BACK TO THE FUTURE

John Fogerty finds a new revival by letting go of the past

By Russell Hall

Twenty-five years ago, standing at the Mississippi gravesite of blues icon Robert Johnson, John Fogerty experienced an epiphany. “It just hit me that I had to perform my songs again,” Fogerty recalls. “It didn’t matter who owned them, just like it didn’t matter who owned Johnson’s. The world knows they’re mine, so I needed to sing them, before I found myself in the ground next to Robert.”

Few artists boast a catalog of songs more worthy of being showcased. The list is staggering—“Proud Mary,” “Bad Moon Rising,” “Fortunate Son,” “Up Around the Bend” and “Centerfield” skim the surface of Fogerty’s compositions. Between 1968 and 1972, as Creedence Clearwater Revival’s frontman, Fogerty was a relentlessly prolific hit-maker, penning a trove of classic rock tunes that have endured for decades. “A good songwriter is a good songwriter in any era,” he says, “but there’s something to timing. A lot of happy stars have to align for a song to become a classic.”

Fogerty’s musical journey began with the Blue Velvets, a band he formed in his hometown of El Cerrito, Calif., with his older brother Tom and pals Stu Cook and Doug Clifford. Honing their skills on the club scene, the group signed to San Francisco-based indie label Fantasy Records in 1965. Renamed the Golliwogs by a Fantasy executive, the band released a handful of forgettable singles before Fogerty rechristened the group Creedence Clearwater Revival. “I was very driven,” he says. “It was life and death. We didn’t have a publicist, we didn’t have a manager, we didn’t have a producer, and we were on the tiniest label in the world—so we had to do it all with music. And that kind of meant me.”

His first self-penned narrative song, “Porterville,” marked a breakthrough, but it was Creedence’s slinky, guitar-drenched rendition of Dale Hawkins’ “Susie Q” that opened the radio floodgates. Then, starting with “Proud Mary,” Fogerty embarked on a writing and recording tear that rivaled that of the Beatles a few years prior. Between 1969 and 1971, Creedence scored 10 unforgettable Top 20 hits, all penned by Fogerty. “I was a kid on fire,” he marvels, “and very much a part of the time in which I was creating.”

If Creedence’s rise was sudden, its fall came just as swiftly. Resentment toward Fogerty’s control and leadership—he wrote, arranged and produced all the band’s material—fostered infighting, and in 1972 the group dissolved. Meanwhile, Fogerty had become fed up with the onerous terms of his Fantasy contract. To free himself, he surrendered ownership of his existing songs to label owner Saul Zaentz. “I had an aptitude for music,” he notes, “but the business and relationship parts were woeful.”

The ensuing years became a dark time for Fogerty. After releasing a moderately successful self-titled solo album in 1975, the artist dropped out of sight. Fans were encouraged by an apparent comeback in 1985, when the Rock and Roll Hall of Famer released the multiplatinum album Centerfield. Still, a bizarre lawsuit brought by Zaentz—accusing Fogerty of self-plagiarism, a charge Fogerty successfully repudiated in court—seemed to reinforce longstanding troublesome issues. Fogerty began to tour again, although he rarely performed Creedence songs.

Fogerty’s personal tide turned following that fateful sojourn to Robert Johnson’s gravesite around 1990. As chronicled in his new memoir, Fortunate Son: My Life, My Music, Fogerty began performing his classic Creedence material soon after releasing the acclaimed 1997 album, Blue Moon Swamp. Penned on the heels of a hugely successful solo album—the star-studded 2013 record, Wrote a Song for Everyone—Fortunate Son is an unflinching, introspective examination of the ups and downs of Fogerty’s career, including his marriage to Julie in 1991, an event that figured heavily into his re-emergence.

Not surprisingly, however, Fortunate Son is often most riveting when it presents the stories behind the monumental hits. At 70, Fogerty continues to find songwriting at once challenging and rewarding. “It’s like being a runner or an athlete,” he says. “The first thing you have to do is put one foot in front of the other and know that it’s going to be slow and laborious. Things will be stupid at first, but after a while you get back into the flow. That’s when things begin to happen.” Fogerty discussed with us his memoir, his evolution as an artist, and what still makes the Creedence sound special.

Why write your autobiography now?

The impetus came from my wife, Julie. She pushed me, put energy into it. Otherwise I may not have done it for several more years. But for a long time, 10 or 15 years, I’ve had this feeling it was something I would do.

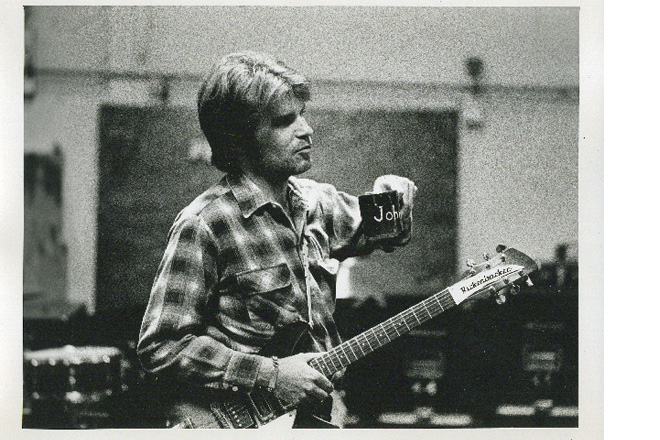

San Francisco, 1970

Was it cathartic telling your story?

I think so, but probably not in ways people might expect. Most people tend to think about my, shall we say, colorful journey through music—but I was much more struck by how deeply I love my wife. Writing about that solidified those feelings even further. The career and business stuff isn’t something I can change. I’ve long stopped festering over those troubles—although in years past I did, of course.

“Proud Mary” marked a major turning point.

That was an epiphany. I had grown up loving songs and songwriters—going back to the American Songbook era and Tin Pan Alley—because that’s what my mom knew. That was pre-rock ’n’ roll. And of course I loved all the great writers from the rock ’n’ roll era. I had been writing songs since I was about 8, but “Proud Mary” was an evolution. I thought, “Oh my goodness, look at this thing!” I knew instantly that it was a great song. It gave me tremendous confidence. There was a sense of, “John, now you’ve got to live up to this. You can no longer use the first record you made as your high-water mark.”

Were you bothered some critics didn’t think the music was cool?

It didn’t bother me at all, although it bothered the other three guys in the band. They were obsessed with the idea that we weren’t hip enough, weren’t cool—Rolling Stone didn’t recognize us, all that nonsense. First, I understood that most people who were acting cool weren’t having anywhere near the success with songs that I was having. The San Francisco bands—the psychedelic groups—were jealous, because they couldn’t do it. Plus, what I was doing was exactly what the Beatles did. All the artists I loved—Elvis, the Beatles, the Stones—were doing songs suitable for radio. And they were plenty cool enough for me.

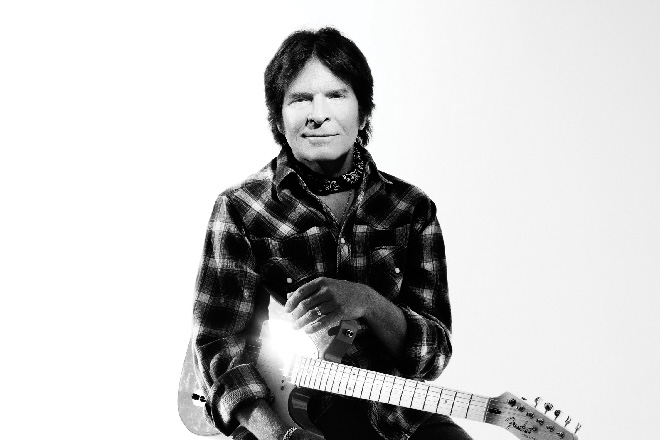

Photo Credit: Alan Silfen

Your songs often embrace a Southern vibe.

The things I gravitated toward when I was growing up—music, films, books—tended to be Southern. My mom brought my attention to people like Stephen Foster and Mark Twain. Those were people I admired. When I began to write songs that way—starting with “Porterville,” really—it seemed very familiar. It wasn’t contrived. But if someone had told me, in my middle teens, that I would somehow combine Stephen Foster and rock ’n’ roll, I would have thought they were crazy. I loved the same rock that other kids liked.

Your sound is rarely overly polished.

That’s my favorite kind of music. I tend not to like things squeaky-tight. There have been times—when I’ve worked with some session guys, for instance—when the music ended up that way, and those probably weren’t high points in my career. Anything with a groovy, funky vibe—a Booker T. and the MGs sort of thing—is the best music, as far as I’m concerned. I love that sense of swing or swagger or soul. If you make music too precise, you squeeze those things out of it.

Many songs begin with a guitar riff. Still true?

Pretty much. I’ve written a few songs at the piano. I’ve also occasionally gotten an idea and started a song before I knew what the instrumentation would be. But because I’m a guitar player—and because I grew up with great reverence for people like Duane Eddy and Scotty Moore and James Burton—somehow inventing a riff triggers the process. It’s happened over and over again. “Up Around the Bend” is a good example. I got that riff and started thinking, where can this go? A few days later I was riding my motorcycle and the phrase “up around the bend” popped into my head. It had that sense of flight, an excitement that you’re headed someplace that might be better. The riff matches the mood of that sentiment.

Bar bands can usually nail Creedence tunes. Does that please you?

I think that’s because the arrangements were well thought out. The songwriting is one thing, but what’s the band going to play? Generally a singer-songwriter sits with his or her acoustic guitar and writes the song, and then they let someone else actually make the record. Whereas my job—going back as far as I can remember—involved showing everybody what to play. It fell to me to figure out all the parts, be a good producer, and make a good record. I’ve always said, ‘Yes, the music is simple, but it’s the right simple.’ You don’t have to be a killer musician to play Creedence songs and have them sound really good. The groove is the main thing—how the music feels.

Why so few love songs?

I just didn’t understand that concept. Although I will say when I was 18 or 19, I made a conscious choice to go away from that. The records Tom and I made as teenagers—and then later as Golliwogs—had some of that. But I felt it was just words—it didn’t have real soulful intention. Especially after writing “Porterville,” I got myself to a point where I didn’t believe in that type of song. I felt that type of writing was trivial or frivolous. Later, when I decided to write a song for Julie—something authentic, something I truly feel and see as our relationship—that was important to me. I consider the song “Joy of My Life” to be my first love song, because it was truly about us.

Photo Credit: Myriam Santos

Are you surprised songs like “Fortunate Son” remain relevant?

It’s interesting. Once I decided to get away from love songs, I discovered I could write about things I felt passionate about. I was able to create an illustration. It was a matter of presenting a point of view and trying to dissect an issue as best I could within this little vignette. I tried to tackle things of that sort—social commentary. The listener certainly knew how I felt—the point of view was clear—but it wasn’t a rant. I think that’s part of the reason why, in the modern era, those songs continue to hold up.

Have a go-to guitar for songwriting?

For the past two years or so I’ve been playing an Ibanez—what some would call a shredder guitar—pretty much every day. But recently I’ve started to branch out, as I’ve gotten closer to what I’ve wanted to get out of that guitar. I’m starting to play a lot of Telecaster-style chicken-pickin’ licks on the Ibanez. It’s starting to tap me on the shoulder—tell me I need to have my Telecaster sitting there, too. That’s kind of how that works. A few years ago, when I was deep into the chicken-pickin’ thing, I was playing the Telecaster a lot.

How about for live performance?

My Gibson Goldtop with P-90s gets a lot of use, as does my Les Paul Custom. That’s the guitar for “Fortunate Son” and “Proud Mary” and “Bad Moon Rising.” It’s a great guitar, one of the few new guitars that really does the trick for me. I also play a lot of Telecaster. And I’ve got a couple of acoustics—one for “Have You Ever Seen the Rain.” I’ve been playing Taylors, but recently I had a wonderful Santa Cruz acoustic built for me. It’s a fantastic guitar. I’m doing some things right now to get it amplified properly, so the audience can hear it.

Any thoughts on the legal entanglements you endured?

Those things no longer carry the weight they once held. Finding love sort of made all of that fall away, partly because I guess I had to go through all that in order to find Julie. I would never have met her had all those other things worked out in the traditionally correct way. I wish there had been a shortcut, but because I’m so filled with love now, all the rest doesn’t matter. That’s my philosophy—the most important thing in the world is love. M

Photo Credit: Nela Köenig

comment closed