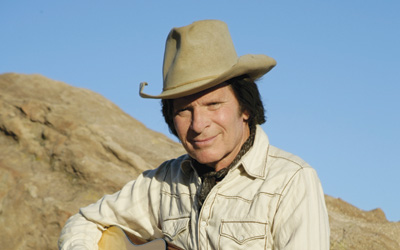

John Fogerty

The legendary rocker returns to his childhood influences

When Creedence Clearwater Revival split in 1973, lead singer and songwriter John Fogerty was determined that his first solo album would succeed or fail on its own merits rather than his famous name. So he invented the Blue Ridge Rangers.

When Creedence Clearwater Revival split in 1973, lead singer and songwriter John Fogerty was determined that his first solo album would succeed or fail on its own merits rather than his famous name. So he invented the Blue Ridge Rangers.

“It was a personal, ethical, moral issue,” he recalls. “I didn’t want to trade on that popularity. It’s probably suicide for a career, but I felt very strongly about not calling myself ‘John “Creedence” Fogerty’ or something like that. I created this fictitious band.”

The Blue Ridge Rangers album found Fogerty exploring traditional country music—a passion since childhood. “It was a time to reveal my influences,” says the San Francisco native. “What I presented was a balance of all the wonderful things that influenced me, that made me the person I was in 1973. I was still a very young man when I had this huge career with Creedence Clearwater Revival and made my mark on rock ’n’ roll. It seemed like the perfect time to go into the world that was so precious to me.”

His most recent album finds him revisiting that place after more than three decades away. While the first Blue Ridge Rangers album featured Fogerty playing all the instruments, on The Blue Ridge Rangers Rides Again he leads a stellar band of top-shelf acoustic players through a lively set of country covers. Fogerty has also just released a live DVD, Comin’ Down the Road, and he’s at work writing songs for a new album of original material.

We spoke with the Rock and Roll Hall of Famer about his evolution as a guitarist, his return to the Blue Ridge Rangers and the ups and downs of being a one-man band.

How did you first hear country music?

As a child, it just filtered in through the air. When I was young we had a little show in the Bay Area called The Hoffman Hayride. It was something that my parents watched as soon as we got a television, and I really enjoyed that. It was live, and people were spontaneous, and of course they played country music. We also got the Grand Ole Opry on TV when I was a kid. As a very little boy, I certainly was watching all the cowboy bands—Roy Rogers and Sons of the Pioneers and all that. They were a big influence on me.

Why did you decide to play all the instruments yourself on the first Blue Ridge Rangers album?

I discovered I was under this horrendous contract to Fantasy Records. Even though the band had broken up, I still owed them an enormous, unfair amount of product. So I decided to be a one-man band. I can’t answer fully what spasm of mental cruelty made me do that. It’s just too bizarre to me now. Let’s just say that I certainly was not completely healthy mentally. I don’t mean that I was running around like a psycho, but there was some obvious injury to my mental state. And that’s how it came out. I said, “Well, OK, I’ll be a one-man band. And I’ll be anonymous!” (laughs) It meant I had a lot of healing to do but I didn’t know any of that then. It’s hard to do a one-man band, man. There’s a lot of focus there. It’s like time-lapse photography watching a rose bloom all day long. And when the album was done I was having a meeting with one of the henchmen of Fantasy. The guy let me know I had this big obligation of albums I had to give him, and he said, “Well, we’re not going to count this Blue Ridge Rangers album as part of your obligation.” My jaw dropped. I said, “What do you mean?” He said, “Well, it’s country, and that’s not what we want.”

Given all that, it’s interesting that you continued with the one-man band approach on the next two albums, John Fogerty and Centerfield.

You might say I fell into purgatory at that point. I was also still in this contract, so I kept working at that method while I was trying to figure out some legal way out of that purgatory. I called it a dungeon, really—it had me chained to a wall. Finally, when Centerfield was realized in 1985, I figured that’s as good as it’s ever going to be using that method. (laughs) The album went to No. 1, and to me that was the vindication. I unlocked the door and said, “That’s it, I’m not doing it like that anymore.” And that’s a doggone good thing. From then on I started working with real people and getting out in public. It still took a little while but once I started touring in 1997 I joined the real world. I finally started having what you’d call a normal career.

What prompted the return to the Blue Ridge Rangers now?

In all those 30-something years, there wasn’t a month that went by that I didn’t think about the Blue Ridge Rangers. I was going to do it someday. I collected songs from time to time. Sometimes I’d even make a list, but this was in the age before computers so it wasn’t permanent. I’d put the list somewhere in a drawer and three years later I’d think, “Gee, where’d I put that list?” (laughs) Then [in August 2008] my wife says, “You know the Blue Ridge Rangers album you did? It’d be great if you did another one of those.” I was dumbfounded. It was like it’s a Saturday morning and your wife walks up to you with all your fishing gear, lays it in your arms and says, “Honey, why don’t you take a few days and go fishing?” (laughs) I was so surprised, and I jumped at it. I got serious about songs and who I’d like to have on the record and all that.

You’ve said that you spent much of the last few years working on improving as a guitarist. What inspired you to do that?

At about 14 I told myself, “I’m gonna grow up and be a really good guitar player like Chet Atkins.” You might say that all my life Chet was way, way up there at the top of the mountain, the embodiment of what you could do if you practiced hard enough. Then somewhere in the ’90s I got bit by the Dobro. Bear with me here. All roads Dobro lead to Jerry Douglas, and Jerry Douglas is now my favorite musician of all time. He’s at the top of my list of everyone, including Elvis Presley or James Burton or Otis Redding. Jerry Douglas is the man, in my heart. I was listening to a lot of his records just loving his great music. Then a little molecule of that memory became full recall in my brain: the 14-year-old making that promise and thinking of Chet Atkins. I had the emotion the way some people do under hypnosis, suddenly they’re there in that moment. All these years had gone by, and I hadn’t done it. I was about 48, and had the choice right then to wave it off or say, “Man, you’d better get busy.” That’s when I decided I needed to pursue my dream. This was about ’92. I became demonic. I started practicing Dobro and finger-style slide, and that evolved into my Tele playing, my finger-style guitar playing, trying to play with a pick the way the great guys do, flat-picking. It took a long, long, long, long time. But I told myself, “It’s OK. Practice everything, it doesn’t matter.” I started practicing scales, I started practicing rolls, and even though it was horrible in the present, in my mind I was that 14-year-old kid again and I could forgive myself. When you start that process, you sit there feeling pretty embarrassed that anybody can hear you. But I finally knew what the mission was. It took about 15 years, but now I’m comfortable. (laughs) I have loved being around people who can play, and being able to answer when it’s my turn and play something worthwhile. At the end of a take, Buddy Miller will say, “Well, I didn’t hurt myself too much.” He’s so self-deprecating and humble about his own ability, and of course he’s one of the most amazing musicians on this planet—but he always acts as if it’s some sort of an accident. (laughs) I hope to keep that state of mind in my own playing and continue in a frame of humility. I’ve been aiming at this all my life. It’s late coming to me—I did the hard work as an adult. So I realize what it took to do it, and that makes me more appreciative. It’s not that long ago that I was awful and I couldn’t do it. That’s still a fairly recent memory. So now I’m just happy that I can sit in with guys that can really play and, like Buddy says, not hurt myself too bad.

What’s your goal for the Blue Ridge Rangers record?

I’d love for it to sell 10 million copies and be on the top of the pop music charts like Beyoncé or Justin Timberlake or somebody. (laughs) My publicist would say, “John, don’t admit that it’s probably not going to do that.” They want you to put a smiley face on everything. Honestly, the first goal has been met: It’s really good, and I love to listen to it. It’s music that resonates with me, and it rings true. I feel very comfortable about that.

By Chris Neal

Jan/Feb 2010 Issue of M Music & Musicians

comment closed