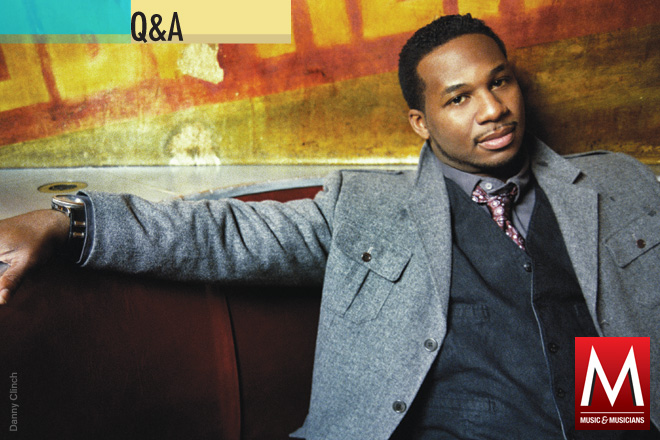

ROBERT RANDOLPH

Taking the pedal steel guitar on a journey into the past

By Chris Neal

As a kid, Robert Randolph’s life revolved around the House of God church in Orange, N.J. And as a member of a strongly religious family, he was forbidden to listen to secular music. “The thing is, I did listen to secular music,” he says with a chuckle. “I grew up in church, but we lived in the inner city. We’d play our church music, but we would sneak and listen to R&B and hip-hop music in those days.”

Still, Randolph’s musical education was mostly limited to gospel music. Even as he emerged from the church’s “sacred steel” tradition in the early 2000s (see sidebar) and established himself as a musical force in the outside world, he was conscious that his experience with popular music extended no farther back than the1970s. A couple of years ago he undertook to correct that oversight once and for all. He and his Family Band—bass player Danyel Morgan and drummer Marcus Randolph, both Randolph’s cousins—were ready for a break after seven years on the road, and Randolph took the opportunity to immerse himself in the last hundred years of African-American music. He listened to countless songs, with producer T Bone Burnett as his guide through the past. “Just talking to him opened up my musical dream to a whole other universe,” Randolph says.

The result is Randolph’s third studio album with the Family Band, We Walk This Road. The songs encompass sources ranging from Blind Willie Johnson to John Lennon and Prince, all filtered through Randolph’s own distinctive blend of rock, gospel, blues and R&B. Burnett and Randolph sought advice from friends like Robbie Robertson and former Warner Bros. Records president Lenny Waronker (the latter suggested that Randolph take on the little-known Prince gem “Walk Don’t Walk”), and brought in guests like Ben Harper, Leon Russell and master drummer Jim Keltner. “I’m glad I got the opportunity to talk to these guys,” he says, “because most people don’t.” We got the opportunity to talk to Robert Randolph during a break from tour rehearsals in New Jersey.

What did T Bone bring to the record?

T Bone is such a musical historian. He listens to the old, original stuff. He would be listening to what Jimi Hendrix listened to—Blind Willie Johnson, Howlin’ Wolf, all those dudes. In the South you had this blues stuff happening, and at the same time these guys came out of the church. They were just on the darker side. My grandma had stories about growing up listening to that.

Is there a fine line between gospel and blues?

Early on, it was really all the same. Gospel is the good word, blues is feeling down and out—but it was all the same chord patterns. These guys rebelled against gospel, went to the juke joints and played blues and talked about the down things. “I’m feeling down, I’m feeling blue.” It’s the total opposite of what the Southern Gospel churches were doing in those days. But if you listen to the chords, they’re the same. That’s where Ray Charles got his stuff. It’s funny, Ray Charles took many songs from gospel—it’s literally the same song, he just changed the words. I grew up in church playing those songs.

How did Ben Harper get involved?

We had played the Blind Willie Johnson version of “If I Had My Way,” and that turned into a long jam that we kept trying to write to. I was texting Ben the whole time, saying, “Hey, man, we’re right down the street from your house! Are you in town?” One day he came down about 10:30 at night and we started jamming on this instrumental thing. In the middle of a break he said, “Let me hear some other stuff that you might not have finished.” We played the Blind Willie Johnson thing, and Ben’s eyes lit up. He immediately went into the vocal booth and did those choruses in about 10 minutes. We sat down with T Bone and [songwriter] Tonio K. and wrote all the verses to it, and we finally had this thing. It’s a song we’ll be singing for the next 20 years.

Do you always write through jamming?

It’s either-or for me. Sometimes if we’re at a soundcheck, somebody will do something and a melody or a chorus will come to me and we’ll build off that. Sometimes I’ll just play and record myself. I may have a melody in mind, but I don’t ever write lyrics until I’m either on a plane or in a car. It’s the weirdest thing.

How did Leon Russell come to be on the record?

Leon had a meeting with T Bone the morning that we were finishing up the song “Back to the Wall.” T Bone mentioned he was working with me in the studio and Leon said, “Really? I want to come down and meet him.” So he came down and sat in the session while we were recording. We moved on to the next tune, and I said, “Hey, if you ain’t doing nothing you might as well come on and play this tune with us.” He was like, “Yeah!” It turned out to be this beautiful song.

How did you find the Prince song?

Lenny Waronker and Mo Ostin ran Warner Bros. when Prince and Ry Cooder and all those guys were around. Lenny had been out of the music for a while, but he and T Bone are buddies. T Bone said, “Hey, why don’t you come hang and help me work on this Robert Randolph record?” Lenny and I talked about all these songs—songs I’d written, songs he had. He said, “You know, there’s this one old Prince song that fits you and the Family Band. A lot of people don’t even know it. Most people probably couldn’t record it—but you guys, this is what you stand for. The message is there, the vibe is there. It could be really electrifying.” I listened to it and said, “Let’s try and do it.”

How about John Lennon’s “I Don’t Wanna Be a Soldier Mama”?

At the time when we were making the album, we would sit and watch the presidential debates and listen to the news about what was happening with Wall Street. All the lyrics on the album had something to do with what was going on—we wanted to uplift people. T Bone came across that Lennon tune and I said, “Let’s record it.” We went ahead and did it because it spoke to what’s going on in the world today. Even though Lennon’s version was probably meant to be anti-, we didn’t want our version to be anti-, even though we’re singing the same lyrics. It was more like, everybody’s tired of all this stuff. I’ve got three cousins over there in the Air Force right now. When you speak to them, it’s like, “We’re fighting, we want to win, but at the same time we want to come home.” So it is what it is.

What instruments did you play?

I wound up using a Weissenborn on the song “Don’t Change,” as well as a 1956 Fender lap steel. There were four different pedal steels that I used. There was a lot going on.

How about amps?

Fender just put out this new Bassman. It’s 300 watts and has a 15-inch speaker in it. I use that one now.

Do you often play regular guitar?

I played a little in the last couple of years I was in church. I started out playing steel guitar first. Being that a regular guitar is just so much more mobile, when you’re traveling on tour buses for hours and hours year after year, it becomes something you pick up every day.

What did you take away from the recording experience?

Making this record, there were years spent with T Bone and Lenny Waronker, months spent with guys like Jim Keltner. Talking to Robbie Robertson every day, being friends with Eric Clapton. If you go, “Hey, man, this sounds like a radio tune!” those guys will say, “What’s that? We just write and record songs because they feel good. It’s not about radio or MTV.” I had that constantly plowed into my head. I learned that you just work on something until it gets great, and people will learn to love and appreciate that. Elton John is sitting there looking at me saying, “What the hell is this? Where has this been all my life?” That kind of stuff. Those guys are like, “Gee, where did you come from?”

Do you have a goal in mind?

The goal is to keep recording, keep making music. You can only do what you feel, which is this thing that people fell in love with from the beginning. As long as you stay true to yourself and keep that thing going, that’s what will make our legacy grow. People will hear something someday and say, “Hey, that sounds like Robert Randolph.” Some kid who’s 8 years old will hear this and his musical brain will take him into another thing. That’s what will keep music going.

comment closed