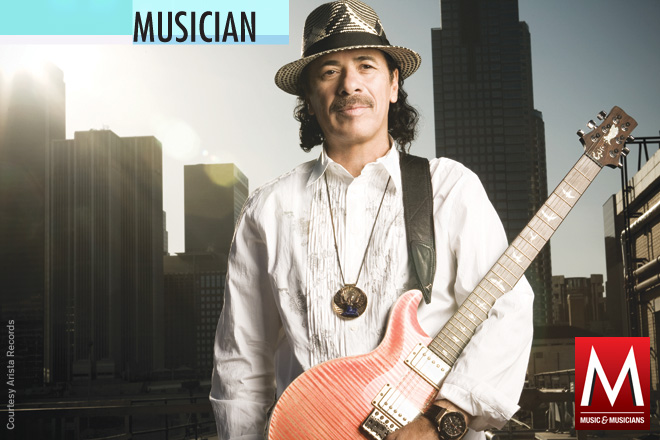

CARLOS SANTANA

An iconic guitarist wholeheartedly embraces a past he helped to create

By Jeff Tamarkin

A few months ago, Carlos Santana walked on stage at the Bethel Woods Center for the Arts in New York—a modern venue built on the site of 1969’s fabled Woodstock festival—and wasted no time delivering his audience a chill-inducing moment. He opened the concert with “Soul Sacrifice,” the same combustible jam that launched him into the rock pantheon when the version he played at Woodstock was seen in the titular documentary about the festival. When the song was over, Santana said only three words: “We meet again.”

“It made me feel really grateful that that was ’69 and I’m here now, and the band is stronger than ever,” he says of his return to that hallowed rock ’n’ roll ground. “A lot of musicians didn’t make it. I closed my eyes and I could hear the roar of the crowd through Jimi Hendrix and Sly [Stone] and the Who and, of course, us. It made me feel really grateful that I was at ground zero of peace and love again.”

Like that appearance, Santana’s new album, Guitar Heaven: The Greatest Guitar Classics of All Time, consciously blends the past with the present. It finds the veteran guitarist, his current band and a roster of guest singers covering a baker’s dozen tunes from the heyday of classic rock. The new album’s all-star collaborations were the brainchild of veteran music business executive Clive Davis, who also guided Santana’s 15-times-platinum Supernatural. “Clive matched the singer with the song,” Santana says. “He’s a visionary.” Among his choices were Rob Thomas, who sang on Santana’s chart-topping “Smooth” in 1999 and returns to lend his pipes

to Cream’s “Sunshine of Your Love”; rapper Nas, who transforms AC/DC’s “Back in Black”; and rocker Chris Daughtry, who tears into Def Leppard’s “Photograph.” Santana—who recently became engaged to drummer Cindy Blackman—spoke to us about his new album, his storied history and how he has survived the fickle music industry for more than four decades.

How did you approach these songs?

Making anything sound like Santana is really adding colors and textures and rhythms from Africa. People give me too much credit, but all I do is make it more African and more Caribbean. I’m often asked, “Did you listen to the original and try to copy the wah-wah, the fuzz and the amplifiers? Were you meticulous about copying the sound?” No, I did completely the opposite.

What holds the songs together?

The main essence that glues this thing together was trust. It took Clive to trust me to do it, and then it took me to have trust in him. And then it took both of us to have trust in the producers, Howard Benson and Matt Serletic. It took them to back off when we got to the studio, and give me the first hour with my band because it is my band playing on every song. We graciously extended an invitation to the greatest singers of the day, and they brought their spirit and their heart. Yet they had to come up with a serious game, a positive game, because the band plays so well. They had to measure up. It was challenging for them, but challenging is good because it takes you outside of complacency.

Can you feel truly close to a cover?

Whether it’s George Gershwin or the Beatles or anything, when you hug someone you hug them full-on. That eliminates any distance. It doesn’t matter who wrote it if you eliminate the distance between your heart and the song. The way Miles Davis played “Summertime”–which George Gershwin wrote—when you hear it, it sounds like Miles Davis.

Why does the idea of hosting guest artists appeal to you?

I’ve been doing that since 1967, with Olatunji or Michael Bloomfield. It’s not a shtick or a gimmick for me. People think, “Oh, Santana’s gonna wear it out, inviting so many people to his albums.” But I’m on this planet and I’m playing for people. Everything is a conscious decision. I made a conscious decision to get away from radio from 1973 to ’99. But when I had children, they wouldn’t hear our music on the radio unless it was oldies-but-goodies, so we hooked up with Clive and before I knew it everybody wanted to play with me. Supernatural was a win-win for people on the planet and accountants, lawyers, the IRS—everybody! The main thing is focusing on soulful, heartfelt service.

How has your approach to the guitar evolved over the years?

I used to look at my guitar like it was building blocks, creating with a hammer and nails and learning how to do something. I don’t look at it like that anymore. It’s more like drinking water. Water is going into your system and then you’re gonna sweat it out. You trust your fingers, you trust your heart, you trust that you’re going to say something soulful and significant.

How do you relate to your band?

Certain artists use their musicians as a backdrop for themselves. I do the opposite. I expect the musicians I’m surrounded by to attack ferociously—all of them, at the same time sometimes. When you see Santana, it’s like seeing a three-ring circus with lions, elephants and tigers and they’re all hungry and want to be fed. It’s not just the ringmaster.

What are some of your fondest memories of Santana’s early days?

All of us were on a quest of self-discovery. Some would only discover certain things and that’s all they would want to learn. I didn’t want to be stuck with anything. I just love life and music. Some people get a Ph.D. to be a doctor of the toe; they only want to know about the toe. I need to know the whole body: the eye, the ear, the heart, the lung and the fingers. The message from the ’60s was consciousness revolution. All those songs were probably conceived with … I’m not going to call it drugs, because that would be demeaning, but I will say some mind-expanding medicine. There’s a difference. Humans make drugs in a laboratory. Mother Nature makes medicine from the ground. The sun tells the plant what color, what texture, what aroma, what flavor to be, and when it dries and you make tea out of it, this plant knows where to go throughout your body. It’s amazing that everything knows what to do and why. That’s how music should be, like a beam of light, with some earthy notes.

You were once a disciple of Indian philosopher Sri Chinmoy. How did his teachings affect you?

It affected me a lot, because I got higher than from anything I was taking back then. So I quit smoking pot from 1972 to ’81. It was kind of like a boot camp. It was very disciplined. Get up a certain time every morning and meditate, only eat certain foods, read books that keep your consciousness from being vulgar or gross. I don’t regret it. It still gives me an extra wind. Whenever I feel my body is trying to convince me that I’m tired, I change the way I breathe, change the way I think and I get another pocket of air and find another gear. I tell you, most people who are 63 walk like they’re ready for the home. They don’t sound or look the way I do.

Who is your favorite guitarist ever?

Jimi Hendrix. He understood the whole spectrum of sound as a visual thing. When he came along, it was almost like the difference between eight-millimeter film and CinemaScope surround sound in 3-D. There are certain people on this planet you recognize as having a supreme standard of excellence. But to be like that, you have to put in the discipline. Jimi Hendrix went to the bathroom with the guitar on. When he was eating and cooking and ironing, he wouldn’t let go of the guitar. The guitar becomes like your lungs—you don’t even think about it. If you have to think about it, there’s already distance. The music should just flow.

comment closed