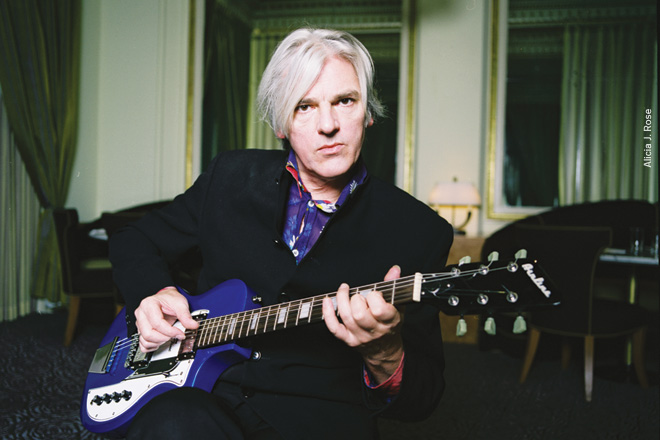

ROBYN HITCHCOCK

The enduring godfather of alt-rock is still full of sonic surprises

By Russell Hall

If Robyn Hitchcock never again hears the word “quirky,” that’ll be just fine with him. “I think what people mean is that, for me, an idea can come from anywhere,” he says. “They come from under the table, from behind the sofa, or from the back of a cupboard. They’re not the first places everybody looks. I suppose you could call that quirky, but I wish you wouldn’t.”

Imaginative is a more apt description of Hitchcock’s work over the past three decades. After making his mark with the Soft Boys, a band whose soaring jangle pop impacted the likes of R.E.M. and the Replacements, the Cambridge, England, native launched his solo career in the early ’80s and established himself as a college-radio favorite.

“People sometimes complain I cover up emotions by making a joke of things, but humor is what makes stuff bearable,” says Hitchcock. “Just because there are jokes in my material doesn’t mean I don’t fundamentally take it seriously. My favorite songs have different emotions layered on top of each other.”

Hitchcock, 60, certainly has a serious work ethic. Recent projects include recording with frequent collaborators the Venus 3 (R.E.M. alum Peter Buck, Scott McCaughey and Bill Rieflin) and staging intimate club performances of such classic albums as David Bowie’s Hunky Dory, the Beatles’ Abbey Road and Pink Floyd’s The Piper at the Gates of Dawn. “Rock ’n’ roll is an old man’s game now,” he says, “so I’m staying in it.”

For his latest album, Love From London, Hitchcock worked from the home of his longtime bassist Paul Noble—who produced the record—and recruited a tight-knit cast of backers to craft what he calls “paintings you can listen to.” During a stop in Manhattan, he spoke with us about the new record, his songwriting process, and why he doesn’t consider himself a quintessentially British pop musician.

How did you approach the record?

I played guitar and sang to a variety of rhythm tracks, and then Paul grafted the bass on afterward. Machinery being what it is today, you’ve got the sounds of Ocean Way, Abbey Road or Olympic Studios—all these legendary facilities—available at your fingertips. Jenny Adejayan came in to play cello, which gives the record a large part of its sound. Jenny Macro and Lucy Parnell did some vocals. Anne Lise Frøkedal sent her voice from Oslo, singing harmony on “Be Still” and “I Love You.” I didn’t even meet Lizzie Anstey, but she did harmonies on “Fix You” and played keyboard on “Stupefied.” We worked in a little room with the curtains drawn. There was only space enough for three people at once. One of the pluses of technological development: Fewer people are buying records, but at least you can make them more cheaply.

Was the material already written?

Some of it was. The first song we recorded was “Harry’s Song,” which opens the album. It pointed the way, especially with regard to establishing we didn’t need live drums. The drums were all computer-generated. Paul created his dream drummer. As the recording developed, I wrote more songs that I felt would work well with what I had already written.

Did a theme emerge?

That’s always interesting. Themes are never conscious. I don’t think you can steer your own conscious. Your conscious is there to steer you. It’s sort of a kind record, I suppose—hence the title, Love From London. As you get older you wish evil on fewer and fewer people, unless you’ve had a particularly shitty life. People tend to become either mellower or more bitter.

What’s your songwriting process?

I just pick up the guitar or walk to the piano and start playing. If there’s something there, you nurture it. It’s like bringing up a small animal. You feed it, water it, keep it clean and get it to behave properly. When it’s ready, you let it go. But you need the embryo. And once you’ve got that, the essence, you might spend six to nine months developing it. The gestation period is long, but the conception is instantaneous. And sometimes you just have to abort, because there’s not enough there to bring a song to birth.

How about your sense of melody?

I had no sense of melody to begin with. I used to try to make up songs as a teenager and couldn’t do it. It evolved. I was influenced by all the Beatles. I spent five years wanting to be Syd Barrett and 30 wanting to be Bryan Ferry. Ferry has a very strong sense of melody. His voice is like a handkerchief, whereas my voice is much more heavy-footed.

What drove you to write songs?

I never really wanted to do anything else once I dropped out of art school. It took me a long time to work out how it’s done. I started to write when I was 15 but didn’t write anything good until I was 25. Some people pick it up very fast. Apparently Syd Barrett wrote everything he did in the span of six months to a year and then he fell apart. He peaked very early. Dylan and the Beatles were writing some of their best material when they were 22. Ferry and Bowie, on the other hand, took a while to get going.

What’s your go-to guitar?

The rockers, the songs with the more overdriven sound, were written on an old Spanish nylon-string guitar. Writing on that guitar gives the songs a more bass-heavy approach. When I play steel-string acoustic—Fyldes, mostly—I tend to go for a trebly, wire-between-the-ears kind of spangle.

For live performance?

I have Sennheiser lapel mics in my two Fylde acoustics. Fylde kindly made me a new copy of my veteran Olivia guitar. The Olivia has been to the doctor even more than I have over the years, and needs to retire from touring. The Sennheiser captures the actual sound of an acoustic guitar, as opposed to making it sound like a weedy electric, which other mics seem to do. I keep the level down so that it doesn’t feed back into the monitors. As long as the audience can hear the guitar, it doesn’t matter too much whether I can hear it.

What’s the attraction of performing albums in their entirety?

Our generation grew up not knowing much about Mahler’s Fifth Symphony or Beethoven’s Ninth, but we do know all there is to know about Sgt. Pepper’s and Hunky Dory. Even while John Lennon was alive, the Bootleg Beatles tribute band was a popular draw. Now, half a lifetime later, tribute bands perform the best-known works of defunct rock acts, and rock acts who are still functioning are out playing their masterworks. Like classical music, rock now has a menu. People know what they’re going to get, they feel safe with it and enjoy it. I’ve enjoyed doing all those full-album performances. I have never seen a happier troupe of musicians than when we performed Hunky Dory.

Do you see yourself as part of a distinctly British pop tradition?

No, I don’t. I think Britain and America merge in one beautiful way, and that’s with music. I see rock as an Anglo-American tradition. Rock ’n’ roll started in America, but since the British Invasion around ’64 it’s been evenly divided. It’s since spread throughout the world, but Britain and the States pretty much spearheaded it. I’m from Britain, but I’m at least as influenced by American artists as I am the British—and all the British artists I like were also influenced by Americans. I dare say I come at it through a British filter, but no, I don’t see myself as a quintessentially British songwriter.

comment closed