invisible”) and the meth epidemic in rural America (“Calico County”), alongside songs written for HBO’s New Orleans–based drama Treme, on which Earle played a street musician.

In addition to being an actor and musician, Earle is also an accomplished prose writer, with multiple publications to his credit and more in the works. “I write every day, though not necessarily songs,” he says. “I write about stuff I feel needs to be written. I write mainly because it’s my job. I write because I believe it’s what I was put here to do, and I believe it’s disrespectful to the cosmos not to do what you were put here to do. A lot of people have a hard time figuring out what they’re here for. I don’t. I know why I’m here.”

How many songs did you start with?

I had 10 of the 12 songs written, and wrote two in the process of recording. Several songs were written for Treme, since that’s what occupied a lot of my time when I was writing for this record. I wrote two songs with Lucia Micarelli, who plays Annie on Treme. “After Mardi Gras” was a case of life imitating art and art imitating life. There was a storyline on the show where Harley, my character, is trying to convince her that she needs to learn how to write, because that will set her character apart from the other street performers in New Orleans and help her land a record deal. Lucia came up with a chord progression and the bare bones of a melody. I took that and wrote the melody and chorus. In the second season, you see Lucia sing it for the first time on the street. I wrote most of “Love’s Gonna Blow My Way,” but Lucia wrote the instrumental section in the middle that doesn’t have anything to do with the chord progression, which is sort of a classical thing to do.

What does Ray bring to this project?

Before The Low Highway, Ray and I hadn’t co-produced a record since The Revolution Starts Now, but we’ve done other projects together, and he mixed Townes. Ray’s especially good at what he does. When we work on my stuff, basically he’s the engineer and I’m the producer/arranger. He carries a lot of the water on the technical end.

What was the recording process like?

I wanted to make a record with my touring band the Dukes because they’re the best band I’ve ever had. We recorded in Nashville for five days and did nearly all of it live. The only overdubs are the organ part on “Pocket Full of Rain”—Allison [Moorer, Earle’s wife] left that day because our son John Henry wasn’t feeling well—and the backing vocals on “After Mardi Gras.” Everything else was recorded live. Ray started mixing the record after five days. I’m rarely present for mixing anymore—I trust Ray. Before mixing, we sit down, listen to everything, and I get my notes in. Then he mixes, and we can communicate on the internet. A lot of this record was mixed while I was on vacation in Florida. All the songs were pretty easy to record, we never struggled in the studio—though I struggled writing “Invisible.” I started it for I’ll Never Get Out of This World Alive but never could get it to hold together. I guess it just needed to be part of this group of songs. Thematically, “Invisible” has more to do with this record than the last, which was an inward-looking record. This is more outward-looking.

Seems “Calico County” is a jab at the redneck glorification in country?

Absolutely. Some people blame that redneck trend on me. All the people who heard “Copperhead Road” and didn’t get it blame that on me. It’s OK to be country, to be a redneck, but you can wallow in it to a point where it’ll hold you back. I’m trying to evolve. I don’t watch reality television. I don’t even watch Will Ferrell movies. I’m trying to become smarter.

“Remember Me” is a personal song.

It’s about me being old. I’m 58 and my son is 3—if I take really good care of myself and I’m lucky, I might see him through high school. That’s just the math. I felt the need to leave something behind, just in case.

How have you evolved in the 27 years since your debut, Guitar Town?

I’m still trying to say the same things now that I was then. I think I’m way better at it now. I’m a better singer, and that was mostly emphysema. I don’t have any records that I’m ashamed of, but I have a little trouble listening to my voice on the older stuff. This idea that the political records I made over the past few years are something new isn’t true. Copperhead Road was a political record. I was raised in the ’60s and ’70s and never thought there was any reason to separate art and politics. What I’m doing isn’t first and foremost pop music, it’s first and foremost art. The intention is to make art, and that goes hand in hand with politics.

I think the audience I have understands that connection between art and politics. There are some who thought they were seeing something else in me and were mistaken. Even critics thought I was some kind of neo-traditionalist country artist. They were disappointed I wasn’t, but I never told them I was. I used the word hillbilly and pissed off George Jones, God rest his soul. He said, “We spent all these years trying to keep from being called hillbillies, and Dwight Yoakam and Steve Earle screwed that up in 15 minutes.”

Guitar Town being a No. 1 country album still blows my mind. I’m very grateful for it since it was the beginning of my career, but I saw immediately that I was going to have to cultivate a different audience, because country radio wasn’t going to continue to support what I did. The single performance on Guitar Town was very spotty, and I saw that I was going to have to do something else. I was lucky I had a publishing deal. I made $85,000 a year just from publishing, so I could live on that and use the money I got from performances to pay the band, keep a cheap bus, and stay out on the road.

Any goals you want to achieve?

I’ve thought about writing a musical. I’m working on a memoir now that will probably come out early next year, and a novel that will come out about a year after that. I’ve got to finish a couple of other projects I’ve got on the front burners before I think about anything new.

–Juli Thanki

comment closed