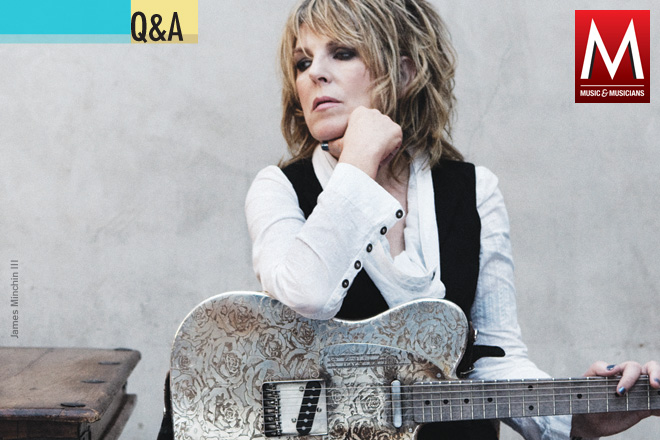

LUCINDA WILLIAMS

A songwriter known for melancholy looks on the bright side

Lucinda Williams has earned a reputation over the last three decades for writing songs that were as melancholy as they were dazzling. So, many fans were surprised when her most recent album, 2008’s Little Honey, found her sounding happy and optimistic. Her latest, the aptly titled Blessed, further proves that emotional turmoil isn’t the only fuel for her art. “Now I’m writing about things other than unrequited love,” says Williams, who wed music-biz veteran Tom Overby in 2009, “things that are more universal in nature.”

Williams began composing for the new album in May of last year, surrounding herself with notes jotted down while she was on tour. “The actual process comes in spurts,” says Williams, who typically uses her trusted 1970s Martin D-18 for writing. “It’s like I’ve been hibernating, and then once I get into that mode, I dive in.” Finding herself with enough songs to fill two albums, Williams pared down the material and hit the studio with producers Don Was, Overby and Eric Liljestrand. The results range from guitar-drenched country-rock to languid ballads tinged with Memphis-inspired soul—and there is still some darkness in the lyrics, as evidenced by the kiss-off rocker “Buttercup.” “That’s the only ‘bad boy’ song on the album,” says the Louisiana native, whose father is National Arts Award–winning poet Miller Williams. “I had one more to get out of my system.” She spoke with us from her home in Los Angeles about her new artistic direction.

How did you team with Don Was?

It was time to bring in a different element, a new set of ears. My husband, Tom, suggested we reach out to Don, and it turned out great. Don fit in perfectly with us, and Eric did the engineering. It was a very democratic process, but then again it always is when I make an album. It’s exciting to work with someone who’s made great albums that have also been commercially successful. Don understands the artistic process.

Were there surprises in the studio?

I was surprised that my vocal tracks went down so perfectly. There were no issues with pitch or anything like that. I would look through the glass at the guys, and they’d be standing there like, “Wow!” I think that came from feeling comfortable with Don, and from Eric’s talents. But I also feel my voice is better than it’s ever been. Right from the start Don said he wanted to build everything around the vocals, and of course I said yes. I don’t like it when vocals get buried in the mix.

How did you approach the writing?

I grew up listening to Bob Dylan’s songs, which were so majestic and so topical. I always wanted to write songs like “Masters of War” or “The Times They Are A-Changin.’” This album was an exercise in writing those types of songs. They grew out of what was going on in my life, what was in the news or what sort of music I was listening to. I never sit and think, “This record is going to be about this topic.” I take a very organic approach. Of course at the end of the day you want to include the songs that work best together, and the ones that sound the best.

What is your process like?

I’m always observing, thinking and jotting things down. At one point in my life I used to worry, because I would go through long stretches where I wouldn’t finish a song. But over time I realized that I just had a routine that was particular to me. I would come up with plenty of songs, but they always came in a flurry. I might not finish anything again for another six months or so. But I’m more prolific now than I’ve ever been. That started sometime after my mother’s death [in 2004], which seemed to propel me in some way. When I was writing the songs for West [2007] I just kept going and going. That happened with this album as well.

Do your broad musical tastes come from growing up in the 1960s?

Absolutely. The artists I listened to mixed all different sorts of styles. The Band is a good example, as are Bob Dylan, Neil Young and Creedence Clearwater Revival. They all did country, folk-rock, rock—all sort of things. Whereas when I was first coming up as an artist in the ’80s, I fell in the cracks between country and rock. I was told I was too “country” for rock, and too “rock” for country. To me the important thing has always been the song itself, not the style of the song.

Do ballads come easier than rockers?

Yes. That also happens by default because I always write on acoustic guitar, but the fast-tempo songs are more challenging. I wish I could write more like Neil Young: (sings) “Keep on rockin’ in the free world!” But then again, a lot of those songs may have started out as ballads. If you take a song like “Rockin’ in the Free World” and slow it down, it almost becomes a folk song. A lot of it has to do with what happens in the studio. I make demo tapes for all the guys to listen to before we record. Depending on what happens in the studio, a song might become a rocker. That’s the fun part of the process, the part where you’re deciding what to add or what tempo you want.

Why do you like your Martin D-18?

It’s got a special vibe and I have an emotional attachment to it. It’s sitting here beside me on its guitar stand. I’ve written so many songs on this guitar. I’ve had it since 1979. I was living in Houston and bought it for $400. I used to play it on stage, but it was always feeding back. I still take it on the road in order to write.

What do you play on stage these days?

A Gibson J-45, the Everly Brothers model. It’s a great guitar as well.

Did your father give you any advice?

Don’t censor yourself, that’s one. The other thing was the importance of economy in writing, the importance of making every word count. Something might initially come as a big flurry of words and ideas, but you have to sift through that and trim the fat. He also taught me not to fall back on clichés—“moon in June,” “stars in your eyes,” those sorts of phrases. There’s just a handful of big themes—love, death, sex—but it’s important to address those topics in original ways. One way to do that is to tell a story.

How about advice from friends?

Emmylou Harris and I were in Nashville going out to dinner with some people, and there was a woman singing live opera in the restaurant. I turned to Emmylou and said, “I wish I had a range like that, I wish that I could do more with my voice.” She immediately said, “Your limitations are your strengths. Your strengths come from learning how to work within your limitations.” That really stuck with me. I think that’s one reason I’m a stronger singer today. I’ve learned how to use my voice in the best possible way.

–Russell Hall

comment closed