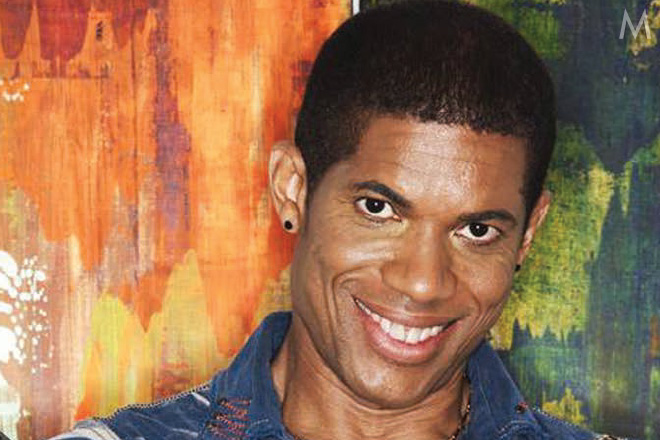

STANLEY JORDAN

STANLEY JORDAN

Still reinventing the sound of jazz, with the aid of some talented friends

By Jeff Tamarkin

“To me, I’m just playing guitar,” says Stanley Jordan. “Then somebody points out the technique and I remember, ‘Yeah, it’s weird.’” Most musicians would be loath to describe their own performance method as “weird.” But Jordan, who first astonished the jazz world more than a quarter-century ago, is well aware that his trademark approach is unconventional. His two-handed touch style, tapping the strings as if playing piano, allows Jordan to play melody, chordal harmonies and a bassline at once—or even to play two different guitars, or guitar and piano, simultaneously.

“When I released my first album on Blue Note, Magic Touch, in 1985, I made a conscious decision to focus on the technique from a marketing standpoint,” the Chicago native recalls. “There’s a fragility and an honesty to it that’s engaging. I don’t think anyone can dispute that it brings new possibilities, and that’s why I got into it. But by now I’m so beyond thinking about the novelty aspect.”

As he should be: Jordan is indisputably one of the most impressive guitarists in jazz, a point reaffirmed on his latest album, Friends. It’s the follow-up to 2008’s State of Nature, which marked his return to recording (and to the piano, which he learned as a child) after a lengthy hiatus during which he studied music therapy. For Friends, Jordan tapped world-class musicians including fellow guitarists Charlie Hunter, Mike Stern, Russell Malone and Bucky Pizzarelli; saxophonists Kenny Garrett and Ronnie Laws; trumpeter Nicholas Payton; violinist Regina Carter; bassists Charnett Moffett and Christian McBride; and drummer Kenwood Dennard.

This talented crew took on a set featuring original songs and interpretations of material associated with everyone from Béla Bartók and Claude Debussy to John Coltrane to Katy Perry. “When I think about the album, I think about the sessions,” says Jordan. He spoke to us from his home in Sedona, Ariz.

How did Friends come about?

In a way the album created itself—all I had to do was pick the people and give them leeway to decide what we were going to do creatively. I wish I could take more credit than that. When I made my dream-team list, those on it were almost exactly who I got. Every song is special and every artist was chosen for a special reason. Most of them I know and had played with, while others I knew from their music.

Why make a collaborative record?

When I did State of Nature it was kind of a return, so I wanted to do something where I was more the focus. State of Nature was a concept album about the natural world, and I wanted total control over what that would be. I feel the album accomplished that, so now it was, “I’m back, what do I want to do?” I’d wanted to do a collaboration project for a long time and decided the time was right.

How did you choose the covers?

A lot of it came from the selection of people on the album. From the beginning I wanted to do [Coltrane’s] “Giant Steps” with Mike Stern. The reason I picked that song was because Mike and I jammed on it in a hotel somewhere on the road and I thought, “This guy is amazing!” It’s a difficult song and he glides through it with ease. For Bucky Pizzarelli, I suggested [Charlie Christian and Benny Goodman’s] “Seven Come Eleven” and he loved that idea. He chose [Neal Hefti’s] “Li’l Darlin’.”

What’s your philosophy about recording an album?

Aristotle said that a work of art should have unity. If you’re going to make an album, it’s a unified work of art. I want something people can listen to from beginning to end. Also, I was brought up on all the great rock concept albums, so I like the idea that an album can be about something and make a statement. I go in with a concept. While things might change, I find if I keep that concept in mind I can make all those little decisions along the way.

How did you learn to play guitar and piano at the same time?

Pianists already split their brains between hands. If I want to play two rhythms at once, and I think about the two rhythms separately that might be more difficult. Basically, there are three possibilities: left hand, right hand or both. So there’s some sequence of those three possibilities. Once I’m playing the two rhythms, I can think about it differently and then notice that it’s two different rhythms. It comes down to doing it in slow motion—you can do almost anything if you slow it down enough. Right now I’m working on a three-part fugue from Bach’s The Musical Offering. The only way I can play it is if I sing a part and play the other two. So I’ll sing the low parts, play the middle part on guitar and the high part on piano. That way I’ll get the best tonal blend and be able to do all three parts while still doing it as a solo piece. When I play guitar and piano simultaneously, it’s like a super instrument: The guitar and piano become one instrument with a broad range of tonal possibilities.

How have you applied your digital music education to your records?

It’s the main aspect of my music that has been underrepresented. I’ve never felt compelled to prove what I know. I’m a harmony junkie—my basic vocabulary has over a thousand scales that can be played in all 12 keys. Maybe at some point I’ll do something where I feature that, but I find that most of the time it ends up clouding the music. There has to be a musical reason. The best example of it is “Asteroids” on the Cornucopia album [1990]—before State of Nature it was the only song I’d ever recorded that had no guitar. When I go to a dance club I’m amazed at all these wonderful electronic instruments, and so often they’re used in such a pedestrian way. It’s monotonous, like I’m being brainwashed. You’ve got the compelling rhythm, but harmonically there’s so much more you can do.

How did you learn your signature

touch technique?

I had a definite goal in mind. I wasn’t playing piano at the time, because my family had gone through tough times economically and we had to sell it. That’s when I took up the guitar. I played conventional picking and fingerstyles for six years, but I had all of this piano-istic stuff in my head. I love counterpoint, the variety of textures and the complex voicings pianos can do. I wanted a way to bring some of the piano texture to the expressiveness of the guitar. I finally figured out that if I did hammer-ons and pull-offs it wasn’t so difficult. I love that beautiful, delicate, sparkling, crystal-clear sound.

What are some of the challenges?

It’s not very forgiving. It’s like violin, in that you’re very sensitive to little things like the height of the strings and the temperature. If it’s not adjusted right, my fingers hurt. It feels like I’m banging my fingers on metal. I can be having a bad day, and it occurs to me that my strings are just a couple thousandths of an inch too high.

Was it hard to master?

I’ve spent so much time convincing myself that it’s easy, but I’ve learned through the years that it’s really not. If it were easier, more people would be doing it. But it’s opened up a world of possibilities to me, and I’d like others to experience that. I’m planning on putting together an educational website with interactive online courses.

Does it ever overshadow the music?

It’s all in the ear of the beholder. It was something to get people’s attention, but I also wanted to have a little more stylistic variety than your average recording artist. I’ve been told, “It can’t be done, you can only play one style of music, the industry isn’t ready for a multistylist.” So I decided to focus on a technique that gave me more leeway to explore different styles. I can understand why people focus on the technique—but for me, it’s all about the music.

comment closed