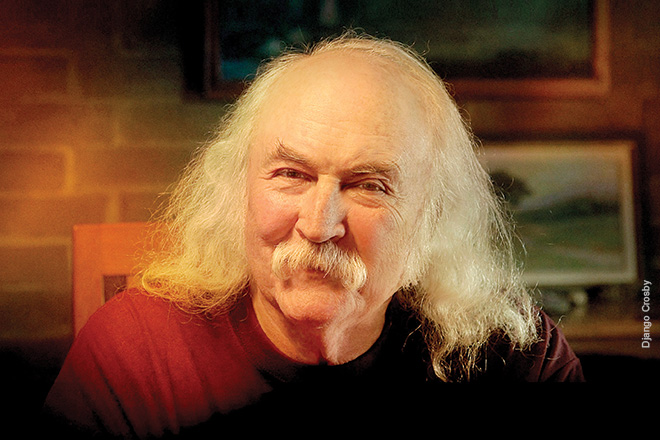

DAVID CROSBY

He helped create two iconic bands, but his latest set is a family affair

By Jeff Tamarkin

There’s always been plenty of harmony in David Crosby’s famed voice and songwriting. His life, on the other hand, not so much. He’s endured battles with drug abuse, brushes with the law, and a long line of health scares—the latest in February when he underwent an emergency heart procedure. In the ’80s, Crosby spent time in prison on drug and weapons charges, and in the decade that followed he was injured in a motorcycle accident, lost his home in an earthquake, and had a liver transplant. “My health’s not that great, but I’m very happy and I love working,” he says. “I’ve got more to say. I don’t feel that I’m done.”

Despite Crosby’s wild personal ride, musically his legacy is cemented. During a near 50-year career, the California native has accumulated multiple gold and platinum records and has been twice inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as a founding member of the Byrds and Crosby, Stills and Nash. With the occasional addition of Neil Young, CSN has recorded some of rock’s most enduring classics. The Grammy-winning group still tours annually, putting new spins on the standard formula, including gigs backed by Wynton Marsalis and the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra in NYC in 2013.

His vocals as pristine as ever, Crosby is celebrating the release of his latest album, Croz, his fourth solo effort and first solo release in 20 years. The 11-song LP was co-produced with Daniel Garcia and Crosby’s son, keyboardist James Raymond—a successful TV composer who reunited with Crosby in the late ’90s. “Almost immediately after I found out he was a musician, I gave him a set of words and found we had this incredible chemistry,” says Crosby of the son he didn’t know he had. That father-son chemistry is evident on Croz, which debuted at No. 2 on the Billboard Folk Albums chart. “We’re happy about all these songs,” says Crosby, 72. “We’re pretty stoked.”

What’s the goal behind Croz?

The songs on this album are honest. Honesty is a big deal in songs, it’s what gives them force. “If She Called,” is probably the saddest song I’ve ever written. I wrote it when I saw some hookers working outside a bar and realized that I didn’t know how they dealt with it. I didn’t understand where they hid their hearts and their souls when they’re doing that thing, which is an awful thing to do for a living. That’s a sad idea, and it’s truthful.

How does Croz compare with your solo debut, 1971’s If I Could Only Remember My Name?

A lot of people who loved that record, my solo stuff or my work in general are thinking that it’s going to be another one of those. But it’s definitely not. I hope they’re not disappointed, but I had to do what I was going to do.

Tell us about “Radio.”

That was the first song James and I wrote for the album. It’s about being able to reach out and help others. It’s couched in seaman’s terms, because the law of the sea is that you always help another sailor who is in trouble, a rule that predates any country’s laws. You get that SOS, there’s not a maybe about it—you go. I’ve been a sailor my whole life, so that’s deeply ingrained in me. It’s such a positive song that it got us excited. We started writing other stuff and at some point said, “I guess we’re making a record.” We didn’t have any money, but James has a studio in his house. And I slept on the couch.

What about “Set That Baggage Down”?

It’s a straight-up AA meetings thing: You need to put your baggage down. You have to look at what you did, you have to learn from it, and then you have to put it down. You can’t go on with your life carrying all that crap with you. That’s a basic truth.

What’s it like working with Wynton?

We [CSN] played with Wynton at Lincoln Center and it was like getting to play with the big kids. We were thrilled to be working with those guys. Wynton did me a huge favor by playing on “Holding on to Nothing.” I said, “Listen to the song and if you like it, I’d love for you to play on it. If you don’t like it, it’s OK. I don’t want you to play on something unless it grabs you and pulls you.” He loved it, and he played beautifully on it. The jazz thing is very strong in me and in James. We love complex changes.

Mark Knopfler also appears.

I have a friend who’s an Italian promoter. He said to Mark’s manager, “I think Mark and David Crosby could make good music together. Maybe they can write a song.” Mark’s manager said, “Mark doesn’t really do that. He only writes his own stuff, but he might play on something if he likes it.” So I sent him “What’s Broken,” and he played on it. He’s not just a great writer and singer, he’s a master record maker. When you start listening to that part over and over again, you notice his sense of structure and realize he’s brilliant. He makes setups and payoffs and structural stuff that are just crazy right.

You play guitar on only one song.

I play on “If She Called.” If I can get Marcus Eaton to play—who’s five levels better than I am on guitar—I will. I’m all about serving the song. My sense is that I don’t have to prove I can play. If you don’t know I can play guitar by now, you haven’t been listening. I still have a big ego, but I wasn’t trying to prove anything with this record other than I can sing.

You’ve embraced digital.

It’s totally different because we can use Logic or Pro Tools and work anywhere. You can record in the back seat of your car. James has a good studio. I happened to have a couple of the best speakers in the world that weren’t being used, so I gave them to him. We had the tools, we just didn’t have any money—that’s where the generosity of friends came in.

Your father was a cinematographer. How does film influence your music?

I see movies as the greatest art form on the planet because not only do they have their own art, but they include my art—music—and make that part of something bigger. Most movies are junk, but making a song be like a movie and have it take you on a little voyage is a cool thing to do. The song “Morning Falling” came to me as a vision of an innocent family getting wiped out in a drone strike. I’m sure I’m not going to be high up on the government’s list of their favorite artists again—like I ever have been. But that’s the truth and I wanted to speak it.

Why did the Byrds kick you out in ’67?

It had to do with me being an egotistical son of a bitch, wanting to record my songs and wanting a bigger role. We were young kids and somebody gave us millions of dollars and told us we were wonderful. That’s deadly. I’m not saying it wasn’t fun, but it doesn’t encourage sanity and restraint.

How are things with Stephen Stills?

Much better. I used to give Stephen the stink eye every time he made a mistake or sang out of tune. I was constantly at odds with him. Then I realized I care about the guy. I know he’s not perfect and I know he’s got a giant ego. I know all his good points and bad points. But I love him. I love the music he’s written. I get to sing—“And there’s a rose in a fisted glove, and the eagle flies with the dove, and if you can’t be with the one you love, love the one you’re with”—every night, and you know what? I’m grateful.

What’s vital in music?

The songs are where any piece of work needs to come from. You have to be able to sit down in front of somebody and make them feel something. I don’t care what it is—anger, triumph, sadness, longing, love, lust—if you can make people feel something with a song, then you’re doing it. You’re in the ballpark. If you can’t, you’re not. It has to be real.

comment closed